Introduction

When reading interventions are early, evidence-based, fully implemented and closely monitored, they are highly effective in reducing reading failure.[994] Students in all grades, from Kindergarten to high school, should have access to effective interventions for reading difficulties. With effective classroom instruction and early interventions, fewer students will need interventions in the older grades, where they are more time-consuming and can be less effective.[995]

Evidence-based reading interventions are a necessary part of an effective Response to Intervention (RTI)/Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS). An RTI/MTSS framework alone does not ensure success in teaching all students to read. To be effective, this framework must include classroom instruction, assessment and intervention practices that are all consistent with current reading science. See section 8, Curriculum and instruction and section 9, Early screening. Although all inquiry school boards reported using an RTI/MTSS framework, they are not implementing the key aspects and elements that make up a successful tiered framework.

In Ontario, many young students need interventions targeting foundational word-reading skills because classroom instruction is not based on research science. Yet, the inquiry found that schools are not providing these interventions. Their first line of action is to provide ineffective commercial programs that have little basis in science. These programs mirror instruction approaches that do not work in the classroom. Some boards have developed their own approaches, but these are isolated, incomplete and ad hoc. These in-house programs have not been adequately evaluated to establish confidence in their effectiveness, or to support their continued use.

When boards do use evidence-based interventions, they often provide them too late and only to a limited number of students. When interventions are delayed, their effectiveness can be reduced, and the critical period when future lifelong reading difficulties could have been prevented is lost. Interventions delivered later are more intensive, time-consuming and costly, and may not be as effective as those delivered earlier, especially in addressing word- and text-reading fluency.[996]

Decisions on who receives an intervention and which intervention they receive are unclear or based on inappropriate beliefs and unscientific criteria. As well, school boards do not have the necessary systems in place to monitor students’ progress in reading and make sure all students who need interventions receive them.

Although our education system acknowledges the importance of an evidence-based approach, this has not translated into changes in beliefs and practices. Authoritative reports from more than two decades ago[997] have outlined what approaches are needed to teach reading effectively. Still, Ontario’s education system promotes mostly unscientific approaches. Using contextual cues as the main strategy to decode words is not supported by evidence – yet this is the primary approach to reading curriculum, instruction, assessment and intervention.

Ontario’s approach to reading interventions is insufficient. When, as a result, students cannot read words accurately and quickly, our education system has failed. Many families have given up on the public education system and opted to pay for private services. Families that cannot afford to pay or do not have these services in their communities must navigate a complex system and hope there are enough spots to get into an evidence-based intervention program, if it exists, at their school. Many families are not even told the school may provide such programs.

There are better, more systematic and scientific ways to select and implement reading interventions. Research shows that the earlier children with reading difficulties receive effective interventions, the more likely they are to fully catch up with their peers in the foundational reading skills that are essential for making continued yearly gains in reading.[998]

Effective Response to Intervention (RTI)/Multi-tier System of Supports (MTSS)

Effective RTI/MTSS includes instruction and interventions at each tier based on sound research evidence.[999] This evidence comes from a body of robust and reliable empirical studies that examine and show the effectiveness of particular instructional approaches and intervention programs.

Evidence-based practice means using the best available research in making decisions.[1000] It requires a commitment to continuously updating and improving practices based on the science.[1001]

Successful RTI/MTSS for students with or at risk of reading disabilities includes these key components:

- Evidence-based instruction at each tier starting with classroom instruction, early interventions (Kindergarten to Grade 1), and later interventions (Grades 2–5; 6–8; 9 and above)

- Universal early screening that includes valid and reliable measures to identify students, and to provide immediate interventions

- Early, evidence-based interventions targeting the foundational skills of sound-letter knowledge, phonemic awareness, decoding and word-reading accuracy and fluency, including more advanced orthographic patterns, syllables and morphemes

- Clear and appropriate decision-making rules for choosing evidence-based programs for classroom instruction and tiered interventions, and for matching students to intervention programs (for example, standardized scores on assessments of foundational word-reading skills, rather than setting cut-offs that may not be valid, such as the student having to be a certain number of years behind in their reading)

- Valid and reliable progress monitoring and outcome measures for interventions

- Clearly identified rules and guidelines for decisions on individual students, at each juncture within the multi-tiered system

- Distributing interventions to make sure all students have access to effective interventions

- Rigorous methods for ensuring program fidelity (implementing an intervention as intended) and for conducting program evaluation (for example, standardized word-reading, fluency and comprehension measures)

- Adequate resources to implement the interventions, and provide quality teacher professional development and ongoing coaching.

Classroom instruction and early interventions (Kindergarten and Grade 1) are key to preventing future word-reading difficulties. They have the potential to help students catch up before they fall far behind and reduce the number of students needing interventions. With evidence-based instruction at each tier, almost all children (90–95%) can develop solid word-reading accuracy and fluency.

When children with weak reading skills do not receive effective early interventions, there is a high likelihood they will remain poor readers throughout their school years.[1002] In fact, students who get a quick start with their word-reading skills enjoy and engage in reading more, and that reading practice in turn strengthens their basic reading skills. Students who get a slow and difficult start in word reading are less likely to choose to read. Reading skills are critical across most school subjects, and students with reading difficulty are at risk of falling behind their peers in many subjects. These “rich get richer” or Matthew Effects were first proposed in the context of reading by Dr. Keith Stanovich, an expert on the psychology of reading.[1003]

Research has clearly shown the benefits from intervening earlier.[1004] For example, in one study, students who received interventions in Grades 1 and 2 made gains in foundational word-reading skills at almost twice the rate of students receiving the intervention in Grade 3, relative to control groups.[1005]

When students, even as early as Grade 2, are behind in word reading, their fluency starts to fall further behind peers who are reading more and building up more and more grade-appropriate words that they automatically recognize. The most important contributor to text-reading fluency is word-reading fluency (also called word-reading efficiency).[1006] Text-reading fluency becomes very hard to address beyond the Kindergarten and Grade 1 years.[1007]

Effective classroom instruction (tier 1) includes evidence-based, explicit teaching that targets decoding and word-reading accuracy and fluency. See section 8, Curriculum and instruction.

In a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, teachers use systematic approaches and programs that allow the greatest number of students to be successful and gain the required skills and knowledge. These programs provide classroom instruction for all children. They set out effective differentiation, and provide extra and more scaffolded instruction and practice for students not progressing at the same rate as their peers. Effective differentiation provides extra support to these students so they reach average word-reading skills, rather than falling behind.

A science-based curriculum builds solid foundational word-reading, fluency and spelling skills for all students. Curriculum that promotes a different approach results in too many students needing interventions and confusion for students receiving those interventions.

Strategies learned in effective intervention programs must be supported in the classroom setting. If the current Ontario Language curriculum is not revised (classroom/tier 1), evidence-based tier 2 intervention will be at odds with tier 1, and at-risk students’ foundational skills will not be reinforced in the classroom. Also, once interventions have ended, classroom practices that are not evidence-based will not support students continuing to develop the necessary skills. Ontario’s 2003 Expert Panel on Early Reading noted:

Successful interventions are strongly linked with regular classroom instruction, are supported by sound research, reflect an understanding of effective reading instruction….It is critical that interventions be measured against these criteria, and that their effectiveness in helping children with reading difficulties be carefully assessed and monitored.[1008]

Screening and progress monitoring help determine the level or intensity of intervention needed. All students should be screened throughout the early years to identify who is not developing the required foundational word-reading skills, despite evidence-based instruction. These students should receive intensive intervention and their progress should be monitored. Based on their progress, students may (1) need more intensive intervention, or (2) continue to need the current amount of intervention, or (3) discontinue their current intervention.[1009]

When students in Kindergarten and/or Grade 1 are not keeping up through classroom instruction and differentiation, tier 2 interventions should be used to prevent long-term reading difficulties. Waiting to see if these students will catch up without an effective foundational skills intervention is not following evidence-based practices.

Interventions generally occur daily in focused short blocks of time.[1010] Tier 2 and tier 3 interventions can be distinguished by how intense, long and often the intervention is delivered.[1011]

At tier 2, evidence-based interventions must target the foundational skills of sound-letter knowledge, phonemic awareness, decoding skills and word-reading accuracy and fluency. Like tier 1 programs, these usually incorporate teaching morphology and syllable structures. The focus on learning to read words means learning and integrating written words with their pronunciations and meanings. These areas will be consistent with areas taught in evidence-based tier 1 instruction. Tier 2 should be completed with a small group of students, with sufficient time and intensity for an explicit, evidence-based foundational skills program/intervention.

When effective tier 2 intervention is delivered properly and for enough time for Grades 2 and up, it will address critical reading problems. The few students who continue to be behind peers in foundational word reading and spelling will be further ahead having had effective tier 1 instruction and tier 2 intervention, and will benefit further from tier 3 interventions.

Tier 3 should consist of approaches that incorporate more intensive use of tier 2 intervention programs, or some more specialized programs, often with smaller groups, and with more explicit instruction and scaffolded practice,[1012] sufficient cumulative review to ensure mastery of the skills, and more time in the intervention.

No single reading intervention will completely address every student’s reading difficulties. Some reading difficulties/disabilities will be more severe than others. Estimates[1013] are that 3–5% of students will have word-reading problems that are less responsive to even effective interventions.[1014] School boards must have evidence-based interventions at each tier to help reach all students. If they do not, the percentage of students who are less responsive to interventions will be much larger.

Further, in fully evidence-based RTI/MTSS systems, some students with reading difficulties (about 10%) will continue to need extra supports in reading and writing, such as accommodations and technology, to optimally access the curriculum.

Multilingual learners

With appropriate instruction, multilingual students can learn phonological awareness and decoding skills in the language of instruction (English or French) as quickly as students who speak English as a first language.[1015] The specific difficulties that multilingual learners (often referred to as English language learners) may face are fairly predictable and can be addressed with proactive teaching that focuses on potentially problematic sounds and letter combinations.[1016] Of course, multilingual learners will need instruction in other aspects to fully address reading comprehension and written language.[1017] Still, multilingual learners need instruction and intervention on the same foundational word-reading skills as other students. As described by Dr. Esther Geva, an Ontario psychologists with expertise in culturally and linguistically diverse children, and her colleagues:

Instruction for [English language learners] should be comprehensive and include instruction in the core areas of reading (phonological awareness, phonics, word level fluency, accuracy and fluency in text-level reading, and reading comprehension), as well as in oral language (vocabulary, grammar, use of pronouns or conjunctions, use of idioms) and writing. It is often the case that [English language learners] continue to develop oral language and vocabulary skills while building core literacy skills.[1018]

Examples of reading interventions used in some Ontario boards

Some of the most widely used interventions reported by the inquiry school boards are not shown to be effective for any tiers within RTI/MTSS. For example, there is little to no scientific evidence supporting Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI) or Reading Recovery®.

Inquiry boards often use LLI as a first intervention for elementary school students. No rigorous research could be found to support its effectiveness for these young students with reading difficulties. The program does not align with research on approaches that have been shown to be effective with young children to prevent later reading difficulties, or with older students with reading disabilities.[1019]

Some educators, students and parents have reported favourably on using LLI.[1020] However, self-reports and observations of increased student confidence with levelled books is not a substitute for building the foundational word-reading skills that will allow children to continue to make the required gains each year. See section 8, Curriculum and instruction and section 9, Early screening for a discussion on levelled books and running records. Many survey respondents told the inquiry that LLI and Reading Recovery® were ineffective for students.

The OHRC is concerned with school boards’ use of Reading Recovery® because it focuses on cueing systems, levelled readers and running records. There has been more research on Reading Recovery® than LLI. However, the adequacy of the program and research has been consistently contested.[1021]

Programs without a strong evidence base or that are based on the three-cueing approach should not be used for students with reading difficulties. Ineffective programs will delay student progress.

Some school boards in Ontario use commercial programs that have research to support their effectiveness or are aligned with the research on effective classroom instruction and interventions.[1022] These programs target the foundational skills necessary for beginning and struggling readers. They can be provided for the different tiers, including tier 1 (classroom instruction that is necessary to prevent many reading difficulties from occurring).

Many of these interventions include progress monitoring to track a student’s progress and inform intervention-based decisions. However, school boards should also use standardized measures at pre-determined periods, and use them consistently across all interventions. These measures should include word-reading accuracy and fluency, and text reading fluency. This will allow boards and the Ministry to compare and judge the effectiveness and general appropriateness of different programs.

Some instructional programs are best suited to whole classroom implementation (tier 1). When interventions are used in Kindergarten to Grade 1, they are used to prevent reading difficulties/disabilities from developing for many students. Other interventions work best for small groups (tier 2). Programs that are used with increased intensity or include more specialized intervention are reserved for the final tier (tier 3).

Several programs are briefly described below and categorized by their potential place within an RTI/MTSS system. This list is not an endorsement of specific programs. Instead, it provides examples of evidence-based programs.[1023]

The list moves broadly in the following order:

- Whole classroom and/or tier 2 early interventions

- Tier 2 or 3 interventions

- Tier 3 interventions

- Interventions that may be viewed as supplements, as these are primarily available as online programs.

SRA Open Court Reading

SRA Open Court Reading[1024] has comprehensive English Language Arts programs for students in Kindergarten to Grade 5. The Foundational Skills Kits are stand-alone programs for students in Kindergarten through Grade 3 that target the word-reading accuracy and fluency reading skills that are the focus of this inquiry. These programs make up these critical components of complete English Language Arts classroom instruction.

The Open Court Foundational Skills programs are aligned with research on direct, systematic instruction on critical word-reading foundational skills, and have been shown to be effective for classroom-wide instruction for all children, and for preventing future reading difficulties for most students.[1025]

The Foundational Skills kits also provide classroom teachers with small-group instruction for differentiating and supplementing whole-class instruction for students who are not progressing as quickly, and for students who are learning English as an additional language. The focus on word-reading accuracy and fluency is consistent with learning and integrating the forms of written words with the pronunciations and meanings of words.

Word Analysis Kits are available for Grades 4 and 5, and focus on classroom instruction on word analysis (syllable and morphemic analysis) for reading and understanding harder words in increasingly complex texts.

Wilson Fundations®

Wilson Fundations®[1026] is a classroom program available for students in Kindergarten to Grade 3 and teaches phonemic awareness, sound-symbol relationships, word study and spelling, sight word reading and fluency. Some components are also aimed directly at vocabulary, oral language and reading comprehension strategies. The program has been shown, in independent research, to improve students’ foundational reading skills.[1027] It can also be used as a tier 2 intervention for Kindergarten to Grade 3 students who are having difficulty acquiring word-reading accuracy and fluency.

Firm Foundations

The Firm Foundations program was developed in British Columbia by school teachers and psychologists of the North Vancouver School District.[1028] This play-based program consists of games and activities that address the following skills: vocabulary, rhyme detection, syllable detection and segmentation, phoneme detection and segmentation and knowing the sounds of letters. It can be used as a classroom-based program in Kindergarten and early primary classrooms. There is evidence to support its use for children with a wide variety of backgrounds, including multilingual students and students with mixed socio-economic levels.[1029] The program was designed to be sensitive to the needs of both multilingual students and students speaking English as a first language.

Remediation Plus Systems

Remediation Plus Systems[1030] was developed in Canada in 1999. The program has explicit systematic phonics instruction, including targeting phonemic awareness in the context of building decoding and spelling skills and knowledge. Remediation Plus can be delivered through whole-class instruction in elementary grades, or implemented as small-group tier 2 intervention for all grades.

Remediation Plus Systems is used in some school boards in Ontario, Alberta, Labrador/Newfoundland and Manitoba, including in Labrador Innu and Nishnawbe Aski Nation schools. Some Canadian schools implement this program to teach reading to whole classrooms of students in Kindergarten to Grade 3, and other schools use it as a tier 2 intervention.

SRA Early Interventions in Reading Skills

Early Interventions in Reading Skills is a tier 2 intervention for Kindergarten to Grade 3 students who experience difficulty in foundational word-reading skills. It works in concert with core reading programs to provide intense early intervention. This program is consistent with research on early interventions.[1031]

Empower™ Reading (spelling and decoding)

Empower™ is a Canadian-developed intervention program designed to support students with significant reading difficulties. It was developed by Dr. Maureen Lovett, an expert in reading disabilities and early reading interventions, and her team from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, and has been well-researched. The Spelling and Decoding program is available in Grades 2 to 5 and Comprehension and Vocabulary in Grades 6 to 8. It can be appropriately used as a tier 2 or tier 3 intervention.[1032] The program is delivered four or five days a week for 60 minutes to small groups of students. Instructors teach foundational reading skills directly and explicitly combined with metacognitive strategy instruction (applying and monitoring specific strategies to guide word decoding and analysis for reading simple and complex words).

The program is based on a rigorous body of research that shows it improves students’ ability to decode taught and untaught words, while also building their ability to strategically apply learned knowledge to read multisyllabic words.[1033]

While samples in studies have been a majority of White students,[1034] specific research has examined students’ outcomes based on a range of factors. A large-scale investigation has shown that students have responded equally well based on different racial backgrounds,[1035] socioeconomic status,[1036] IQ levels[1037] and for multilingual students[1038]. A recent study showed that students who had both ADHD and a reading disability showed gains in reading when provided with a similar program.[1039]

SRA Reading Mastery and Corrective Reading

Reading Mastery[1040] provides systematic instruction in foundational reading skills to students who experience reading difficulties in Kindergarten to Grade 6. Reading Mastery can be used as an intervention program for struggling readers (tier 2), as a supplement to a school’s core reading program (increasing classroom support to students experiencing difficulty in the early years), or as a class-wide program in schools with many students at risk for not developing accurate and fluent reading skills.

Corrective Reading targets reading accuracy (decoding), fluency and comprehension skills of students in Grade 3 and up who are experiencing significant reading difficulties. It can be implemented in small groups of four to five students or in a whole-class format. Corrective Reading is intended to be taught in 45-minute lessons four to five times a week. This program may be thought of as tier 3 for students in Kindergarten to Grade 3, but tier 2 for older students with reading difficulties/disabilities/dyslexia.[1041]

The programs reflect the research-based practices recommended by the National Reading Panel, and studies have shown their effectiveness in improving reading skills.[1042] The programs include explicit, systematic instruction in five critical strands: phonemic awareness, letter-sound correspondences, word recognition and spelling, fluency, and comprehension.

SpellRead™

SpellRead™[1043] was developed in Atlantic Canada. It is an intervention program for all students with difficulties in word-reading accuracy and/or fluency, with or without a diagnosis, including for multilingual students who are learning English at the same time as they are learning the curriculum. The complete program can be delivered over an academic year and is suitable as a tier 2 intervention for Grades 1 to 12, or as a tier 3 intervention.

Instruction focuses on learning sound-letter mapping and decoding accuracy, all the way through to learning frequent morphemes and syllable patterns and reading multisyllabic words. The focus is initially on students building accuracy and then making skills automatic, and increasing word- and text-reading accuracy, fluency and resulting comprehension.

The program can be delivered to small groups of three to six students, and includes practice using the reading skills in reading real books. Studies in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and the U.S. have shown the intervention has positive effects on students’ decoding skills, word reading, reading fluency and reading comprehension.[1044]

Wilson Just Words®

Wilson Language Training® also has a tier 2 program called Just Words®.[1045] This program targets the word-reading accuracy and fluency problems of children with word-reading difficulties/disabilities/dyslexia.

Wilson Reading System® 4th Edition

Wilson’s Reading System®[1046] is a tier 3 reading intervention. It draws heavily on Orton-Gillingham principles. Orton-Gillingham is not a specific program but a structured literacy approach. The approach is systematic and cumulative – each lesson builds on the initial concept learned. It is also explicit – it uses direct phonics instruction.[1047]

Wilson Reading System® is an intensive program designed for students not making progress in other interventions. The depth of support and breadth of skills targeted by this program reflect its status as a tier 3 program.[1048]

Lindamood Phoneme Sequencing® (LiPS®)

The LiPS®[1049] program teaches struggling readers in Kindergarten to Grade 3 the skills they need to decode words, including a focus on phoneme-level awareness, identifying the sounds represented by letters in words, and blending these to decode words.

Teachers work with students in small-group or one-on-one settings to help them become aware of the mouth formations and movements to produce speech sounds. This can be helpful for students who do not respond to tier 2 intervention and have persistent difficulties with phoneme-level awareness. Instruction is generally four to six months for one hour a day. Studies have shown that the program improves students’ word-reading accuracy and fluency.[1050] However, for many students, a less intensive program targeting these skills was as successful.[1051] Thus, the LiPS® program appears best as a tier 3 intervention for students who do not make adequate progress with a good tier 2 program. These students need more intensive, targeted instruction to identify and hear individual sounds in words, to then better learn sound-letter connections and blending these to sound out words. Like all programs, it should be used in its entirely rather than in individual pieces taken out of context.

Online programs and resources

Some boards use online programs that either have research evidence or are aligned with the approaches outlined in this report. The inquiry does not recommend online programs in place of teacher-led classroom instruction and tiered interventions. Rather, school boards should explore how online programs can be used to enhance effective, teacher-led instruction and interventions in tiers 1 through 3.

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABRA (A Balanced Reading Approach for Children and Designed to Achieve Best Results for All)[1052] is a Canadian online program that can help pre-school to early elementary school-age children develop phonemic awareness, phonics and word-reading skills. It includes first- and second-language instruction in both English and French. The program is free of charge. School boards can also download assessment resources and toolkits to their servers free of charge. This program can be considered a supplement to explicit classroom instruction in foundational word-reading skills that offers students practice and support.

The program was developed through a multi-university initiative and has been studied in Canada and internationally (for example, Australia, Kenya), to explore its impact on children’s reading.[1053] When used regularly in the classroom, students perform at a higher level on several reading-related skills compared to students who received only typical classroom instruction.[1054]

This has been observed consistently across cultural backgrounds and geographic locations where studies took place.[1055] For example, in Australia’s Northern Territory, researchers delivered the program to 164 children and compared the results to a control group of 148 children who received regular instruction. The total sample included 28% Indigenous students. Results showed that all students in the intervention group made significant gains in phonological awareness and phoneme-grapheme knowledge over the control group. Indigenous students gained significantly more per hour of instruction than non-Indigenous students in phonological awareness and early literacy skills.[1056]

PlayRoly

PlayRoly is a play-based online program developed in British Columbia.[1057] The program is for children who are three to five years old and is designed to strengthen phonological awareness skills. All the lessons are available at no cost to educators and parents.

Parker Phonics

The book Reading Instruction and Phonics: Theory and Practice for Teachers[1058] includes a phonics scope and sequence program. The book is online and can be downloaded for free.

Lexia® Core 5® Reading

Lexia® Core 5® Reading is a computer-based intervention to supplement regular classroom instruction and support skill development in the five areas of reading instruction identified by the National Reading Panel. It uses web-based and offline materials to help pre-Kindergarten to Grade 5 students develop phonics, decoding, word reading, fluency and reading comprehension.

There is some evidence to support the use of this program to improve skills in phonics and reading comprehension for students in Kindergarten to Grade 5 who have reading difficulties.[1059] The program may also work to support word reading for multilingual students who are learning English at the same time as they are learning the curriculum.[1060] Computer-based interventions such as Lexia® work best as a supplement to tier 1 instruction or tier 2 interventions, always under the direction of a trained teacher.

Ontario’s approach to reading interventions

Ontario’s tiered approach

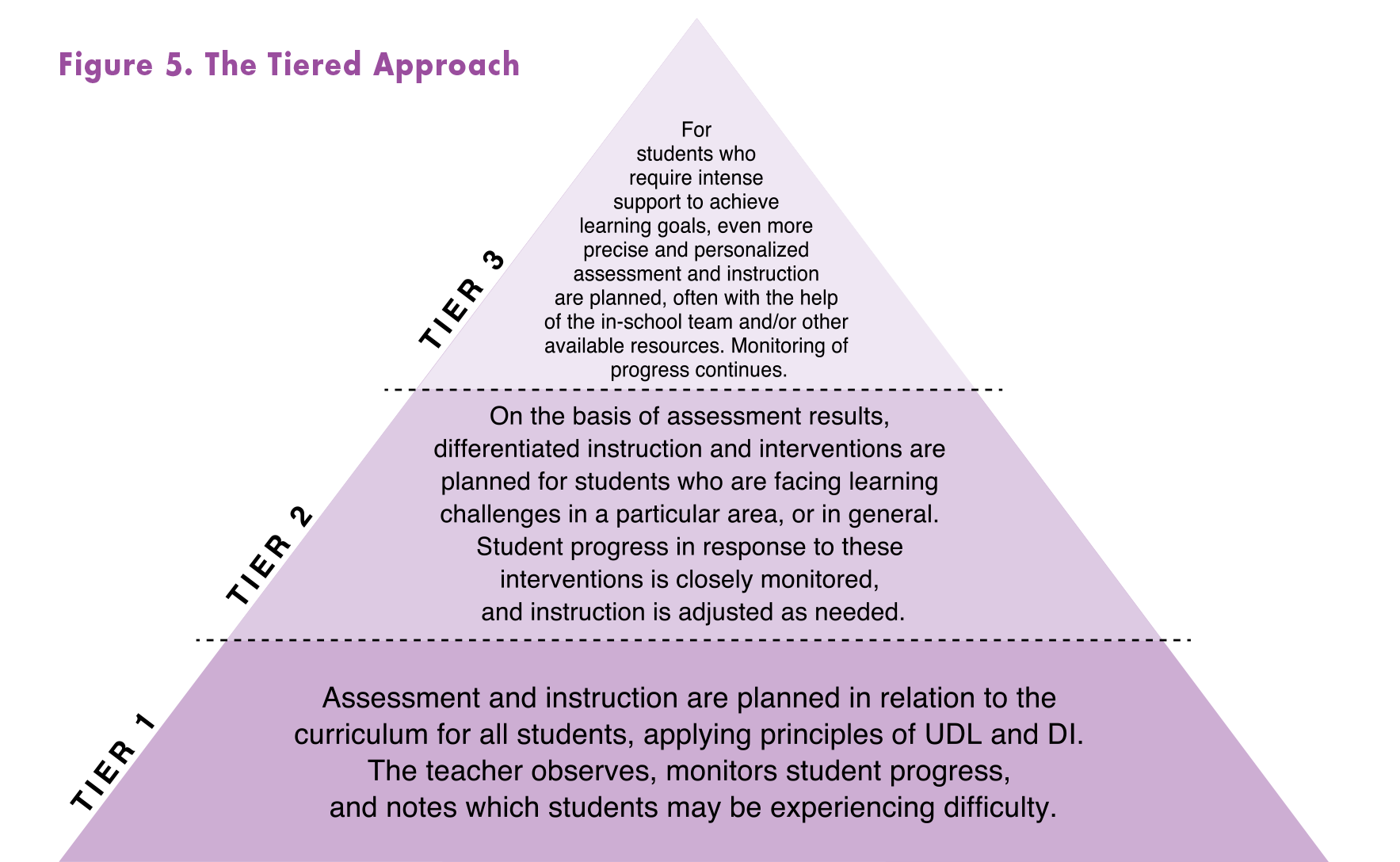

In Ontario, the Ministry recommends[1061] but does not mandate a tiered approach. It defines a tiered approach as “a systematic approach to providing high-quality, evidence-based assessment and instruction and appropriate interventions that respond to students’ individual needs.”[1062] This approach is also known as RTI/MTSS.[1063] The figure below is an excerpt from one of the Ministry’s resource guides:

Figure 5: The Ministry of Education’s tiered approach model

The Ministry does not provide any detail on how to implement a tiered approach to prevent reading difficulties in each tier.

For RTI/MTSS delivery to be effective in maximizing all students’ academic achievement within an inclusive education system, all the critical components need to be evidence-based, implemented properly, and have all the necessary resources – financial and otherwise.

A tiered approach will not be effective if the curriculum outcomes are not aligned with evidence-driven classroom instruction (tier 1) or if tier 2 and 3 interventions are not evidence-based. It will also likely not be effective without other mandated elements such as universal screening, progress monitoring, data collection and standardized decision-making procedures.

Classroom instruction (tier 1) is not currently aligned with evidence-based instruction for foundational word-reading skills. As a result, far too many students need early and later interventions, and this is particularly evident in schools that serve communities at higher risk for word-reading difficulties (for example, more students from low-income families).[1064] Some of the early and later interventions being used are not evidence-based.

It is not enough to suggest a tiered approach. The Ministry should mandate effective implementation of RTI/MTSS frameworks across Ontario.

None of the Ministry guides outline what interventions are evidence-based. While in 2021, the Ministry provided examples of intervention programs in its Transfer Payment Agreement (TPA) to school boards for purchasing reading interventions, only suggested guidelines were included.

In its inquiry submission, the Physicians of Ontario Neurodevelopmental Advocacy noted the necessity of mandating evidence-based interventions:

A tiered approach to intervention needs to be required (not just suggested as in PPM 8), with early implementation of Direct Instruction using evidence based tools that are available in all schools. The Ministry of Education should fund these programs directly so schools cannot claim they are too expensive to implement.

Standards on the use of reading interventions

Schools use many different reading interventions. Standardizing interventions would lead to more equitable outcomes and would likely result in cost savings over time.

The Ministry does not mandate any approaches to intervening when students are not developing foundational word-reading accuracy and fluency. School boards determine which reading intervention to use, which grades to provide the interventions, eligibility criteria, and if and how to track student progress. Sometimes boards delegate this responsibility to individual schools.

The inquiry boards reported having at least 16 different commercial interventions, only five of which were evidence-based. However, two of these evidence-based interventions were seldom used. There were six board-developed interventions, but none of them had been rigorously evaluated or included the scope of all skills needed to address early or later word-reading difficulties.

Some inquiry boards said they do not have the resources or capacity to always research which intervention is effective. Very few boards could produce sound research on the effectiveness of interventions they were offering, or report how an intervention they used was aligned with the science of effective reading instruction. This is why knowing the research on effective reading instruction and interventions is a critical prerequisite. Without this knowledge, system leaders and personnel are not in a position to evaluate a program.

Many inquiry schools boards wanted direction from the Ministry on which reading interventions to use, and thought it would be more efficient for the Ministry to purchase licenses for evidence-based interventions. One board said “not all boards are rowing the boat in the same direction.” This approach would likely increase the effectiveness of teaching more students to read, and result in financial savings based on economies of scale.

Educators who completed an inquiry survey reported that school boards or schools often do not have the funds to buy interventions or train staff to deliver them. This is one of the essential components of effective RTI/MTSS implementation. A board literacy consultant said:

There are so many different reading interventions available. More direction is needed in terms of which intervention is best for [whom].The Ministry should also provide more funding specifically for reading intervention.

When essential programs are not standardized across the province, it creates the potential for inequality. One survey respondent, a psychologist, said:

…A systematic and intensive phonics program is needed in ALL schools across the province. The availability of this type of program should NOT be dependent on a school's discretionary budget. This is incredibly inequitable as some schools receive much more money in fundraising efforts (parent donations) than others.

2016–2020 Reading pilot project

In 2016, the Ministry provided funding for the LD Intensive Reading Pilot Board Project in eight English-language public and Catholic district school boards. Originally planned for three years, the Ministry continued funding the pilots for the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 school years.[1065] The pilot was intended to increase the availability and responsiveness of supports for students with learning disabilities in reading. While this is a worthy goal, it is not clear if the pilot also included the goal of increasing academic achievement and outcomes in reading and other academic subjects.

The eight pilot boards were Greater-Essex, London Catholic, Rainbow, Sudbury Catholic, Thames Valley, Waterloo Catholic, Waterloo Region and Windsor-Essex.

These boards selected students who were at risk for or already identified with an LD exceptionality with reading challenges to take part. The pilot included supports to match those provided at the three English Provincial Demonstration Schools for students with learning disabilities in Ontario. These supports included the Empower™ Reading Program (Empower™), a systematic and intensive reading intervention program, Lexia® Core 5®, a technology-based literacy program and social-emotional supports.

The Ministry’s pilot project found that, overall, Empower™ had some positive effects on some aspects of foundational skills for students. Dr. Rhonda Martinussen, a psychologist from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), led the external research team that evaluated the project. Although the pilot studied the Empower™ program, the findings were expected to also inform board practices in implementing any tier 2 or tier 3 reading intervention. The goal of the research was to enable boards to implement a range of evidence-based reading interventions to meet the needs of students with learning disabilities in developing reading skills.

The research team’s 2020 final report discusses factors that influence how successfully Empower™ is implemented. Factors included how often lessons were given, interruptions to learning, staff training and collaboration with homeroom teachers. Boards also reported that student selection criteria was an important area of focus including determining need and fit with the program.

The research team reported a positive response to the pilot activities in terms of principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of student engagement and gains in their learning. Interviews with principals and teachers reported an encouraging response to the intervention program because of the positive effects on students’ reading skills, self-confidence, and perception of themselves as readers.

Analysis of students’ pre- and post-assessment measures was reported for students who had completed at least a large proportion of the program.[1066] The 2020 Ministry report showed an increase in participants’ core phonics skills (for example, reading words with short vowels and with consonant blends; reading words with more complex spelling patterns, such as r-controlled vowels, long-vowel spellings, low-frequency spellings, and reading multisyllabic words).

As well, the mean scores on standardized tests improved for word- and non-word-reading accuracy and fluency, and reading comprehension (see Table 21). Mean standard scores on the non-word-reading subtest came into the average range. However, the sample size of 70–80 students was not high and only 41% of these students received all 110 hours of the Empower™ program.

Figure 6: Reading level at program start and growth

Grade 2 students made larger standard score gains in non-word-reading (word attack subtest) than students in Grades 3 and 4 (see Figure 5). This is consistent with some past research showing younger students make larger gains with Empower™.[1067]

As can be seen in Figure 6, the participants in each grade level made gains and of similar magnitudes, on standardized word-reading scores. These mean scores on word-reading accuracy, however, did not come within the average range. The report did not present the number of students altogether or in each grade who came into the average range for each different measure. This is data that school boards and the Ministry should collect when implementing Empower™ and other reading intervention programs.

Figure 7: Gains in decoding by grade in Ministry pilot project[1068]

Figure 8: Gains in sight words by grade in the Ministry pilot project[1069]

2021 Transfer Payment Agreement (TPA)

The Ministry provided additional funding to school boards to purchase reading intervention programs in Winter 2021. The Ministry created a TPA that outlines guidance on selecting appropriate interventions. This is a good start and provides more detailed guidance than any other Ministry document, including PPMs, resources and guides. The Ministry provided an overview of the tiered approach and related reading interventions for each tier. For example:

- Tier 1: programs are delivered in the class; the instruction is targeted to address a specific gap that has been identified through assessment

- Tier 2: higher intensity and may be delivered by a classroom teacher or a special education teacher, and it is usually every day or close to every day for 20 to 40 minutes in general, could be more or less

- Tier 3: delivered by a trained special education teacher with a very small group or an individual student, consistently every day and for a longer period of time each day than in tier 2 (for example, 60 minutes, and ideally in addition to the regular language class), and using a high-intensity evidence-based program.

The TPA provides examples of literacy programs that meet the core literacy skills outlined in the document (phonemic awareness, phonics, word reading, reading fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension). The listed examples are SRA’s Early Intervention in Reading, Corrective Reading, Reading Mastery, Empower™, Jolly Phonics, Kindergarten Peer-Assisted learning Strategies (K-PALS) and PALS.

Although the document acknowledges this is not an exhaustive list, it is important to include more tier 1 whole-class reading programs such as SRA Open Court Foundational Skills and Wilson Fundations®.

School Board approaches to reading interventions

Overall approach

All eight inquiry school boards reported using an RTI/MTSS framework to address reading achievement and provide interventions for struggling students. However, boards are not structuring tiered interventions in way that is consistent with effectively implementing RTI/MTSS systems.

The inquiry found concerns with critical aspects of how boards are choosing and implementing interventions. Many interventions are not evidence-based. When schools do have evidence-based interventions, they are not available in the earliest grades where they are most effective in fully addressing word-reading accuracy, and word- and text-reading fluency.

Many students face barriers to accessing effective interventions. In some cases, boards prioritize interventions for students with a learning disability diagnosis, which can be difficult to receive, or get in a timely way, unless obtained privately at significant cost. Other problematic criteria include requiring students to have average to above-average intelligence and/or no other disability (such as ADHD, ASD, MID). These entry requirements are based on a mistaken belief that interventions will only be effective or be more effective for these students, which research has consistently contradicted.[1070]

All of these barriers can result in systemic discrimination against groups of students who need intensive interventions in reading. The exclusionary criteria are not appropriate measures for decisions about whether a student will respond to a reading intervention.[1071] See section 12, Professional assessments.

School boards sometimes only offer interventions to students who are a specified number of grades or years behind in reading. This is not based on science or sound use of statistical reasoning, and will leave many students behind. A child in Grade 1 or 2 who is a year or half-year behind their grade-level peers needs immediate interventions.

Interventions are not provided to all students who need them. The inquiry found that resources for interventions are generally not distributed to schools that may be deemed higher priority in terms of the number of students at risk for or with reading difficulties. The inquiry could not determine if enough training and support has been provided to educators implementing the various interventions, which is important to how successful a given intervention will be.

Boards are not adequately monitoring individual student progress and the effectiveness of intervention programs. This data is needed to inform decisions about individual students, and to make data-driven decisions at the board level, on which intervention programs are leading to successful outcomes and in which schools. For example, a program that was promising may not be having good effects across most schools, or a family of schools may be getting exceptional results with a certain intervention and could offer lessons about implementation procedures for the board or province.

Each inquiry board reported that the goal of their RTI/MTSS is to effectively meet the instructional needs of about 80–90% of students through tier 1 instruction; leaving 10–20% of students requiring tier 2 interventions, and 5–10% of students who will require tier 3 intervention.

In practice, many more students require tier 2 and 3 interventions in Ontario school boards. The current approach to reading instruction and intervention in boards is not effective and conflicts with boards’ stated goals of meeting most students’ reading instruction needs in tier 1, so only a very small proportion of students (5–10%) will need tier 2 interventions. The current set-up wastes valuable time and jeopardizes the critical period when many future reading difficulties could be prevented.[1072]

This is a direct result of the ineffective approaches in the classroom that are based on the Ministry’s curriculum and instructional guidelines and implemented by boards. There is an absence of, and even an avoidance of, direct and systematic phonics and decoding instruction. At tier 2, many ineffective interventions are the first response. With ineffective instruction and tier 2 interventions, the boards are falling far short of their goals for the percentage of students who will need each successive level of tiered interventions.

The Ministry promotes whole language and balanced literacy philosophies and approaches in its curriculum and teaching guideline documents. These documents promote an inaccurate view of reading development and instruction. See section 8, Curriculum and instruction. Many of the early intervention programs used by schools also follow these ineffective approaches to teaching reading (using cues to deduce the spoken form of unknown written words in text) and/or largely focus on phonological awareness to the exclusion of other critical foundational reading skills. Thus, when children with difficulties in word reading are placed in tier 2 interventions, they do not receive the needed instruction in foundational word-reading skills.

Evidence on how to teach all students to learn to read is highly consistent with OSLA’s submission to the inquiry that schools must use “systematic, direct instruction with lots of practice over time and specific feedback, because reading skills are too important for children to have to infer what they are supposed to learn.”

The results from the Grades 3 and 6 EQAO reading assessments for students overall and for students with special education needs supports the finding that school boards’ current approaches to reading instruction and intervention are not effective. More than half of students with special education needs in Grade 3, and almost half in Grade 6, failed to meet the provincial standard.[1073]

One school board also noted that about 32% of its Kindergarten and Grade 1 students were at risk for reading difficulties, consistent with a general estimate in most school boards of about 30%. In 2018–2019, 74% of all Grade 3 students in Ontario met the provincial standard for the EQAO reading assessment, but only 62% of these students did so unassisted (without scribing or assistive technology). Only 8% of Grade 3 students with IEPs met the standard without assistive technology.[1074] This data should make Ontario school boards question whether their early interventions have been effective. If interventions do not vastly reduce the number of students at risk in an area, it is an indication that those interventions have not been successful. See section 5, How Ontario students are performing.

The materials provided by the school boards show a need for increased tier 3 interventions for students who struggle with word-reading skills – implying that earlier tier 1 instruction and tier 2 interventions have not been effective. With so many students in need of reading interventions beyond classroom instruction, it is not surprising that the resources for tier 2 and tier 3 interventions are limited. Inquiry boards reported having far too many students needing interventions, overwhelming their ability to provide tiered supports beyond the classroom. However, if classroom instruction (tier 1) is evidence-based, it will relieve the financial pressure on the system as fewer students will need tier 2 and tier 3 interventions.[1075] This “ounce of prevention” is currently absent in school boards.

Students are also not receiving interventions early enough, and interventions are certainly not effective or evidence-based. In the inquiry survey for students and parents, respondents across Ontario reported that only 33% of students received reading interventions before Grade 2. The most commonly reported time students received interventions was in Grade 3. Most students (62%) received a reading intervention program in Grade 3 or above.

Table 21: Grade level students received intervention (student/parent survey)

|

Grade |

Percentage of students |

Number of students |

|

Kindergarten Year 1 |

1% |

8 |

|

Kindergarten Year 2 |

2% |

25 |

|

Grade 1 |

11% |

128 |

|

Grade 2 |

19% |

223 |

|

Grade 3 |

23% |

265 |

|

Grade 4 |

16% |

186 |

|

Grade 5 |

11% |

125 |

|

Grade 6 |

7% |

85 |

|

Grade 7 |

4% |

45 |

|

Grade 8 |

1% |

34 |

|

Grade 9 |

1.5% |

17 |

|

Grade 10 |

0.5% |

4 |

|

Grade 11 |

<0.5% |

1 |

|

Grade 12 |

<0.5% |

2 |

|

Unknown |

1% |

9 |

|

Total |

|

1,157 |

Tier 2 interventions

Most inquiry boards do not have evidence-based early reading interventions and do not have procedures to effectively deliver them to the young students who need them. Students who need interventions the most are often not receiving them. In most boards, Kindergarten and Grade 1 students with or at risk for word-reading disabilities are the least likely to have access to evidence-based interventions.

Although many inquiry boards implement some intervention in Kindergarten in phonological awareness and/or sound-letter knowledge, these are most often board-developed. They do not adequately teach necessary skills, such as those taught in a synthetic phonics program focused on word decoding, and word-reading accuracy and fluency.

The inquiry boards’ most frequent early interventions follow similar instruction strategies used in the classroom, but delivered in smaller groups. These often include programs based on guided reading and supplemental “word work,” rather than the targeted and systematic programs required for students to progress in foundational word-reading skills. Early interventions need to focus on explicit and systematic instruction in grapheme-phoneme correspondences, and on how students use these to sound out words (blending part of phonemic awareness) and to spell words (segmenting part of phonemic awareness). In other words, this involves using a synthetic phonics program that teaches all the necessary skills that students need to decode and spell.

School boards are using a combination of commercially available reading interventions such as Levelled Literacy Intervention (LLI) and Reading Recovery®, and some board-developed approaches. These approaches are ineffective and insufficient, based on both the body of research on effective early interventions and the boards’ own outcome data on early reading.

Boards use commercial reading interventions to determine if students need further interventions. If a student is struggling to learn to read, the school will increase guided reading in the classroom (tier 1). If the student still struggles, the school will provide extra reading support, such as LLI, or often, “extra reading support” which is vaguely defined (tier 2). If the student is still not progressing, the school will provide SRA Reading Mastery, SRA Corrective Reading or Empower™ (defined by school boards as tier 3). This approach means students often endure years of ineffective supports in tier 1 and tier 2, before maybe being offered an evidence-based intervention in Grades 3 to 4 or later. We know interventions in these later grades need to be more time-consuming, more intense in the breakdown of all component parts of foundational reading skills, and have more teacher-directed, scaffolded practice and review. Even then, these later interventions will not fully address gaps in reading achievement for as many students as would early intervention.

Some of the inquiry boards recognize the foundational skills that need to be taught as part of reading instruction, and provide board-developed early intervention programs. The board-developed approaches target some skills found in evidence-based programs, like phonological or phonemic awareness, and some aspects of letter-sound work. However, these programs do not deliver a thorough, systematic, explicit program in phonics instruction toward building decoding and word-reading and spelling skills. Isolated phonological awareness work is not enough to catch students up or to prevent later word-reading difficulties.

In these board-developed intervention approaches, students (primarily in Kindergarten) who scored low on a screener enter a program working with a teacher, speech-language pathologist (SLP) or another educator, in a small group for a defined period of time. The focus of these skills is most often on phonological awareness, and may include some letter-sound teaching and other aspects of oral language.

Boards have not established that these in-house interventions, some more formalized than others, are effective for addressing and preventing future word-reading difficulties.

Half of the inquiry boards reported using the Lexia® Core 5® reading program as a stand-alone intervention or as a classroom or intervention supplement. There were differences in how teachers supervised the use of this computer-based intervention. Computer-based interventions should not be substituted for effective teacher-led interventions. They should be used under the supervision and direction of a teacher and as a supplement to a teacher-led program. The boards did not provide clear reports to show the effectiveness of Lexia® Core 5®.

Tier 3 interventions

Ontario school boards need to use intensive programs as the first line of intervention when students are behind their same-age peers in critical reading skills. Boards are withholding these interventions and only using them after ineffective tier 2 approaches have failed.

Some boards use evidence-based interventions such as SRA Reading Mastery, Corrective Reading or Empower™. However, many boards require proof that students have had a prior literacy intervention that did not work before enrolling them in further (usually evidence-based) interventions. In many of the inquiry school boards, students only receive systematic and explicit structured literacy programs in tier 3, and for some boards, this may not happen until as late as Grade 4, 5 or 6.

Generally, these intervention programs are not available in the earliest grades (Kindergarten – Grade 1 ideally, or in Grade 2) when they will be most effective. When they are provided early, they are only provided in a small sample of schools as part of the Ministry’s reading pilot project or the board’s own pilot. However, one board, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic, noted that it makes SRA Reading Mastery, an evidence-based program, available to Kindergarten and Grade 1 students.

The inquiry boards reported important differences in how they implement evidence-based tier 3 programs. These differences may undermine effectiveness in some cases. Students have varying access to what boards consider tier 3, focused interventions such as Empower™ and SRA interventions. While several boards deliver these to students in Grades 2 through high school, other boards deliver the interventions only to students in higher grades (for example, Grades 6–8). This variation was particularly significant for delivering Empower™, while SRA Reading Mastery and Corrective Reading served a broader grade range among the school boards.

Even when boards reported that interventions were available for a broader grade range, the focus was on delivering the program to students in Grades 4 and above. Hamilton-Wentworth, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic and London Catholic were exceptions to this general rule. Hamilton-Wentworth had a high proportion of Grade 2 students in Empower™ and both Simcoe Muskoka Catholic and London Catholic provided Reading Mastery in earlier grades as part of a pilot project to target younger students.

Availability

Effective programs are not available for all students who need them. Access to reading interventions that work well varies dramatically by board. Often, the non-evidence-based interventions are the ones most widely available.

The availability of interventions was inconsistent between and within school boards. It is difficult to compare availability between boards because every board has a distinct way of providing and tracking interventions.

Some boards purchase reading interventions or develop their own interventions and directly provide them to schools. Other boards leave the choice of interventions to individual schools. This can lead to disparity between which schools get effective interventions and which do not. Also, a board’s decision can mean most students within that board will not have access to effective early reading intervention.

Boards reported that both commercial programs and board-developed kits were available to teachers. However, there was no accountability for what programs were implemented or how schools and teachers were guided to use effective programs and at critical periods of time. One board noted that schools may have the kits available but that does not mean that they are being used. Boards reported that teachers view them as an optional resource.

School boards reported the number of schools that had access to a given intervention – but had less information about whether schools deliver the program or how many students were enrolled. Many boards reported that availability of interventions was based on “the needs of individual students” or “school data,” but were less clear about the actual data that informed decision-making. Without universal early screening, boards are not in a position to assess the needs of individual students, and the decision-making processes appear ill-defined. See section 9, Early screening.

Inquiry survey respondents reported very limited spots for evidence-based interventions at schools. Some student and parent respondents reported having to change schools to access a “reading intervention hub.” Most school boards also reported that some schools either had LLI or Empower™. This means that some schools do not have any evidence-based interventions. This is inequitable, as every student should have access to effective reading interventions without having to change schools or school boards, go to a Provincial Demonstration school or pay for private tutoring.

In inquiry surveys, educators expressed concerns about reading interventions and the procedures guiding their selection and delivery. They said there are no standards for reading interventions and many factors inform decisions about which programs are delivered, such as special education teachers’ subjective preferences, time, budget and available trained staff. These school-level operational factors should not drive decisions that result in inadequate and inequitable access. One psychologist said:

Many schools don't have access to evidence-based reading programs or available teaching staff to offer the programs, so they select what they have (e.g., often LLI) and whichever special education teacher is trained and available to offer it.

Even when boards deliver evidence-based interventions, the full program, including the early interventions, may not be available in all schools. In some boards, only a relatively small percentage of schools were delivering early interventions (for example, only 30–40% of schools). One board did not have any evidence-based interventions for students until Grade 5.

Most boards did not have a system to allocate resources to communities or schools that may be deemed higher priority in terms of high numbers of students at risk for or with reading difficulties. Hamilton-Wentworth did report allocating more reading supports to schools based on national census data on unemployment rate, lone-parent families, recent immigration, low household education level and low income (less than $30,000). However, without guidelines for choosing and delivering effective interventions, it is hard to judge whether allocating more resources would translate into more effective classroom programs and interventions.

All students who do not have skills in the solidly average range compared to same-age peers on measures of word-reading accuracy and fluency need effective interventions. Tiered interventions should be distributed based on school needs, so that all students have access to effective classroom instruction and interventions.

Student selection criteria

Generally, the inquiry boards did not have clear procedures to identify students and enroll them in early interventions. Broad discretion and unclear processes are susceptible to bias and inconsistent implementation. School-level decision-making can be driven by pressures due to finite school supports and resources.

Teachers and psychologists suggested this in the inquiry surveys. For example, one teacher said: “I think there is a bias or implicit belief that some students will not learn to read.” This raises alarming equity issues, which have been discussed throughout this report.

One psychologist, responding to a survey question asking how decisions are made about which students receive reading interventions, said they “suspected this is done rather unsystematically.” Another professional said:

The disconnect here is the funding. We can say all students should, and do deserve, reading [interventions]…100% of the time, but funding just won’t allow this…that means only the students experiencing the worst difficulties, or with parent advocates, will be referred to very intense reading speciality programs in schools that require small class sizes, [one-on-one], etc.

Other teachers said it depends on “how much the parents push.” Parents reported they did not know about reading intervention programs, and when they found out about them, it was either too late as an option for their child or it took significant parental advocacy to get their child into the program.

Most school boards rely partly on unreliable or invalid assessments to determine who receives interventions. These assessments look at students’ book-reading levels at certain points in each grade. Examples are PM Benchmarks and Benchmark Assessment System (BAS). These are often the primary measures, along with teacher observations, informing decisions about the need for an intervention and placement into a program. Teacher professional development materials often stress assessments such as running records to identify students who need additional interventions.

The inquiry found many problems with these assessment systems. Book-reading assessment strategies can obscure word-level reading difficulties, particularly in the primary grades. These approaches confuse a student’s decoding and word-reading skills with their language comprehension. They are inadequate measures of foundational word-reading skills, as students may and have indeed been taught to use their oral language skills and pictures to guess at unknown words on the page.[1076]

Word-focused programs for older students set out clearer guidelines for program entry. For example, Ottawa-Carleton’s materials noted that “decoding” is the primary deficit for entry into the Empower™ program. Still, even for older students, access to interventions were often based on book-reading-level assessments, rather than on word-reading skills.

As noted in Section 8, Curriculum and instruction, the Simple View of Reading provides a framework for thinking about the two broad components that determine students’ reading comprehension. Assessments need to examine each component independently, to place students in appropriate interventions. See section 9, Early screening for a discussion of skills that need to be assessed in Kindergarten to Grade 2. As students move beyond Grade 2, word-reading accuracy and fluency should be measured to make decisions about appropriate placements in interventions.

Students who struggle with both word reading and language comprehension need targeted, intensive word-reading interventions. As well, they need effective programing for any oral language weaknesses. It is critical to make sure effective word-reading interventions are not delayed for these students because of oral language weaknesses.

Student eligibility requirements

Although most boards do not require a diagnosis of a learning disability for entry into interventions, there were variations. One board required students to have a diagnosis to be eligible for Empower™. Other boards reported prioritizing students with a diagnosis. Student/parent survey respondents from many boards across Ontario said that having a diagnosis was needed or helped get interventions.

Requiring a learning disability diagnosis is not necessary and can create equity issues. When criteria for a learning disability require at least average intelligence or a discrepancy between intelligence and achievement for diagnosing a learning disability, this raises the potential for systemic discrimination. See section 12, Professional assessments.

Also, some boards said or implied that only students with particular qualities, such as certain cognitive or “LD-like” profiles, benefit from Empower™. Research has shown that IQ, cognitive abilities or cognitive processing strengths and weaknesses do not predict a student’s response to reading interventions.[1077]

School boards need to remove these requirements from eligibility criteria. Also, boards must examine if, in practice, certain groups are being unconsciously excluded from interventions. The OSLA recommends that the education system must:

Assess for bias in processes to select students for reading interventions and ensure access for students from equity seeking groups, especially members of intersecting Code-protected groups…and ensure access to reading interventions for students with a range of learning needs…and those with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Some boards required a student to be a specified number of grades or years behind in reading. For example, one board required that the student be two years behind in reading and another required that the student be “significantly behind in reading.”

Grade- or age-equivalent scores should not be used to determine entry into effective intervention programs. These scores are not interval levels of measurement. In other words, the difference between each grade- or age-equivalent score is not equal or comparable. The example below serves to illustrate this fallacy.

Consider a student in mid-Grade 2 who scored the same on a word-reading test as the average score of children at the beginning or even the middle of Grade 1. School boards that use grade-equivalent scores would consider this student one or 1.5 years behind. A student in mid-Grade 8 who received a grade-equivalent score of mid-Grade 6 on a word-reading test would be considered two years behind. If the board uses a “two years behind” criterion, the Grade 2 student would not be eligible for an intervention program despite being far below same-age peers and struggling in word-reading accuracy. The increase in word-reading accuracy between Grades 6 and 8 is not as vast, and the Grade 8 student would not be struggling with word-reading skills to the same extent as the Grade 2 student. This is why percentile or standard scores should be used.

Boards should use standardized scores at each grade level and provide interventions for students below a given criteria (such as at or below the 25th percentile on word-reading accuracy and/or fluency). Similarly, the requirement that students are “significantly” below grade level in reading is not clear, and may be interpreted differently across schools, affecting who will get an intervention.

Requiring students to be a certain numbers of years behind on assessments violates the scientific properties of these measurements and sets up a “wait to fail” system of intervention delivery.

Also, most school boards required that multilingual students who are learning English at the same time as they are learning the curriculum have at least two years of English language instruction before considering them for an intervention. This approach is not supported by research and delays timely intervention. Multilingual students should receive interventions as soon as the need arises.[1078]

A few school boards had positive elements in their approach to selecting students for interventions. Hamilton-Wentworth reported that they provide equitable access to all students who require Empower™. Their process for selecting candidates explicitly includes students with MID or who have a “slow learner profile” as well as non-identified students with and without IEPs.

A few boards recognized that early intervention must be provided immediately without requiring psychoeducational assessments. For example, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic used funds provided for professional assessments by the Ministry to purchase SRA interventions. The board noted: “It made a lot of sense to increase intervention levels and possibly decrease assessment in the longer term. We are trying to do phonemic and phonics instruction early on without waiting for assessment.”

Monitoring student progress

Ontario boards do not currently have a consistent system to measure students’ progress or response to an intervention, or to monitor long-term effects. School boards should collect valid and reliable data on students’ immediate and long-term outcomes, to inform their decisions about individual student programming and efforts to evaluate program effectiveness.

Boards need standardized measures to judge if an intervention has been successful for a student. Success means improving outcome scores to the average range on measures of reading accuracy, fluency and comprehension. If a student has not come into the average range, then the school must provide further intervention and programming. Monitoring progress can also tell educators about the nature of a student’s continuing difficulties, to help inform next steps.

Boards often reported using students’ book-reading levels to examine the effectiveness of an intervention. This is problematic for gauging progress in any intervention, including guided reading approaches (for example, Reading Recovery®, LLI). Book-level systems do not measure what aspects of reading are contributing to the students’ difficulties in reading and understanding texts. For example, a student could increase by many levels, and may even reach the benchmark for their grade by increasing their oral prediction skills without also increasing their word-reading and decoding skills. However, word-reading and related decoding skills must increase to improve the student’s reading trajectory.

Another problem with using these assessment systems is that each increase in level is not a meaningful unit and cannot be reliably interpreted. Book-reading levels are not interval units of measurement (just as grade-equivalent scores are not). This means that the “amount of improvement” between each level is not comparable. A student moving from level B to level C is not comparable to that student later moving, or an older student moving, from level G to level 1.

Similarly, a three-level increase by students from early to mid-Grade 1 is not comparable to a three-level increase for students in early to mid-Grades 2, 3 or 4. Yet, many boards judge individual student success in a program and the program’s overall effectiveness on reports of students’ book-reading levels and increases in those levels. Some boards reported the number of students meeting a grade-level benchmark alongside the average number of units of increase across students. These methods are not adequate to judge student progress.

Most boards do not currently use standardized measures of reading.[1079] They use program-specific assessments designed to test for the skills taught during a given intervention. These assessments should be supplemented with standardized reading measures to evaluate student progress and make further programming decisions. For example, the Empower™ Reading Decoding and Spelling programs have a pre- and post-test assessment for five program-specific measures.[1080] These measures alone do not help with decisions about how much a student has improved on generalized word-reading accuracy and fluency, or about whether these skills are now within the solidly average range.[1081]

Hamilton-Wentworth has a good foundation for monitoring progress. It tests students before and after receiving the Empower™ program. The board includes standardized measures of word-reading accuracy (a word identification subtest), non-word-reading accuracy (a word attack subtest) and reading comprehension (passage comprehension subtest).

Adding in word-reading efficiency and/or text-reading fluency measures would complete this battery of monitoring. These measures are each very brief subtests that can be given by a range of school personnel, and provide necessary information to make decisions on individual students. Other boards should adopt a similar approach to Hamilton-Wentworth and add tests to measure fluency. This would be useful to inform decisions about individual students and for program evaluation across all interventions.

These standardized reading measures and decision-making processes are necessary to judge a student’s response to the full range of school-based interventions, including SRA Reading Mastery, SRA Corrective Reading, and Lexia® Core 5®.

Students in early reading interventions will also need standardized measures of phonemic awareness, sound-letter fluency, and reading and decoding.

Program evaluation

Most boards do not track outcomes from interventions at a system level.[1082] Many of the same issues with student progress monitoring also apply to the how school boards examine program effectiveness.

Boards examined program effectiveness in a variety of different ways – some more valid than others. As noted earlier, book-reading assessments are not valid or reliable.

Some boards used these approaches:

- Comparing pre- and post-intervention book-reading levels

- Assessing whether students improved on one or more measures, sometimes specific to the intervention program

- Comparing students’ improvement in an intervention program with a group of students who did not have the intervention.

Although these approaches are a good first step, they are not enough to evaluate an intervention program. They do not tell boards if foundational word-reading skills were addressed to support, and correct, the trajectory for continued reading development.