Page controls

Page content

Introduction

Children with unaddressed reading difficulties have not failed the system; the system has failed them. We now know that this is not inevitable, even for children who face significant challenges.

- Ontario 2003 Expert Panel on Early Reading Report at p 7

Science has shown that there are effective and ineffective ways to teach word reading. Reading scientists have studied how young children learn to read for decades. This body of scientific research, also known as the science of reading, has outlined how reading develops, why many students have difficulties learning to read, and how to teach early reading to prevent reading failure, among other things.

|

The science of reading This report uses terms like the “science of reading,” “reading science,” “research-based,” “evidence-based” and “science-based” to refer to the vast body of scientific research that has studied how reading skills develop and how to ensure the highest degree of success in teaching all children to read. The science of reading includes results from thousands of peer-reviewed studies and meta-analyses that use rigorous scientific methods. The science of reading is based on expertise from many fields including education, special education, developmental psychology, educational psychology, cognitive science and more. |

Although some approaches to reading are promoted as “research-based,” this research does not always follow good scientific methods.[645] Many approaches are based on theories or philosophies with no scientific evidence to support them. In contrast, the science of reading includes results from thousands of peer-reviewed studies that use rigorous scientific methods.[646]

Learning to read is a complex process. For most children, learning to read words does not come easily or naturally from exposure to language or reading. Reading is a skill that must be taught.[647] Ontario’s 2003 Expert Panel on Early Reading noted: “Children must be taught to understand, interpret, and manipulate the printed symbols of written language. This is an essential task of the first few years of school.”[648] These experts also noted that there is a critical window of opportunity, and age four to seven is the best time to teach children to read.[649]

Written language is a code that represents our spoken language. The goal of reading is to understand what we read. One important part of this is learning to decipher or “crack the code” – to become accurate and efficient at reading written words. To do this, students need direct and systematic instruction in the code of a written language (also called the orthography). Teaching the foundational skills of decoding and spelling written words in a direct and systematic way is also known as structured literacy. Structured literacy incorporates the findings from science on how to best teach foundational word-reading skills in the classroom, so that all children learn to read.

Reading science does not support approaches that rely on teaching children to read words using discovery and inquiry-based learning such as cueing systems. Many children fail to learn to read when these approaches are used in classrooms. These are consistent with a whole language philosophy, and are used in the current Ontario Curriculum, Language, Grades 1–8, 2006 (Ontario Language curriculum) and the balanced literacy or comprehensive balanced literacy approaches practiced in Ontario school boards.

The three-cueing instructional approach outlined in the Ontario Language curriculum teaches students to use strategies to predict words based on context cues from pictures and text meaning, sentences and letters. As well, balanced literacy proposes that immersing students in spoken and written language will build foundational reading skills – but significant research has not shown this to be effective for learning to read words accurately and efficiently. In these approaches, teachers “gradually release responsibility” from modelling reading texts or books, to shared reading with students, to guiding students’ text reading, to students’ independent text reading. These approaches are not consistent with effective instruction as outlined in the scientific research on reading instruction.

The inquiry examined whether the current Ontario curriculum and school board approaches to teaching reading reflect evidence-based approaches and are supported by rigorous scientific research. It found that overall, the way that early reading is taught in Ontario is not consistent with the science of reading. Although a few boards have made some attempts to incorporate isolated aspects of effective early word reading instruction, these approaches are piecemeal and do not meet the criteria supported by the science of reading.

The Ontario curriculum is based on the ineffective three-cueing ideology and instructional approach. Balanced and comprehensive balanced literacy are pedagogical approaches that are aligned with a whole language approach to teaching reading. These methods are ineffective for a significant proportion of students, many of whom are members of Code-protected groups, and may harm students who are at risk for failing to learn how to read.

The inquiry also reviewed the training teachers receive through Ontario’s 13 English-language public faculties of education (faculties). It found that teacher education programs for future teachers (also known as pre-service teachers or teacher candidates) and Additional Qualification (AQ) professional development courses for current teachers (also known as in-service teachers) do not prepare teachers to use approaches to teaching word-reading skills supported by scientific research on effective classroom instruction.

Future and current teachers looking to upgrade their qualifications by taking AQ courses offered by faculties in reading and special education receive little exposure to or learning about direct and systematic instruction in foundational reading skills (also called structured literacy). They are generally not taught how skilled reading develops, including the importance of strong early word-reading skills for future reading fluency and reading comprehension. They do not adequately learn how to provide instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding, word-reading efficiency and morphology. Instead, they mostly learn about the ineffective approaches for teaching reading skills in the Ontario Language curriculum. It is not surprising then that many teachers told the inquiry they do not feel prepared to teach reading, particularly to students who do not catch on to reading quickly or have reading difficulties.

Ontario’s high rates of reading failure are well beyond the number of students who could be expected to have reading disabilities, and show that prevalent approaches to teaching reading are not working for far too many students. Ontario’s failure to use science-based approaches to teach reading and respond to reading difficulties are causing far too many children to not learn this critical life skill. This puts these students at risk for lifelong hardships associated with not being able to read. It can result in discrimination under the Ontario Human Rights Code.

Despite the overwhelming body of evidence, reading experts have noted there has been strong, deeply rooted resistance to change in the education field.[650] The inquiry found there is strong resistance in Ontario as well.

Most of the inquiry boards are not aware they are using many ineffective approaches to teach reading. Even where boards recognize the need for more science-based instruction, their ability to implement it is hampered in several important respects. For example:

- With a few small exceptions, teachers educated in Ontario English-language public faculties have not been taught evidence-based approaches to teach early reading

- Teachers are required to follow the Ontario curriculum, which is inconsistent with evidence-based approaches. Teachers cannot reconcile two irreconcilable approaches to teaching reading

- Boards and teachers have not been given sufficient guidance on how to implement evidence-based instruction in the classroom. They must determine on their own what programs, approaches and materials are best and how they can implement them

- Boards must do their own research and find the funds necessary to implement these programs

- There is strong resistance to change and strongly held beliefs supporting whole language philosophies in parts of the education sector

- Boards are finding it challenging to conduct the necessary professional development related to literacy instruction. This expertise is often not found within a board.

The basic components of effective reading instruction are the same whether the language of instruction is English or French.[651] However, depending on the community they live in, students learning to read in French may have limited exposure to the French language outside of the classroom. School may be the only place they are exposed to French in a meaningful and consistent way. It is also a challenge to find French reading resources and private supports.[652] It is critically important that schools deliver effective reading instruction in French, both to ensure students learning in French can learn to read and to support Francophone students’ French-language education rights under section 23 of the Charter.

The science of reading: evidence-based curriculum and instruction

Several key reports synthesize the large body of scientific research on how children learn to read and the most effective instructional approaches: the National Reading Panel Report in the United States; the Ontario Expert Panel Report on Early Reading; the Rose Reports in England; and the Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network Report. These influential reports all endorse systematically teaching the foundational skills that will lead to efficient word reading: phonemic awareness, phonics to teach grapheme to phoneme relationships[653] and using these to decode and spell words and meaningful parts of words (morphemes), and practice with reading words in stories to build word-reading accuracy and speed.

National Reading Panel

In 1997, the United States Congress asked the Director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to work with the U.S. Department of Education to create a National Reading Panel.[654] The panel included 14 people of different backgrounds, including leading scientists in reading research, representatives of faculties of education, reading teachers, educational administrators and parents.[655] The panel was asked to review all available research on how children learn to read and reading instruction (over 100,000 reading studies) and determine the most effective, evidence-based methods for teaching children to read. The panel also held public hearings.[656]

The panel released a report in 2000, Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction.[657] This report identified these key aspects of effective reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, reading fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension. It also stressed the importance of teacher preparation and using computer technology.

The panel’s analysis made it clear that the best approach to reading instruction incorporates:[658]

- Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. There are about 44 phonemes in the English language and 36 phonemes in French. Phonemic awareness is a foundation that supports children learning to read and spell. The panel found that children who learned to read through instruction that included focused phonemic awareness instruction improved their reading skills more than children who learned without attention to phonemic awareness. The panel also found that approaches were most effective for teaching reading and spelling when they moved quickly from oral phonemic awareness into teaching children to blend sounds and segment words while using the corresponding letters.

- Explicit and systematic phonics instruction. Phonics encompasses teaching the relationships between phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (the printed letter(s) that represent a sound), and how to use these to read and spell words (for example, blending to “sound out” and read words, and segmenting words to spell out each sound in a word). Systematic instruction starts with the easiest grapheme-phoneme associations and teaches using these to read words (to link the written form of the work with its pronunciation and meaning), and progresses to more complex orthographic patterns in words. Most phonics approaches include teaching simple and frequent affixes (a set of letters generally added to the beginning or end of a root word to modify its meaning, such as a prefix or suffix) relatively early in the process (for example, ed, s/es, ing). The panel found that explicit phonics instruction, starting in Kindergarten, results in significant benefits for young students and for older students who have not developed efficient word-reading skills.

- Teaching methods to improve fluency. Fluency is reading texts accurately and at a good rate compared to same-age peers, as well as with appropriate expression when reading aloud. Word reading efficiency is an important part of fluency. The panel concluded that along with effective word reading instruction, repeated oral reading of texts, with corrective feedback, increased students’ reading fluency.

- Teaching vocabulary. Vocabulary refers to knowing what individual words mean. The panel found that intentional vocabulary instruction and supported opportunities to use and understand the new vocabulary in the classroom are important.

- Teaching strategies for reading comprehension. Reading comprehension strategies are cognitive procedures that a reader uses to increase their understanding of a text. The panel found teaching cognitive strategies to be an effective component of reading comprehension instruction.

These elements have been termed the Five Big Ideas in Beginning Reading or The Five Pillars of Reading Instruction.[659]

Expert panel on early reading in Ontario

In June 2002, the Ontario Ministry of Education (Ministry) convened an expert panel to study reading in Ontario. The panel’s goal was to identify ways to raise the level of reading achievement in Ontario classrooms.[660]

Then-Minister of Education and Deputy Premier Elizabeth Witmer said that the government at that time had established this panel of education experts to determine the core knowledge and teaching practices that are required to teach reading and specifically referenced research-informed instructional practices and phonemic awareness:

Teachers and principals will soon gain the benefit of additional tools and strategies. For example, as part of the implementation of the early reading strategy and the early math strategy, teachers will receive resources and training in a wide range of research-informed instructional techniques. This will include how to create and enhance children's [phonemic] awareness.[661] [Emphasis added.]

The expert panel was made up of teachers, consultants, principals, school board administrators, academics and researchers from English, French, and First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities. In 2003, the panel released its report, Early Reading Strategy: The Report of the Expert Panel on Early Reading in Ontario (the Ontario Expert Panel Report).

The Ontario Expert Panel Report contains a comprehensive discussion of the important elements of reading instruction that are necessary for all students, regardless of their gender, background or special learning needs.[662] It noted that reading instruction must be evidence-based and that there is a clear consensus in the scientific community about how to teach reading in a way that prevents reading failure:

Despite the widely different conclusions and practices advocated by individual research papers or particular programs, there is an important consensus in the scientific community about the teaching of reading. Good research informs educators about the components of an effective reading program. The research is clear in showing that effective reading instruction compensates for risk factors that might otherwise prevent children from becoming successful readers.[663] [Emphasis added.]

The panel also addressed common myths associated with learning to read, including some ideas that are prevalent in whole language approaches:

Although some children learn to read at an early age with little formal instruction, it is a fallacy to assume that this happens simply because they have been exposed to “good quality” books. Most children require explicit, planned instruction – as well as plenty of exposure to suitable books – to crack the complex code of written language and become as fluent in reading as in speaking.

Consistent with the evidence, the expert panel confirmed the importance of teaching phonemic awareness and letter sound knowledge as foundational reading skills. It stated: “The evidence also shows that phonemic awareness can be taught and that the teacher’s role in the development of phonemic awareness is essential for most children.”[664]

The expert panel also addressed the importance of teaching letter-sound relationships and phonics:

…it is important that children receive systematic and explicit instruction about correspondences between the speech sounds and individual letters and groups of letters. Phonics instruction teaches children the relationships between the letters (graphemes) of written language and the individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language. Research has shown that systematic and explicit phonics instruction is the most effective way to develop children’s ability to identify words in print.[665] [Emphasis added.]

The Ontario Expert Panel Report stated that teachers’ instruction in letter-sound relationships and how to use these to read words should be planned and sequential so that children have time to learn, practice and master them.[666]

The expert panel also identified other important skills needed for reading, including oral language skills, enhancing vocabulary, and understanding the meaning of phrases and sentences. Efficient word-reading is one critical aspect of reading skill.

Ontario’s own expert panel did not promote the use of cueing systems or balanced literacy approaches to teach word-reading skills. As discussed later, the panel’s recommendations were not incorporated into Ontario’s 2006 Language curriculum or the Ministry’s Guide to Effective Reading Instruction: Kindergarten to Grade 3 (2003).

Rose Reports

In 2005, the Secretary of State for Education in the United Kingdom (U.K.) commissioned Sir Jim Rose to conduct an independent review of best practices for teaching early reading and meeting the needs of children with literacy difficulties (especially dyslexia). The 2006 Independent Review of Teaching Early Reading interim report and final report in 2009, also known as the Rose Reports, state that the Simple View of Reading is a good framework for considering the necessary component skills to target in reading instruction. The Simple View of Reading is a model of reading that has been supported and validated by many research studies. It says that reading comprehension has two components: word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension. Together, skills in these two components are “essential for learning to read and for understanding what is read.”[667]

The Simple View of Reading and the research that has supported it emphasize that strong reading comprehension requires the ability to read words accurately and quickly. Decoding includes being able to sound out words using phonics knowledge, and to recognize familiar words quickly.

In reading acquisition, early decoding based on letter-sound associations leads to fast and accurate reading of familiar and unfamiliar words, whether they are presented in context or in isolation. For example, a student with strong decoding skills can read familiar words quickly, can sound out unfamiliar words in a list of unrelated words, and can even sound out non-words (such as lund or pimet). This decoding process leads to building up immediate recognition for most words students encounter in texts. Conversely, not being able to decode negatively affects a student’s ability to read printed words accurately and to build up rapid recognition for most words. This in turn impairs a student’s reading comprehension.

Dr. Louisa Moats, an expert on science-based reading instruction and teacher education, explains:

…reading and language arts instruction must include deliberate, systematic, and explicit teaching of [written] word recognition and must develop students’ subject-matter knowledge, vocabulary, sentence comprehension, and familiarity with the language in written texts.[668]

Although the full range of skills, knowledge and pedagogical approaches that are encompassed within a complete language curriculum are beyond the scope of this report, the importance of critical instruction to build word-reading skills cannot be overemphasized.

The Rose Reports recommended that England replace the “searchlight” model of teaching reading, a model based on cueing strategies like Ontario’s current Language curriculum, with high-quality, direct and systematic phonics instruction starting by age five. The reports said that pre-reading activities should be introduced earlier to prepare students for phonics instruction. High-quality, systematic phonics work means teaching beginner readers:

- Grapheme/phoneme (letter/sound) correspondences (the alphabetic principle) in a clearly defined, incremental sequence

- To apply the skill of blending (synthesising) phonemes in order as they sound out each grapheme

- To segment words into their constituent phonemes to spell out the graphemes that represent those phonemes.[669]

The Rose Reports concluded that high-quality phonics work should be the primary instructional approach for teaching children to read and write words. High-quality phonics teaching allows students to learn the crucial skills of word reading. Once they master this, they can read fluently and automatically, which allows them to focus on the meaning of the text.

The Rose Reports offer many strategies for phonics instruction, such as incorporating writing the letters and spelling in phonics work, and manipulating letters and their corresponding phonemes within words. The reports also provide advice on the sequence of teaching phonics skills, and the pace of instruction.

Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network Report

In 2008, the Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network produced a report, Foundations for Literacy: An Evidence-based Toolkit for the Effective Reading and Writing Teacher.[670] The components of the report focused on science-based information for teachers on language and reading acquisition, and on science-based instructional methods for critical components of reading and writing. The report identified these essential components:

For reading:

- Print awareness: understanding that print represents words that have meaning and are related to spoken language

- Phonological and phonemic awareness

- Alphabetic knowledge (knowledge of letter names, shapes and letter-sound associations), phonics and word reading

- Vocabulary

- Reading comprehension.

For writing:

- Spelling

- Handwriting

- Composition.

This report provided detailed guidance on the important elements of effective instruction, including for “special populations” such as multilingual students who are learning the language of instruction at the same time as they are learning the curriculum (also referred to in the Ontario education system as English language learners or ELL students), learners from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, students in French Immersion and, importantly, students with reading disabilities, particularly in word reading/dyslexia. The report noted that “structured, systematic, and explicit teaching, with structured practice and immediate, corrective feedback is important in teaching all students, and is especially important in teaching students with dyslexia…” The report also said: “regardless of the child’s starting point, all students can benefit from high-quality instruction focused on phonics.”[671]

Models that help explain how children learn to read

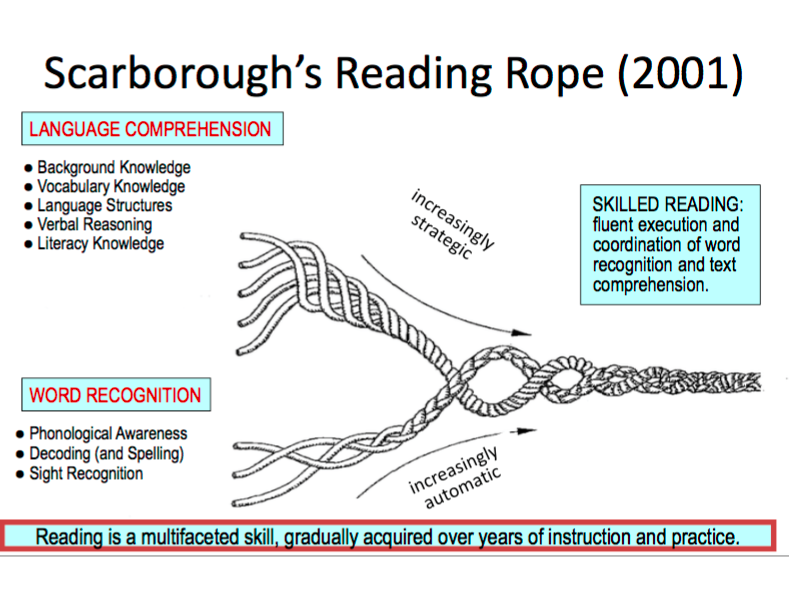

Scarborough’s rope model[672] is a science-based framework that breaks down the two major components in the Simple View of Reading, explaining how word-reading skills and oral language comprehension each contribute to reading comprehension. Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a psychologist, literacy expert and leading researcher in reading acquisition, compared skilled reading to the strands of a rope, with each strand representing a separate skill. The strands are woven together as readers become more skilled. If there is a weakness in any strand or skill, the rope will be weaker. The two major strands are word recognition and language comprehension (the ability to get meaning from words, sentences and texts at a listening level).[673] The sub-strands of word recognition include phonological awareness, decoding and spelling, and recognizing familiar words “by sight” (quickly and effortlessly or automatically). The goal of word-reading instruction is that with increasing skill development, children come to recognize almost all words by sight (the written word becomes linked in memory to its pronunciation and meaning). In this way, knowledge of spoken words and their meanings is linked to learning word forms and supports students’ decoding of words that have not yet become sight words.

Figure 2

Dr. Linnea Ehri’s Phase Theory of Learning to Read Words[674] is a useful model that explains the developmental process of learning to read words accurately and efficiently, and is supported by an abundance of research. Dr. Ehri, an educational psychologist and leading researcher on reading acquisition processes, identified four phases representing the connections between the written letters that form words and spoken words that developing readers gain as they move from novice to skilled readers:

- Pre-alphabetic phase: students read words by memorizing their visual features or guessing words from their context

- Partial-alphabetic phase: students recognize some letters of the alphabet and can use them together with context to remember (a few) words by sight

- Full-alphabetic phase: readers possess extensive working knowledge of the graphophonemic system, and they can use this knowledge to fully analyze the connections between graphemes and phonemes in words. They can decode unfamiliar words and store fully analyzed sight words in memory

- Consolidated-alphabetic phase: students consolidate their knowledge of grapheme-phoneme relationships into larger units that recur in different words.

This model explains how reading proficiency needs to develop. Preschoolers and very young students start off reading some very common words from memory (such as STOP on the stop sign), but then begin to use the grapheme-phoneme knowledge they have learned to decode words, at first letter by letter, but then more efficiently by connecting complete graphemes and phonemes and larger letter patterns (such as rimes and syllables). Students then progress to efficient reading, when they can recognize many words and large chunks of words (orthographic patterns and morphemes) automatically – known as reading words by sight or from memory. Dr. Ehri explains:

The evidence shows that words are read from memory when graphemes are connected to phonemes. This bonds spellings of individual words to their pronunciations along with their meanings in memory. Readers must know grapheme–phoneme relations and have decoding skill to form connections, and must read words in text to associate spellings with meanings.[675]

This model can help teachers understand where their students are starting from, and the types of knowledge and skills students need for their word-reading skills to develop.

In these models, the orthographic representation of a word (in other words, its spelling) becomes integrated in memory with both the word’s pronunciation and meaning. Teaching phonics is integrated with accessing the meanings of the words the students are learning to read from the beginning, and continues through to reading words with more complex orthographic patterns and with more than one syllable and/or morpheme. Researchers have noted: “The Simple View is consistent with Perfetti’s (2007) lexical quality hypothesis, where acquiring and integrating information about both word form and meaning are necessary for on-line reading comprehension.”[676]

Summary of reports and models

These influential reports and models, which are based on a substantial body of scientific research, all confirm that a critical focus of early reading instruction must be on skills that will lead to efficient word-reading: that is, teaching phonemic awareness skills, the links between phonemes and graphemes, and how to use this knowledge in decoding/reading (and spelling) words (explicit phonics instruction). They all conclude that teaching students these skills in a direct and systematic way is a critical and necessary component of teaching them to read.[677]

The science of reading shows that contrary to whole language beliefs, strong language comprehension does not lead to good reading comprehension without well-developed word-reading skills. Poorly developed word-reading skills act like a bottleneck for comprehension. On the other hand, the better a reader’s word recognition skills, the more attention they can put towards making meaning to understand texts.[678]

There are additional, critical components in a full reading instruction program. For example, effective vocabulary instruction is especially important for students with language disabilities or from less advantaged backgrounds.[679] Research in Canada and the U.S. shows that effective vocabulary instruction in Kindergarten to Grade 6 may be lacking.[680] Research studies have helped identify instructional approaches to support students in gaining the vocabulary knowledge needed to make expected yearly gains in reading comprehension.[681] Similarly, students need explicit instruction in text structures (genres), reading comprehension strategies, and the knowledge base of different domains to support reading comprehension. Also, motivating and culturally responsive instruction and texts need to be incorporated.[682] Although outside of the scope of this report, the body of research known as the science of reading addresses these many components of classroom language and reading instruction. A complete reading program requires evidence-based instruction in each area to more fully address inequities in reading achievement across Kindergarten to Grade 12.

Universal Design for Learning and Response to Intervention

Experts agree that directly teaching the specific foundational reading skills described above saves most children who come to school at risk for failing to learn to read well:[683]

…classroom teaching itself, when it includes a range of research-based components and practices, can prevent and mitigate reading difficulty…informed classroom instruction…beginning in kindergarten enhances success for all but a very small percentage of students with learning disabilities or severe dyslexia.[684]

Direct and systematic teaching of the skills that are good for all students, and essential for students at risk, is consistent with Universal Design for Learning (UDL), an educational approach that emphasizes designing curriculum and instruction to make it effective and accessible for all students.[685] The goal of UDL is to give all students an equal opportunity to learn and succeed. By using evidence-based approaches that teach the necessary foundational reading skills in sequence from easiest to most difficult, with simultaneous differentiation for learners who need more focused and highly scaffolded instruction, almost all children can gain the knowledge and skills that are being taught. That is, it allows almost all children to learn to read words in text accurately and efficiently.

In its submission to the inquiry, the Ontario Association of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists emphasized that students with typical development as well as students with reading disabilities, intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder and hearing disabilities all benefit from instruction that builds skills for decoding words and language comprehension (as set out in the Simple View of Reading).

A tiered approach to instruction, coupled with universal screening or assessment and early intervention also reflects principles of UDL.[686] Response to Intervention (RTI) or Multi-tier Systems of Supports (MTSS) are frameworks for delivering inclusive education that use UDL, and can be effective for addressing the challenges of teaching reading.[687] In an RTI/MTSS framework, students receive increasing levels of support according to their needs, but always using high-quality classroom instruction and interventions consistent with the scientific research. Many such frameworks have three tiers, and critical to each tier is reading instruction based on evidence.

Tier 1 is considered the key component of a tiered approach. At tier 1, all students receive high-quality classroom instruction using an evidence-based, scientifically researched core curriculum. Teachers must have sufficient and ongoing professional development to deliver the tier 1 core instructional program in the way it was designed.[688] An important feature of tier 1 is that all students are screened to see if they are responding to instruction as expected (gaining the required skills and knowledge). This universal early screening means students are identified and receive the programming they need before they start to experience significant difficulties. When evidence-based word-reading instruction is delivered properly, tier 1 meets the needs of most students (estimates are about 80 to 90%).[689]

At tier 2, students whose skills and knowledge are not progressing adequately to meet expectations with only tier 1 science-based instruction, receive additional instruction or intervention in small groups. These are about 15 to 20% of students who are not at the expected levels, as identified through an evidence-based screening/assessment process, and are at risk for failing to learn to read well. While continuing to receive high-quality tier 1 instruction, these students receive tier 2 support in smaller groups with increased intensity (daily instructional time, explicitness and scaffolding of instruction, supported practice and cumulative review). Evidence-based tier 2 interventions in Kindergarten and Grade 1 will be most effective for the most students.

Tier 3 supports are intended for the very small percentage of students whose reading skills do not come into the expected range with tier 1 and tier 2 instruction. These students are at high risk for failing to learn to read, or have already experienced time in the classroom without being able to meet the reading demands. Intervention at this level means smaller groups or individual interventions of increased intensity (more time, more explicit and scaffolded, with ample supported practice to master skills).

The Association of Psychology Leaders in Ontario Schools’ inquiry submission emphasized the importance of strong RTI/MTSS approaches, noting: “a combination of effective classroom instruction and targeted small group instruction has the potential to meet the needs of 98% of struggling readers.”[690]

With appropriate instruction, multilingual students (referred to in the education system as English language learners or ELL students) can learn phonological awareness and decoding skills in English as quickly as students who speak English as a first language.[691] The specific difficulties that English language learners may face are fairly predictable and can be addressed with proactive teaching that focuses on potentially problematic sounds and letter combinations.[692] English language learners will also need instruction in other aspects to fully address reading comprehension and written language.[693]As described by Dr. Esther Geva, an Ontario psychologists with expertise in culturally and linguistically diverse children, and her colleagues:

Instruction for [English language learners] should be comprehensive and include instruction in the core areas of reading (phonological awareness, phonics, word level fluency, accuracy and fluency in text-level reading, and reading comprehension), as well as in oral language (vocabulary, grammar, use of pronouns or conjunctions, use of idioms) and writing. It is often the case that [English language learners] continue to develop oral language and vocabulary skills while building core literacy skills.[694]

Multilingual students, then, need instruction and intervention on the same foundational word reading skills as other students.

This section of the report deals with tier 1 classroom instruction. For more on how school boards are implementing other aspects of RTI/MTSS, see sections 9, Early screening and 10, Reading interventions.

Ineffective methods for teaching reading

Balanced literacy or comprehensive balanced literacy approaches, cueing systems and other whole language beliefs and practices are not supported by the science of reading for teaching foundational reading skills. They have been found ineffective in many studies, expert reviews and reports for teaching all students to read.[695] The consequences of using these approaches and programs are particularly serious for students with reading disabilities and other risk factors for failing to learn to read. Research does not support that a balanced literacy approach, which focuses on teaching cueing systems for word solving and rejects a structured literacy approach, is as successful as science-based approaches, which include direct and systematic instruction in foundational word reading skills, for teaching children in at-risk groups to read.[696] Despite this, they remain prominent teaching strategies in Ontario.

Balanced literacy, cueing systems and whole language proponents assert that children learn to read naturally, largely through meaningful and authentic literacy experiences and exposure to books and other literacies. They largely reject structured literacy approaches that encompass direct and systematic instruction in the foundational skills supporting word-reading acquisition, and formal reading programs that support teachers to deliver this instruction. Whole language and its offspring, cueing and balanced literacy, emphasize learning whole words in meaningful contexts. In whole language, there is little or no systematic, direct instruction in phonemic awareness. Phonics and decoding and sounding out words are not emphasized.[697] Dr. Moats noted that balanced literacy, cueing systems and whole language approaches are characterized by:

- Little teaching about speech sounds and their features

- Not enough instruction in blending and pulling apart or segmenting the sounds in words

- Confusing phonological awareness and phonics

- Instructing teachers to avoid breaking words into their parts and teaching the letter-sound relationships

- Telling students to guess at a word from context and the first letter

- De-emphasizing “sounding out” the whole word from beginning to end

- Not systematically presenting sound-symbol relationships and/or practicing decoding words

- Using leveled books instead of decodable texts.[698]

Cueing systems

The three-cueing system follows from a whole language approach and is a central part of balanced literacy. It was first proposed in 1967 by Dr. Ken Goodman, a professor who has been described as the founder of the whole language approach. Dr. Goodman described reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game.” Dr. Goodman argued that reading is not a precise process that involves sequentially identifying letters, words, spelling patterns and language units. Rather, Dr. Goodman suggested that as people read, they play a guessing game to predict words on the page using cues: semantic cues (what would make sense based on the context); syntactic cues (what kind of word could this be, such as a verb or a noun); and graphophonic cues (what do the letters suggest the word might be). Dr. Goodman’s theory, which was based on how he thought fluent adult readers read, became the basis for the three-cueing approach for teaching young children to read.

Dr. Goodman’s theory of skilled reading and the cueing systems approach were not validated by later scientific studies of skilled reading or how to teach developing readers. One educational psychologist explained:

The three-cueing system is well-known to most teachers. What is less well known is that it arose not as a result of advances in knowledge concerning reading development, but rather in response to an unfounded but passionate held belief. Despite its largely uncritical acceptance by many within the education field, it has never been shown to have utility, and in fact, it is predicated upon notions of reading development that have been demonstrated to be false. Thus, as a basis for decisions about reading instruction it is likely to mislead teachers and hinder students’ progress.[699]

Dr. Goodman also identified miscue analysis as a way to assess students’ use of cueing systems. A miscue analysis is an observational method where the teacher listens to a student read a passage of unfamiliar text that is at least one level higher than their current reading level within a leveled reading system. The teacher observes the student’s mistakes, or miscues, to assess how the student approaches the process of reading, which cueing strategies they need to work on, and their overall comprehension of the passage. A running record is a similar observational tool that teachers use to assess a student’s oral reading behaviours.

In a 2020 article “What Constitutes a Science of Reading Instruction?” Dr. Timothy Shanahan, an internationally recognized educator, researcher and education policy-maker focused on literacy education, confirmed that “no research has shown that learning benefits from teaching cueing systems.”[700] In another recent study, seven independent reading researchers reviewed Dr. Lucy Calkin’s program which is based on the three-cueing system and widely used in the U.S. They concluded:

The program…strongly recommends use of the three-cueing system…as a valid procedure for assessing and diagnosing a student's reading needs. This is in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research…[701]

Balanced literacy

Balanced literacy has not been scientifically validated. According to Dr. Irene Fountas and Dr. Gay Su Pinnell (Fountas and Pinnell), who have developed materials that are heavily relied on in Ministry resources and used in Ontario schools, balanced literacy is a “philosophical orientation that assumes that reading and writing achievement are developed through instruction and support in multiple environments using various approaches that differ by level of teacher support and child control.”[702] [Emphasis added]

Another author explains:

[A] Balanced Literacy approach recognizes that students need to use a variety of strategies to become proficient readers and writers. It encourages the development of skills in reading, writing, speaking and listening for all students.[703]

She writes that a balanced literacy program should include (with suggested time targets for reading and writing):

Suggested targets for reading:

- Modeled reading (10 min/day)

- Shared reading (15–20 min/three days in a row for two weeks)

- Guided reading (one text/group; 15–20 min/week)

- Independent reading (20 min/day).

Suggested targets for writing:

- Modeled writing (every other day; 10–15 min)

- Shared writing (every other day; 10–15 min)

- Guided writing (2–3 times per week for 40 min)

- Independent writing (25–30 min per day). Create a body of work for reflection, assessment and growth.

A report titled Whole Language Lives On: The Illusion of “Balanced” Reading Instruction, shows how the term “balanced literacy” was adopted to conceal the true nature of whole language programs.[704] Even though balanced literacy proponents often argue it uses scientific approaches, balanced literacy fails to incorporate the content and instructional methods proven to work best for students learning to read. This is particularly harmful for at-risk students, including students with dyslexia and many others who come to school with few pre-reading skills for different reasons. Balanced literacy relies on teaching cueing systems to guess at words in text, rather than direct, systematic instruction to build students’ decoding and word-reading skills.

One expert concludes:

In summary, whole-language derivatives are still popular, but they continue to fail the students who most need to benefit from the findings of reading research. Approaches such as…balanced literacy do not complement text reading and writing with strong, systematic, skills-based instruction, in spite of their claims. Only programs that teach all components of reading, as well as writing and oral language, will be able to prevent and ameliorate reading problems in the large number of children at risk.[705]

Ontario’s approach to teaching reading: the Ontario Kindergarten Program, Grades 1–8 Language curriculum and related resources

Ontario’s Kindergarten Program

Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, 2016[706] sets out what four- and five-year-olds across the province learn “through play and inquiry.”[707]

Kindergarten is a critical time in a child’s reading development, where they must develop some core early reading skills. Students who do not have these skills by the time they enter Grade 1 or 2 are often considered at risk for difficulties learning to read.[708]

Empirical studies have shown significant variation in pre-reading skills and oral language abilities among children entering school.[709] Research has also clearly established that children entering school with less-developed pre-reading skills and oral language abilities are at a greater risk for later reading difficulties.[710]

Kindergarten programs that target reading and oral language skills using age-appropriate approaches have been found to close gaps and promote later reading success, in ways that programs that do not have this focus do not.[711]

Research also suggests that current approaches, similar to those in Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, are not enough to change young students’ developmental trajectories related to later word-reading skills, or to provide the critical vocabulary and background knowledge needed for later reading comprehension.[712]

Although the focus of this report is on word reading, the science of reading addresses other areas such as the importance of early vocabulary instruction.[713] Observational studies have shown an “overwhelming lack of attention” to vocabulary instruction, even in the earliest school years.[714] In a U.S. study examining classroom approaches like those in Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, planned vocabulary instruction was largely absent across 55 Kindergarten classrooms, and impromptu instruction about words occurred for only about eight minutes per day[715] (see similar Canadian research for older grades).[716] In classrooms with students from largely lower socioeconomic backgrounds, even fewer words were introduced per day, and fewer of these were more challenging words.[717] These findings highlight critical inequities in early literacy learning opportunities.[718]

The OHRC examined the literacy component of Ontario’s Kindergarten Program[719] as it relates to children’s skills related to decoding and word-reading development. The Kindergarten Program is deficient in several key ways.

The program does not pay enough attention to the importance of phonemic awareness skills and how to teach these in the classroom. While there are references to phonological awareness, phonemic awareness and phonics in several specific expectations, there is little discussion of the importance of these skills. There are no clear sets of reading skills that teachers are expected to teach and students are expected to learn.

There is also insufficient information on instruction for alphabetic knowledge and decoding skills, including no mention of daily phonics instruction in the Kindergarten classroom. Also, the program does not discuss the importance of monitoring students’ skills in these areas, or supporting students who are struggling in developing these reading skills.

An “Educator Reflection” in the Kindergarten Program document states: “We noticed that, when we taught a whole class about phonological and phonemic awareness, we were not really meeting anyone’s needs.” This negative anecdotal statement about class-wide instruction in phonological and phonemic awareness is inconsistent with decades of research showing that all students benefit from this form of instruction. It feeds into a myth that only some students need this explicit instruction, and discourages class-wide instruction with sounds and letters to build these foundational skills.

One Kindergarten teacher who is teaching foundational skills in a direct and explicit way in her classroom told the inquiry: “Every [student] is benefitting. My [students] are fantastic spellers, and they love it [referring to the structured literacy instruction].” She also expressed concern that Ontario’s play and discovery-based Kindergarten Program does not provide enough guidance on how Kindergarten teachers should teach foundational word-reading skills, putting students at a disadvantage when they enter Grade 1:

In Ontario, the play-based [K]indergarten [P]rogram is interpreted by some (many?) to mean play all day and no direct explicit instruction. Teachers placing a bunch of magnetic letters in the rice table is not going to teach children how to read, nor is it going to catch early strugglers. There needs to be clearer guidelines for the teaching of reading or pre-reading in kindergarten, in direct response to early screening – using a fun and playful structured literacy program.

The evidence is clear that instruction in phonological awareness, letter knowledge and sounds, and simple decoding should be included in daily instruction for all Kindergarten students. Approaches for phonological awareness start with easier, oral language activities in Kindergarten Year 1 (formerly referred to as Junior Kindergarten), such as singing and learning nursery rhymes, learning to recognize and produce rhyming words, and playing with the chunks of sound that make up words, like syllables and beginning sounds. In Kindergarten Year 2 (formerly known as Senior Kindergarten), students need to develop the critical phonemic awareness skills of identifying phonemes in the beginning, end and middle of words, and then blending and segmenting individual phonemes in words.

At the same time, Kindergarten Year 1 and Year 2 students should be taught, using engaging and age-appropriate methods, letter names and letter-sound associations, and how to use these to read simple words. Through Year 2, students should master (be both accurate and quick) the most common letters representing the roughly 44 English sounds and 36 French sounds (grapheme-phoneme associations) through explicit teaching and practice using these to read simple words, sentences and stories that are made up mostly of words students are able to decode with the associations they have already learned. Writing is an important activity in Kindergarten, and students should develop and reinforce these skills through instructional writing activities, as they learn to segment sounds in words and represent these with letters.[720]

Several inquiry school boards were concerned that a proportion of their students start school at a disadvantage. They clearly recognize that many of these students will remain at a disadvantage unless something is done. However, what was less clear was their understanding that schools can provide instruction that will help these students close the gap with peers who start school with more developed skills. The boards suggested that access to better pre-school programs and services were the solution. Although better pre-school supports could help, science-based Kindergarten classroom programming can address many of these disadvantages, such as those related to phonemic awareness and word reading.

Unfortunately, the current Kindergarten Program in Ontario maintains, and does not alleviate, literacy disadvantages for the large numbers of students who start school with less-developed formal pre-reading and reading skills. This includes children who may have a biological predisposition to reading disabilities/dyslexia. Complete literacy programs must include instruction in word-reading skills, as well as the many other components that help develop strong and motivated readers. Emphasis on word-reading skills is essential but is largely absent in Ontario’s Kindergarten Program. This is a significant obstacle limiting the reading and literacy development of far too many Ontario children.[721]

The Association of Psychology Leaders in Ontario Schools[722] stressed the importance of introducing these skills in Kindergarten, in the context of play-based learning:

Foundational reading skills can be incorporated into regular classroom instruction in the early years and in ways that maintain the integrity of the play-based philosophy. Purposeful play is play nevertheless. There exists an opportunity for boards to implement programs that teach foundational reading skills in the early years, and emphasize the oral language and phonological awareness skills that are critical for reading development. Not doing so would be to the detriment of our children.

Ontario’s Grades 1–8 Language curriculum

Curriculum is set by the Ministry.[723] Of note, the Ontario Language curriculum is the oldest elementary curriculum in use in Ontario,[724] and one of the oldest elementary language curricula in Canada.[725] The Ontario Language curriculum was last updated over 15 years ago, in 2006. According to the Ministry, curriculum has a shelf-life of 10 to 15 years.[726] Based on its age alone, this curriculum is due for an update.

The Ontario Language curriculum outlines the knowledge and skills students are expected to achieve by the end of each grade. It sets out mandatory learning expectations, and what is taught in each grade must be developed based on these learning expectations. Teachers use their professional judgment to decide how to teach the curriculum.

The Ontario Language curriculum focuses on the use of the three-cueing system as the primary approach students will be taught to read words. The Ontario Language curriculum makes it clear that this involves looking for clues to predict or guess words based on context and prior knowledge. It defines cueing systems as:

Cues or clues that effective readers use in combination to read unfamiliar words, phrases, and sentences and construct meaning from print. Semantic (meaning) cues help readers guess or predict the meaning of words, phrases, or sentences on the basis of context and prior knowledge. Semantic cues may include visuals. Syntactic (structural) cues help readers make sense of text using knowledge of the patterned ways in which words in a language are combined into phrases, clauses, and sentences. Graphophonic (phonological and graphic) cues help readers to decode unknown words using knowledge of letter or sound relationships, word patterns, and words recognized by sight. [Emphasis added.]

As explained by the validated models of skilled reading presented earlier, effective readers recognize words accurately and quickly. They do not need to use their attention to guess at words based on cueing systems. Context can help with recognizing the rare word whose orthography is unfamiliar and not easily pronounced. It should not be a primary or frequent strategy for reading words.

For young children learning to read, the written form of almost all words is “unfamiliar.” Starting to learn to read by integrating these cueing systems in texts is not effective for most children, and not efficient for any child.

In the current Ontario Language curriculum, one of the overall expectations for each grade is that students will be able to “use knowledge of words and cueing systems to read fluently.” As discussed below, Ontario’s teaching guides also emphasize cueing systems as the primary approach for students to learn the written code of spoken language. Therefore, the curriculum emphasizes teaching cueing systems for word reading rather than directly and systematically teaching students the written code of spoken language. With this cueing system approach, many students fail to build accurate and efficient word-reading skills, which are the “hallmark of skilled word reading.”[727] Indeed, failing to directly teach skills and knowledge needed for accurate and efficient reading in the earliest grades can start the Matthew Effect in reading (described in section 4, Context for the inquiry), where students with poor early word-reading skills get further and further behind in all aspects of reading and the positive consequences of reading, such as building vocabulary and knowledge of the world.[728]

The Ontario Language curriculum defines phonological awareness, phonemic awareness and phonics but it does not require these be taught or provide guidance on how these should be taught.

The Ministry’s Guide to Effective Instruction in Reading

The Ministry also develops resources to support instruction. One significant resource related to early reading instruction is the Ministry’s A Guide to Effective Instruction in Reading, Kindergarten to Grade 3, 2003 (the Guide). School boards reported that they rely on the Guide in delivering the Language curriculum.

The Guide emphasizes the role of the three-cueing system and related balanced literacy approaches for teaching students to read words. For example, it outlines the following word guessing skills in a table entitled “The Behaviours of Proficient Readers.”

Word-solving skills

Proficient readers:

Use semantic (meaning) cues:

- use illustrations from the text to predict words

- use their prior knowledge as an aid in reading

- use the context and common sense to predict unfamiliar words

Use syntactic (structural) cues:

- use their knowledge of how English[729] works to predict and read some words

- use the structure of the sentence to predict words

Use graphophonic (visual) cues:

- analyze words from left to right

- use their existing knowledge of words to read unknown words

- notice letter patterns and parts of words;

- sound out words by individual letter or by letter cluster

Use base or root words to analyze parts of a word and to read whole words

Integrate the cueing systems to cross-check their comprehension of words:

- combine semantic (meaning) and syntactic (structural) cues to verify their predictions

- cross-check their sense of the meaning (semantic cues) with their knowledge of letter-sound relationships and word parts (graphophonic cues).

Although the description of graphophonic (visual) cues appears to suggest that the sounds and letter patterns in words are part of the three-cueing system, this is at best a passing reference to a few of the fundamental skills needed to read words. Instructions on how to use graphophonic clues often promote looking at the first letter/sound in the word and then guessing what might fit for the whole word in the context of the sentence. For example, in a section called Sample Questions and Prompts to Promote Students’ Use of the Three Cueing Systems, the Guide suggests the following questions to help students use graphophonic cues:

- What were the rhyming words in this story?

- What word do you see within that bigger word? (Prompt students to look for the root word in a word with a prefix or suffix, or for the two words that make up a compound word)

- What is the first letter (or last letter) of the word?

- What sound does that letter (or combination of letters) make?

- What other words start with that letter and would fit into this sentence?[730]

These examples of how to process the letters within words are time- and attention-consuming – the exact opposite of skill acquisition where words become recognized more and more automatically. The National Reading Panel Report noted that some instruction in phonics as one part of graphophonic prompts is not sufficient:

Whole language teachers typically provide some instruction in phonics, usually as part of invented spelling activities or through the use of [graphophonic] prompts during reading (Routman, 1996). However, their approach is to teach it unsystematically and incidentally in context as the need arises.

Although some phonics is included in whole language instruction, important differences have been observed distinguishing this approach from systematic phonics approaches.[731]

The Guide has a later section on phonemic awareness, phonics and word study. However, the three-cueing system is presented throughout as the primary instructional approach to reading words in text. Even within the discussion of phonemic awareness, phonics and word study, guessing strategies are promoted. For example, in a section on word-solving and word study, teachers are once again encouraged to have students predict words, think about what word would make sense in context and look at the pictures for clues.[732] Decoding or sounding out words is often presented as one of the last strategies for word analysis when it should be the first[733] and based on effective classroom instruction on how to decode words.

Combining cueing systems with decoding strategies is not an effective approach to reading instruction and results in confusion for students. The U.K.’s Primary Framework for Literacy and Mathematics noted:

…attention should be focused on decoding words rather than the use of unreliable strategies such as looking at the illustrations, rereading the sentence, saying the first sound or guessing what might “fit.” Although these strategies might result in intelligent guesses, none of them is sufficiently reliable and they can hinder the acquisition and application of phonic knowledge and skills, prolonging the word recognition process and lessening children’s overall understanding. Children who routinely adopt alternative cues for reading unknown words, instead of learning to decode them, later find themselves stranded when texts become more demanding and meanings less predictable. The best route for children to become fluent and independent readers lies in securing phonics as the prime approach to decoding unfamiliar words.[734] [Emphasis added.]

For children learning to read, almost all words are unfamiliar words.

Another recent report by leading reading researchers confirms that three-cueing as the way of teaching students to read and as a first strategy for students reading unfamiliar words is problematic and inconsistent with the scientific evidence:

Th[e] endorsement of the three-cueing system gives teachers explicit permission to center instruction on the three-cueing system rather than the more productive and research-based incorporation of phonics instruction. The best and overwhelming body of research strongly supports that letter-to-sound decoding is the primary system used by proficient readers to read text while it is only poor readers who rely on use of partial visual cues to guess at words…. The promotion of the three-cueing system…will dilute the work of the phonics materials by prompting teachers to focus on analyzing running records for errors based on meaning and syntax rather than leveraging taught foundational skills.[735]

Other Ministry resources

The Ministry of Education publishes several resources on early literacy and special education. It states that these resources support instruction, and educators may choose to use these resources if they find them useful.

The inquiry reviewed these resources and found that they also fail to promote an effective and systematic evidence-based approach to teaching students how to read. This is not surprising, given that the Ontario Language curriculum and the Guide are the primary resources for teachers, and any additional Ministry resources follow the curriculum.

Consistent with the Ontario Language curriculum and Guide, these resources promote whole language approaches. For example, a Ministry guide to support boys’ success in literacy, Me Read? No Way! A Practical Guide to Improving Boys’ Literacy Skills, 2004 acknowledges that gender is a significant factor in reading achievement and that boys score lower on reading tests, are more likely to be placed in special education classrooms, have higher dropout rates and are less likely than girls to go to university.[736]

This resource identifies 13 “strategies for success” for improving boys’ reading. None of the strategies reference teaching early foundational reading skills effectively to improve word reading, including teaching phonemic awareness, phonics and decoding. All the strategies suggest that if boys find reading more interesting, relevant and fun, they will be better readers. This guide promotes the problematic balanced literacy approach as a best practice.[737]

Focusing only on a lack of student engagement to explain why students do not read well perpetuates stereotypes about students who do not learn to read without instruction and students with reading difficulties. It suggests that if students simply find something they are interested in and apply themselves, they can improve their reading. It fails to recognize that if students are not able to read the words in texts, it limits their reading comprehension, does not increase reading skills, and has a negative impact on their desire to engage in reading. The notion that some students, especially boys, are not motivated to learn is constructed on negative and gendered stereotypes.

The Ministry’s basis for adopting the three-cueing system

The three-cueing system and balanced literacy models in the Ontario Language curriculum, the Guide and other Ministry resources were not recommended for developing early word-reading skills by the Kindergarten to Grade 3 expert panel in the Early Reading Strategy: Report of the Expert Panel on Early Reading in Ontario.

The OHRC asked the Ministry why it decided to adopt the three-cueing system, and what scientific support it had for the three-cueing system. The Ministry advised that cueing systems were referenced in Literacy for Learning: The Report of the Expert Panel on Literacy in Grades 4 to 6 in Ontario (2004).[738] This Grade 4 to 6 expert report states that it builds on the foundations for literacy that are laid in a child’s early years. It also says that it builds on the earlier work of the Kindergarten to Grade 3 expert panel. However, this panel did not recommend three-cueing or balanced literacy approaches for word reading.

The Grade 4 to 6 expert report appropriately suggests that cueing systems can be used by students in Grades 4 to 6 to “make meaning from increasingly complex texts.” It does not suggest that cueing systems be used to teach foundational word reading skills to students in Kindergarten through Grade 3. The research shows that context is important to reading comprehension or making meaning from text after words have been decoded.[739] However, using context is not useful as a primary word decoding strategy. When children encounter a word they have not seen before, their first approach should be to use decoding skills to sound it out.[740]

Therefore, the evidence gathered in the inquiry shows that the Ontario Language curriculum, the Guide and related resources were not developed in response to the expert or scientific evidence available at the time. There was not, and still is not, a sufficient basis to support the use of the three-cueing system and balanced literacy for teaching early word reading in Ontario.

School board approaches to teaching reading

Given the prevalence of three-cueing and balanced literacy in the Ontario Language curriculum, the Guide and other resources, it is not surprising that the eight inquiry school boards all reported using these ineffective approaches to word-reading instruction in their schools.

The OHRC asked the boards to provide documents, data or information explaining their approach to teaching reading. The OHRC also asked questions in its meetings with each board to better understand if they are teaching phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding and word-reading, and their views on whether current approaches are consistent with the science of reading.

Emphasis on three-cueing and balanced literacy

All boards reported following the Ontario Language curriculum as required, as well as relying on the Guide and other Ministry resources. The boards said that in addition to cueing systems, they use either a balanced literacy or comprehensive (balanced) literacy approach to teaching reading. The key elements that appear to distinguish comprehensive balanced literacy from balanced literacy are an emphasis on oral language, reading, writing and media literacy, as well as teachers having flexibility to divide time among the four primary teaching strategies (modelled, shared, guided and independent reading) in response to the perceived needs of their students.[741] The majority (59%) of educators[742] who responded to the OHRC’s educator survey also identified balanced literacy as the predominant approach to teaching reading in Ontario.

The inquiry school boards also reported relying heavily on resources from whole language and balanced literacy proponents such as Drs. Fountas and Pinnell, Dr. Brian Cambourne, Dr. Marie Clay, and Dr. Lucy Calkins for instruction, assessment and intervention. These include PM Benchmarks, Running Records, Observational Survey of Literacy Achievement and Miscue Analysis for assessment as well as Levelled Literacy Intervention (LLI) and Reading Recovery® for interventions (for a detailed discussion of assessment and intervention, see sections 9, Early screening and 10, Reading interventions).

One school board described its understanding of literacy development, based on Cambourne’s Conditions of Learning:

…educators must understand that: literacy is developmental; not all children reach the same developmental phase at the same time; attitude can play a large part in the success of the student; reading and writing tasks must be linked to prior knowledge and experience; and learning language requires much social interaction and collaboration. [Emphasis added.]

Unfortunately, these types of misconceptions can lead educators to believe that students who are not learning to read are not developmentally ready or are not trying hard enough. Many students and parents reported being told that delays in learning to read are normal, or that students are not learning to read because of a lack of effort. However, these delays were later recognized as early signs of failing to learn to read due to the lack of direct and systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills. These reported observations are consistent with findings from research.[743]

The boards were asked if they believe they are following a whole language or structured literacy approach to teaching reading. Two boards acknowledged that their literacy programs follow a whole language approach. One board reported following a structured literacy approach. Other boards felt their approach incorporated elements of both. However, the overall approaches of all the school boards, with a few possible exceptions (described below), do reflect a whole language philosophy.

School board leaders opined that a whole language approach is not at odds with teaching phonological awareness or that whole language and direct instruction/structured literacy approaches can be combined. In fact, whole language approaches do preclude systematic and explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, because a central belief of whole language is that individual reading skills are not taught outside of “authentic” or real-world reading activities. Further, the three-cueing system that is the primary approach to word-reading instruction within this framework is directly opposed to direct and systematic teaching of decoding skills.[744]

Board representatives were asked if they believe the current Ontario Language curriculum and their approaches to reading instruction are working well or should be changed. It was apparent that many board leaders were not familiar with the overwhelming evidence that cueing systems and balanced literacy are far less effective approaches for teaching early reading skills and leave many vulnerable students at risk for not learning these skills. Boards described balanced literacy as “very highly regarded as the way to teach reading,” as it is “still taught in faculties of education” and believed balanced literacy researchers “are still at the forefront.” One board said it felt “confident” that balanced literacy is the way to teach students to read and to get most students reading at grade level, even though a significant proportion of this board’s students, particularly students with learning disabilities and special education needs, are not meeting provincial standards on EQAO testing.

Boards that recognized the need to improve literacy outcomes for more students could not always identify how their current approaches to teaching reading are not working for these students. It was unclear how these boards expected to increase student success in reading without fundamentally changing how students are taught to read. They did not appear to know about the scientific evidence on effective instruction in early reading skills.

Several boards suggested that the current approach simply needs minor adjustment to provide a bit more guidance on how to approach phonological awareness and “word work,” or clearer expectations for what should be taught and learned in each grade. One board noted that teachers are more comfortable with using cueing systems than with delivering direct and systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills, and could use “some additional guidance” on the latter. Several boards commented that the Ontario Language curriculum provides little guidance on what the expectations are for each grade, so they are left to interpret the curriculum to decide what to focus on in each grade. These boards suggested that clearer guidance on what should be taught in each grade could be helpful and promote greater consistency across Ontario.

One board clearly acknowledged that the current Ontario Language curriculum and approaches to teaching reading are not consistent with the science of reading. This board said that their speech-language pathologists and psychologists have informed them that the current curriculum does not support direct, systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills or structured literacy. The board noted that teachers must follow the curriculum, which is not consistent with the science of reading. The board reported being concerned about how to “honour the Ontario curriculum as required while also adapting to what the science of reading is telling them.”

Several school boards explicitly said they believed that they sufficiently address “word work” or “word study” within their current approaches. For example, one board reported allotting 2–3 minutes each day for letter or word work in their guided reading block, which they felt was enough to help students “become quick and flexible at using principles that are important in solving words at this level.”[745] Other boards were not able to provide any specifics on how much time is spent on “word work” or “word study,” indicating that this is left to each teacher’s judgment with no means to monitor whether any direct and systematic instruction of foundational word-reading skills is taking place.

When asked if teachers are required to teach phonological awareness and phonics, one board said that “required is a strong word” and suggested teachers may spend some time working on phonological awareness with the whole class as “an exposure ideal,” but would more likely do so with smaller groups of students. This was consistent with the inquiry’s finding that if these skills are addressed at all, it is through “mini lessons” with small groups of students at the teacher’s discretion. This is not the systematic instruction in the written code that is supported by decades of research.

As well as asking the boards about their approach to reading instruction, the OHRC, with the help of its experts, reviewed the documentation the boards provided. With a few exceptions, the OHRC found little information in the documentation or outlined classroom materials showing that boards include a direct and systematic approach to phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding and word reading fluency (and word structure or morphology in more advanced lessons). Further, the instructional cycle of focusing on books through modelled, shared, guided and independent reading leaves little room for any emphasis on direct instruction to teach children the code of written language.

Lessons most often take the form of short “mini lessons” that appear to be based on what teachers notice the students need, such as an aspect of reading comprehension, vocabulary or graphophonic information. This model of ad hoc instruction does not incorporate and is inconsistent with direct and systematic whole-class instruction in the foundational skills of word reading that aims to increase all students’ decoding skills.[746] Indeed, the reported approaches are inconsistent with Universal Design for Learning and RTI/MTSS frameworks for inclusive education.