Dr. Scot Wortley

Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies

University of Toronto

Submitted to the Ontario Human Rights Commission September 2021

ISBN: 978-1-4868-5400-4 (Print), 978-1-4868-5401-1 (PDF), © 2021, Government of Ontario

Introduction

Canada is one of the world’s most active immigrant-receiving nations, and has received international praise for its official policies of multiculturalism and racial inclusion. An argument could be made that Canada’s reputation for racial tolerance is well deserved – especially when race relations in Canada are compared to the situations in the United States and some parts of Europe. A closer examination of the historical record, however, reveals that racial bias and discrimination have been serious issues within Canadian society – particularly with respect to the operation of criminal justice system. Indeed, a number of scholars have documented that allegations of racial bias with respect to law creation, policing, the criminal courts and corrections have existed in Canada since before confederation (see for example Perry 2011; Walker 2010; Henry and Tator 2005; Chan and Mirchandi 2001; Mosher 1998). For at least the past 60 years, racial bias with respect to police stop, question and search behaviours – and the official documentation of these encounters through the practice of carding or street checks – has emerged as a particularly controversial issue. Canada’s Black, Indigenous and Muslim communities have been especially vocal in their complaints about what has come to be known as “racial profiling” or “racially biased policing.”

Historically, allegations of racial bias have been denied – often vehemently – by Canada’s major police services and police associations (see Tanovich 2006; Tator and Henry 2006; Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011a). Ultimately, some high-ranking police officials, including former Toronto Police Chief Bill Blair, publicly admitted that racially biased policing may be an isolated problem within some communities or among some officers. However, police leaders have rarely discussed the consequences that systemic, racially biased police practices have had on racialized communities. Furthermore, until recently, few police services committed to the long-term study of this phenomenon (see James 2005).

This may be changing. For example, in December 2018, following allegations of anti-Black racism in law enforcement, former TPS Chief Mark Saunders acknowledged that anti-Black racism is a “reality” and that public criticism has been “more than fair” (CBC News 2018). Similarly, in August 2020, TPS Interim Chief Jim Ramer recognized racial bias as an issue and stated that one of his top priorities would be to identify and eliminate systemic anti-Black racism in the Toronto Police Service (Goodfield 2020). Finally, the Toronto Police Services Board recently adopted a policy that will enable the collection of race-based data on police-civilian encounters. As stated by then-Chief Saunders, “At the end of the day, when we get this right, what we’ll be able to do is identify and monitor potential systemic racism” (Doucette 2019).

The purpose of this report is to review empirical research on anti-Black racial profiling involving the Toronto Police Service. The Toronto Police Service has been at the heart

of the Canadian racial profiling debate (Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario Criminal Justice System 1994). The report begins by reviewing various definitional issues related to the concept – including the concept of “carding” as described by Justice Michael Tulloch in his recent report (Tulloch 2019). The discussion of definitional issues is followed by a theoretical discussion of the possible causes of racially biased policing. This section will describe the various explanations that have been used to account for the existence of racial profiling in police stop and search practices including explicit (conscious) and implicit (unconscious) bias, racial stereotyping, actuarial/ statistical discrimination and institutional/ systemic practices. It will be argued that the research literature strongly suggests that racially biased policing can exist in the absence of individualized, overt racism or racial malice. One does not have to prove that individual police officers are explicitly or overtly racist to prove that racial profiling exists.

The following section of the report will explore research – conducted over the past 25 years – that has attempted to document the existence of racial profiling involving the Toronto Police Service and the extent that biased policing practices impact Toronto’s racialized communities. The report explores the various research methodologies that have been used to document racial profiling in Toronto, including qualitative interviews, general population surveys and official police-generated data (including data on carding or street checks). This section highlights research evidence that demonstrates that racial profiling has existed – and continues to exist – in Toronto and that TPS stop, question and search practices (SQS) have had a hugely disproportionate impact on Toronto’s Black community.[1]

The report then turns to a discussion of the possible benefits of police “street checks”

and police “stop, question and search” (SQS) practices. I first review police arguments that street checks, SQS practices and other forms of proactive street policing are valuable law enforcement tools that help reduce crime. This section will demonstrate that the empirical evidence supporting this thesis is highly contested. Overall, while there is research to suggest that police stop, question and search practices can identify offenders and reduce crime in some contexts, evidence also suggests that these crime reduction effects

are quite small, inconsistent, short-term and limited to specific neighbourhoods or communities. In general, the bulk of the research suggests that SQS practices are a highly inefficient police tactic.

This following section of the report reviews research that has documented the impact of racially disproportionate policing – including street checks – on racialized individuals and communities. These consequences include: 1) mental health problems; 2) lack of trust or faith in the police and broader criminal justice system; 3) racial disparities within the criminal justice system; and 4) blocked educational and employment opportunities. This section of the report will also discuss the issue of data retention. It will be maintained that the retention of carding or street check data may continue to have an adverse impact on the individuals included in police databases. Furthermore, since Black citizens are greatly over-represented within the street check data, the retention of data will likely have a disproportionate impact on members of the Black community. The report concludes that the documented consequences of these street check practices significantly outweigh the potential benefits.

The last section of the report provides a brief discussion of policy implications. It will be maintained that a variety of strategies – including improved screening of police recruits, the recruitment and retention of racialized officers, anti-bias training, improved regulations and guidelines for police stops and improved supervision and monitoring of front-line officers – are required to reduce racial disparities in police stop, question and search practices and reduce the negative impact that biased policing has on racialized communities. It will also be argued that the improved collection of race-based data is required to evaluate the impact of anti-bias initiatives. It will be argued that improved data collection and dissemination will also increase transparency, improve police accountability, and help improve public confidence in the police and broader justice system.

Definitional issues

Over the past three decades, the term racial profiling has become part of the popular lexicon. The term has appeared frequently in everything from academic manuscripts, government reports and news coverage to popular music, movies and television. The term racial profiling has also been used to describe various phenomena including the behaviour of customs and immigration officers, judges, lawyers, private security personnel, teachers, medical professionals, public servants, and members of the general public.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) defines racial profiling as: “Any act or omission related to actual or claimed reasons of safety, security or public protection by an organization or individual in a position of authority, that results in greater scrutiny, lesser scrutiny or other negative treatment based on race, colour, ethnic origin, ancestry, religion, place of origin or related stereotypes” (OHRC 2019: 15). The OHRC’s revised definition of racial profiling builds and expands on its earlier 2003 definition. The new definition can be broken down into the following core elements (OHRC 2019: 15-16):

- Act or omission: adds a reference to “omission” to encompass situations where authority figures fail to exercise due diligence based on racial stereotypes about certain categories of complainants or victims

- Actual or claimed reasons: adds reference to “claimed reasons” to acknowledge that authority figures may not always act based on objective concerns about safety, security, and public protection

- Safety, security and public protection: recognizes that racial profiling is uniquely focused on actions associated with safety, security and public protection, whether in law enforcement or other contexts including education, transportation, health care, employment and border security

- By an organization or individual: refers to both organizations and individuals to recognize that racial profiling may be systemic or individual

- In a position of authority: recognizes that racial profiling is particularly associated with the actions of authority figures

- Results in greater scrutiny, lesser scrutiny or other negative treatment: recognizes that racial profiling may manifest itself through greater scrutiny, lesser scrutiny (of victimization), or other negative treatment that is not exclusively related to scrutiny

- Based on race, colour, ethnic origin, ancestry, religion, place of origin or related stereotypes: captures action based on either race-related Code grounds or related stereotypes to recognize that findings of racial profiling can be made in the absence of overt stereotyping.

While acknowledging the utility of the broad OHRC definition, it is important to note that, in

the research literature, the term racial profiling is most often used in reference to police stop, question and search activities (see Rice and White 2010). Many scholars make a conceptual distinction between racial profiling and other forms of racially biased policing. Racially biased policing is a general term that refers to possible racial discrimination with respect to a wide variety of discretionary police behaviours that include stop and search practices, but also include arrest decisions, charging practices, decisions related to pre-trial detention, sentencing recommendations and use of force. Racial profiling, at least for the purposes of this report, focuses specifically on police surveillance and street interrogation practices.

Racial profiling can be said to exist when the members of a certain racial or ethnic group become subject to greater levels of law enforcement surveillance than others. Racial profiling, therefore, refers to racial disparities with respect to police stop and search activities (sometimes referred to street checks or carding), increased police patrols in racialized neighbourhoods and undercover activities or sting operations that selectively target particular racial or ethnic groups. Furthermore, racial profiling exists when racial differences or disparities in police surveillance activities cannot be explained by racial differences in criminal activity, traffic violations, citizen calls for service or other legally relevant factors (see Wortley and Tanner 2005; Wortley and Tanner 2003). This somewhat narrow definition is highly consistent with definitions provided by American scholars. For example, Ramirez and Hoopes define racial profiling as “the inappropriate use of race, ethnicity or national origin rather than behaviour or individualized suspicion to focus on an individual for additional investigation” (Ramirez and Hoopes 2003: 1196). Similarly, Warren and Tomanskovic-Devey (2009: 344) state that racial profiling “is a term used to describe the practice of targeting or stopping an individual based primarily on race or ethnicity, rather than on individualized suspicion or probable cause.”

As highlighted by Paulhamus and her colleagues (2010), the academic literature has also drawn a distinction between what has been called “hard racial profiling” (cases in which the police stop civilians solely because of their racial background) and “soft racial profiling” (the use of race or ethnicity as one of several factors in the decision to stop a civilian). Proponents of “soft profiling” definitions argue that racially biased policing exists if race contributes to police decisions to stop, question and search individuals. For example, data may reveal that the police are most likely to stop and search male civilians, late at night, within poor, high-crime communities. However, if Black males traversing these same communities, during the same time of day, are significantly more likely to be stopped than White males, this would constitute evidence of racial profiling.

Profiling could be said to exist because, in addition to gender, time of day and type of community, race still impacts police decision-making. By contrast, advocates of “hard profiling” definitions would likely argue that racial bias does not exist in this scenario because race was only one of several factors – including gender, community crime level and time of day – that influenced officer decisions to stop and detain individuals. They would likely argue that this data reflects a pattern of “criminal” rather than “racial” profiling (Satzewich and Shaffir 2009).

Some proponents of the “hard profiling” position have argued that racial bias cannot be said to exist if there is a legal or legitimate reason for stopping the civilians in question. I disagree with this argument. Consider, for example, the following hypothetical situation. Suppose that a police officer was assigned to patrol a particular stretch of highway. Also assume that this officer never stops drivers unless they are exceeding the speed limit. In other words, all of his stops are clearly “legitimate.” However, also assume that this officer stops eight out of every 10 racialized speeders he encounters while on patrol (80%), but only stops one out of every five White speeders (20%). In other words, this officer is four times more likely to stop racialized drivers than White drivers who are exceeding the speed limit. In my opinion, this police officer could still be guilty of racial bias, even though all his stops are legally justifiable.

A similar example might be applied to illegal drug use. Assume that an officer stops and searches every racialized civilian he witnesses smoking marijuana in public. Also assume that this same officer decides to ignore most of the White civilians he sees engaged in the same drug using activity. Although it could be argued that the officer has a legally legitimate reason for stopping and searching racialized drug users, the fact that he refrains from stopping and searching White drug users is evidence of racial profiling.

In sum, although the term racial profiling has been used in a wide variety of criminological and sociological contexts, this report focuses exclusively on possible racial biases with respect to police street checks or stop, question and search (SQS) activities. To determine whether systemic racial profiling exists or not, researchers much first establish that some racial or ethnic groups are more likely to be stopped, questioned and/or searched by the police than others. If large racial disparities do not exist, it is highly unlikely that racial profiling is a problem. The next task is to explore the possible reasons behind any observed racial differences in exposure to involuntary police contact. In other words, can racial differences in the exposure to police stop and search activities be explained by other legally relevant factors? The report returns to this question – with a focus on the Toronto Police Service – after discussing the potential causes or reasons behind racial profiling.

A note on Justice Tulloch’s definition of “carding”

Public discussions concerning racial profiling in Ontario have been complicated by a variety of competing definitions. For example, in his 2018 report, the Honourable Michael Tulloch draws a strong distinction between “street checks” and what he refers to as “carding.” Justice Tulloch defines police carding as: “Situations in which a police officer randomly asks an individual to provide identifying information when there is no objectively suspicious activity, the individual is not suspected of any offence and there is no reason to believe that the individual has any information on any offence. That information is then recorded and stored in a police intelligence database” (Tulloch 2018: xi). In a later section of the report, Justice Tulloch makes a distinction between “legitimate” street checks and carding:

Many of the issues surrounding carding and street checks stem from a misunderstanding of the terms themselves. A street check is where information is obtained by a police officer concerning an individual, outside of a police station, that is not part of an investigation. This is a very broad category of police information gathering, and much of it is legitimate intelligence gathering of potentially useful information. Carding, as referred to in this report, is a small subset of street checks in which a police officer randomly asks an individual to provide identifying information when the individual is not suspected of any crime, nor is there any reason to believe that the individual has information about any crime. This information is then entered into

a police data-base (Tulloch 2018: 4).

Justice Tulloch argues that street checks often reflect legitimate police intelligence gathering activity. By contrast, due to their randomness, carding practices are an illegitimate practice that should be eliminated.[2]

In my opinion, the definitions of both “street checks” and “carding” provided by Justice Tulloch are incomplete when it comes to studying the phenomena of racial profiling. First of all, by its very definition, racial profiling is not random or arbitrary. Racial profiling is caused by racial bias (see discussion below) and thus is strongly associated with the race of civilians – or the racial composition of neighbourhoods – subject to police activity. Furthermore, long before Ontario’s new street check regulation and Justice Tulloch’s report, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms prohibits arbitrary police detentions. Thus, Justice Tulloch’s call to eliminate “carding” is nothing new.

Another weakness with Justice Tulloch’s definition of “carding” is that it does not acknowledge the concept of the pre-text stop – an important concept within the racial profiling literature. Pre-text stops involve officers using minor offences (i.e., traffic violations, jaywalking, by-law violations, etc.) as a justification, excuse, or pretext to investigate more serious criminal activity (e.g., illegal drugs, illegal firearms, etc.). American research suggests that Black civilians are much more likely to be subject to pretext stops than people from other racial backgrounds (see Rushin and Edwards 2021; Gizzi 2011; Harris 2002; Harris 1997). Similar research and monitoring is required in Toronto and other Canadian jurisdictions (see discussion below).

A problem that could arise with the use of Justice Tulloch’s definition of “carding”

is that it seems to appear to imply that racial profiling cannot exist if officers have a “legitimate” or “legally justifiable” reason for stopping or detaining an individual.

I disagree. As discussed above, racial profiling still exists if officers pay more attention to law violations committed by Black and other racialized civilians than law violations committed by White civilians. As a result, the focus of the analysis provided in this report is on racial disparities with respect to police stop, question and search (SQS) activities. It is not limited to police activities that Justice Tulloch would explicitly identify as “carding” or “street checks.”[3]

Furthermore, a focus on police SQS activities better captures the concerns of Black and other racialized communities. For example, previous research indicates that when it comes to addressing issues related to racial profiling, the police and the community have very different conceptions of street checks. While the police view street checks as a specific intelligence tool, racialized communities view street checks more literally – as being stopped, questioned or “checked” by the police on the street (see Wortley 219).

The causes of racial profiling

What might be the possible cause or source of racial profiling or racially biased policing? Although researchers have spent a great deal of time and effort trying to both define and measure this phenomena, less attention has been given to developing an integrated theory that would help explain the existence of racial profiling by the police. Consistent with the work of Tomaskovic-Devey, Mason and Zinraff (2004), I propose five different theoretical models that might help explain racial profiling: 1) the racial animus model; 2) the statistical discrimination/criminal stereotype model; 3) the implicit bias model; 4) the institutional model; and 5) the police deployment model. It should be stressed that the first three models focus

on the intent and activities of individual police officers, while the final two models focus on organizational mechanisms. It is important to note that the two organizational models do not require any racial bias in officer or organizational intent, although they will produce racially biased police practices and disproportionately impact the members of racialized communities (see Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2004: 3).

The racial animus model

The racial animus model holds that, within any given society, some people have a conscious dislike or prejudice against the members of other racial groups. To the extent that police services reflect the population that they serve, it is likely that some police officers will also have overtly racist beliefs that may promote or condone the poor treatment of racialized groups. Fortunately, North American research suggests that openly racist beliefs or prejudice have declined significantly over the past 50 years (see Schuman et al 1997; Henry and Tator 2005).[4] Thus, it is likely that overt or explicit racial animus will be limited to a relatively small number

of police officers. Nonetheless, these few racist officers could significantly increase the rate of stop and search for targeted racialized groups and subsequently damage police-community relationships (Tomoskovic-Devey et al. 2004: 9).

According to the racial animus model, if police services can only identify and terminate these few “bad apples,” the problem of racial profiling will be eliminated. However, since most modern police services formally proscribe against racist attitudes and behaviour, the identification of overt racism among police officers is not a simple task. Indeed, the actual expression of racist beliefs by police officers, especially as they pertain to the treatment of racialized civilians, is likely to be rarer than the incidence of racial prejudice among police officers (see Tomoskovic-Devey et al. 2009: 9).

It is possible for some police services to have more “bad apples” than others. This might occur if police recruitment procedures do not effectively screen for racial animus or if informal field training processes encourage the expression of racist beliefs. Racial animus is also more likely to flourish within police organizations in which prohibitions against racist behaviour are not properly enforced (see Tomoskovic-Devey et al. 2009).

It should be stressed that the racial animus or “bad apples” explanation for racial profiling is somewhat popular among certain police administrators because it holds that racial profiling is an isolated problem, rather than a systemic issue, involving only a few corrupt police officers (see Tator and Henry 2006). On the other hand, many police officers and police union leaders have come to equate the term “racial profiling” with accusations of overt racism. As a result, when their police service is faced with allegations of racial profiling, many officers believe that they as individuals are being accused of holding overtly racist beliefs and are deliberately trying to harm racialized communities. Not surprisingly, many police officers find such accusations offensive (see Paulhamus et al. 2010; Satzewich and Shaffir 2009; Ioimo et al. 2007).[5]

In sum, although it cannot be totally dismissed, the racial animus model only provides a theoretically limited explanation for racial profiling. Other explanations hold that racial profiling is not rooted in the overt racism of individual police officers. Rather, profiling practices stem from the broader police culture and specific organizational practices.

The statistical discrimination/criminal stereotype model

Racial profiling may also be caused by racial stereotyping with respect to criminal behaviour. In other words, individual police officers may develop beliefs, stereotypes

or profiles about the types of people who are more or less involved in criminal activity. These stereotypes might emerge as a result of socialization into the police subculture, personal job experiences, access to crime statistics or exposure to media depictions and mainstream stereotypes concerning crime and violence. For example, police supervisors and front-line officers may be exposed to crime statistics that show that

a large proportion of gun-related murders and gun possession charges involve Black male offenders. This pattern may be reinforced by racialized media coverage of crime and their own experiences on patrol. Exposure to this information may cause them to believe that it is more rational for police officers to pay special attention – or otherwise suspect – Black males than other civilians. Such conscious stereotyping could directly contribute to racial profiling. Far from an “individual problem,” racial stereotyping can become an informal, institutional phenomenon.

The mental construction of the “typical offender” has sometimes been referred to as “criminal profiling” and often involves race or ethnicity as well as other personal characteristics including age, gender, social class and personal appearance (see Satzewich and Shaffir 2009). Stereotyping may play an important role with respect to proactive policing.[6] Police supervisors, as well as the general public, put pressure on police officers to identify criminal offenders

and subsequently ensure public safety. Demonstrating a proficiency at identifying and apprehending criminals may also be directly related to future promotion and career opportunities. Thus, many officers may feel a need or pressure to categorize people they encounter on the street by their likelihood of being involved in criminal activity. As a result, officers may feel that it would be more efficient or rational, from a crime-fighting perspective, to focus their surveillance activities on young, racialized males than, for example, older White females.

In a classic observational analysis of police patrol practices, Skolnick (1966) observed that the police in the United States tend to perceive young Black males as "symbolic assailants" and thus stop and question them on the street as a means of effective or efficient “crime prevention.” Anderson (1990) further articulates this tendency in his ethnographic study of a multi-racial community located in a large American city. In documenting the general police tendency to stop, search and harass young Black citizens as part of their routine patrolling activity, Anderson notes that:

On the streets, colour-coding works to confuse race, age, class, gender, incivility, and criminality, and it expresses itself most concretely in the person of the anonymous Black male. In doing their job, the police often become willing parties to this colour-coding of the public environment... a young Black male is a suspect until he proves he is not (Anderson 1990, pp. 190-191).

While patrolling the streets, the police may engage in the same type of actuarial risk assessment – and subsequent statistical discrimination – used by insurance companies (see Feeley and Simon 1992). For example, it is well known that insurance companies charge much higher premiums for young male drivers than drivers with other demographic characteristics. The justification for these higher rates is that, from a statistical standpoint, younger males are more likely to engage in risky driving behaviours (speeding, driving under the influence, etc.) and are more likely to become involved in serious traffic accidents. The same logic of statistical probability may be employed by the police on the street. According to individual and collective police experiences, young racialized males may be identified as the most likely to be involved in serious crime and violence. Thus, just as all young males must suffer from higher insurance premiums, all young racialized males, regardless of their individual behaviour, pay a higher cost when it comes to police attention.

Even though the majority of young males may have a clean driving record, they must pay higher insurance premiums because of the actions of a relatively few members of their demographic group. Similarly, even though the majority of young racialized males are law-abiding, they must pay a higher criminal justice premium: a criminal justice premium that manifests itself with respect to much greater exposure to police stop, question and search activities. Frank Zimring, an American academic who has championed the use of stop and search tactics, admits that, due to statistical discrimination, Black and other racialized males are going to be disproportionately subjected to police stops. He further concedes that this amounts to “a special tax on minority males” (Bergner 2014). This theme is further elaborated by Tomaskovic-Devey and his colleagues (2004: 12) when they state that:

The use of profiles in law enforcement is thought to increase the efficiency of officers, and, consequently, the police organization as a whole. Unfortunately, criminal profiles are often based on stereotypes of characteristics related to different groups. In turn, group membership becomes a proxy for suspected criminality. An obvious result of such group generalizations in policing is that a widely cast net subjects many noncriminal minorities to police scrutiny while White people – both criminal and noncriminal – escape such surveillance. Criminal status no longer represents an individual characteristic but is shaped by group racial status.

It is important to note that this process of racial stereotyping does not necessarily involve racial animus or malice. Instead, police officer stereotypes about the “probable criminal” may be rooted in a professional desire to be efficient or effective when using limited law enforcement resources. Nonetheless, such racial stereotyping, even when grounded in statistics and conducted in the name of public safety, can have a profoundly negative impact on racialized communities (see discussion below).

The implicit bias model

The discussion, immediately above, referred to processes of explicit criminal profiling or criminal stereotyping that may consciously impact the actions of individual police officers. However, others have argued that implicit cognitive biases can also exist at the subconscious level (see Fridell 2017, White and Fradella 2016; Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2004 for detailed discussions about the psychology behind the development of implicit cognitive biases). The basic argument is that people, in order to deal with an excess of information, learn to categorize. Categorization provides cognitive efficiency because it enables people to organize information and make decisions more quickly.

Research suggests that people tend to categorize themselves and others into groups automatically and unconsciously. Lacking detailed information about specific individuals, people categorize others on the basis of highly visible and easily attributable characteristics such as race, gender and age. In turn, this process of categorization has an almost automatic impact on how we perceive strangers and often directly impacts how be behave towards them. There is also a general tendency to make in-group and out-group distinctions and for people to display in-group favouritism. Out group biases, including negative attributions, may have a subconscious impact on police decision-making. As Tomaskovic-Devey and his colleagues (2004: 15-17) state:

This general tendency to make in-group and out-group distinctions has implications for racial bias in police stops. Because there is a tendency toward automatic display of in-group favouritism on making in-group and out group distinctions, officers may process information about driver threat in the context of both the driver’s and officer’s racial background. When engaging in proactive policing such as patrolling

a neighbourhood or interstate, officers are attempting to process large amounts of information in short time periods, with little individual information. They observe many people doing many things in dynamic settings. Acting as “cognitive misers,” they attempt to process the information in a way that allows them to be efficient in evaluating all that is observed. Placing information in categories is a primary way that this is accomplished. These categories trigger stereotypes that help determine what seems suspicious or out of place. The types of information police routinely focus on are those that tend to be associated with criminality and public safety. Police can be expected to focus in particular on behaviour, language, vehicle qualities, and appearances (i.e., clothing, jewelry) and settings that invoke images of criminality or threats to public safety. When the officer is making discretionary choices about who to pull over and who to cite, this type of cognitive bias may make cars driven by minority drivers seem slightly more dangerous.

The idea that unconscious or implicit racial bias can impact police decision-making has seemingly been embraced by a number of Canadian law enforcement agencies – including the Durham Regional Police Service, the Peel Regional Police Service, the Ottawa Police Service and the Toronto Police Service. These services have all commissioned the delivery of a training program known as “Fair and Impartial Policing” (fipolicing.com). This program, developed by criminologist Lorie Fridell, is designed to increase police officer awareness of their own implicit or unconscious biases and how these biases may impact how they treat or

respond to people from diverse backgrounds. Unfortunately, at the time of writing this report, the research team could not identify a single published article that evaluated implicit bias training in the Canadian context. Thus, it is impossible to determine whether implicit bias training has actually reduced racially biased policing practices among Canadian police services.

Overall, the research literature suggests that both conscious and unconscious stereotyping, at the level of the individual police officer, might contribute to racial differences in police stop and search activities. However, to truly comprehend the phenomenon of racial profiling, organizational as well as individual factors must be considered.

The institutional model

In the sections above, the report discussed how racial profiling may be the result of conscious racial stereotyping – often justified as criminal profiling – or implicit biases that are outside the consciousness of individual police officers. While conscious stereotypes or criminal “profiles” may be widely held within the police subculture and could be transmitted through informal socialization processes within police organizations, implicit biases, on the other hand, result from normal cognitive functioning and are thus common among people from all occupations and social backgrounds. However, we also cannot dismiss the possibility that certain police services actually develop profiling practices that are formally sanctioned by the organization’s leadership. In the United States, the use of formal racial profiles dates back to the late 1970s, when the federal government created drug courier profiles for the purpose of apprehending drug traffickers at American airports. The practice was later extended to highways and became a widespread policy in the early 1990s after the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) offered drug interdiction training to local and state patrol officers.

During this time, race was introduced as both a legitimate and normal characteristic of drug courier profiles, and police departments used these profiles to make stop and search decisions. A highway drug interdiction program, known as Operation Pipeline, trained more than 27,000 officers from 48 states how to use these profiles (Harris 2002; Warren and Tomaskovic-Devey 2009). There is also evidence to suggest that some Canadian police services may have received training from the DEA that is consistent with the principles of Operation Pipeline (see discussion in Tanovich 2006). There is also emerging evidence to suggest that formal, race-based criminal profiles have been extended to assist police in the identification of street gang members as well as drug traffickers (see Zatz and Krecker 2003; Barrows and Huff 2009).

In sum, it is important to note that the source of racial profiling behaviours cannot always be traced to the racialized beliefs, stereotypes or unconscious biases of individual police officers. Nor can it always be linked to racial stereotypes that are promoted within the informal police subculture. Sometimes the source of racially biased stop and search activities lies in the formal policies and training procedures of police organizations themselves. In other words, even officers who do not hold racist beliefs may engage

in racial profiling when they follow the formally sanctioned orders or instructions provided

by their supervisors and trainers. Once again, although the establishment of formal, race-based criminal profiles are often justified on the basis of effective policing and public safety, they also serve to stigmatize entire racialized communities and subject all members of identified groups to differential police treatment.

The police deployment model

Research suggests that police officers are not often deployed evenly across all areas of a community or urban area. For example, neighbourhoods with high rates of violent crime (homicides, shootings, assaults, robberies, gang activity, etc.) will typically receive more police patrols than neighbourhoods with low levels of violent offending. Indeed, modern, data-driven police management practices entail that crime “hot spots,” areas with higher than average rates of violent crime, should receive a disproportionate share of police attention. In addition to the uneven deployment of police patrols across neighbourhoods, research also suggests that the style of policing may vary across communities. Several studies have documented, for example, that policing is often more proactive or aggressive in areas with high crime rates. By contrast,policing tends to be more reactive and less aggressive in areas with low crime rates (Tomankovic-Devey et al. 2004; Nobles 2010; Parker et al. 2010).

Research also demonstrates that recent immigrants and certain racialized groups are over-represented in economically disadvantaged, high-crime communities, while White people are over-represented in wealthy, low-crime communities. Thus, by default, racial minorities are more likely to be subjected to more policing – including aggressive stop and search activities – as a function of the where they reside.[7] Critics have argued that the greater police presence in racialized communities, combined with a more aggressive or proactive policing style, represents a form of systemic bias that will ultimately expose racialized civilians to negative police encounters. In other words, according to the police

deployment model, racial profiling is not necessarily the product of racial stereotyping or racial animus. It might, in fact, be partially explained by where the police are deployed and how the police exercise their authority across different communities.[8]

One further note of caution when discussing the alleged “objectivity” of police deployment practices that are based on the statistical analysis of neighbourhood crime data. As discussed later in this report, biased police practices can produce biased police data. For example, biased policing may be at least partially responsible for the high rates of crime associated with curtained neighbourhoods or communities. Biased data, in turn, can be used to justify the biased police practices. The relationship between crime rates and aggressive, proactive police practices may be a form of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Summary

The purpose of this section has been to review possible explanations for racial profiling. Future research is needed to determine which of the above explanations are the most valid, or whether all five theoretical frameworks occur simultaneously and thus account for some proportion of the racial profiling phenomena. Some scholars believe that, since racial animus has declined significantly within society, overt racism will only explain a small amount of racial profiling behaviour. Similarly, due to political pressures, it is likely that organizational guidelines that directly target certain racial groups are becoming increasingly rare. However, racial stereotyping, cognitive biases and systemically biased police deployment practices likely remain prevalent and thus are still highly relevant to both researchers and policy-makers. It

is also important to note that some of the theoretical models discussed above are more amenable to policy than others. Formal race-based criminal profiles can be eliminated. Police services can screen for racial animus in new recruits, and discipline or terminate sworn officers who display overtly racist attitudes or behaviours. Policing in high-crime neighbourhoods can also be restricted to rapid response to calls for service, rather than proactive policing practices that often subject law-abiding residents to aggressive street interrogations. However, as noted by Tomaskovic-Devey, Mason and Zingraff (2004: 25), implicit biases and individual-level stereotyping may be more difficult to identify and control.

Evidence of racial profiling by the Toronto Police Service

A review of the international literature reveals that five different methodological strategies have been employed by researchers to explore racial disparities in police stop, question and search activities. These five research methodologies include: 1) qualitative methods; 2) survey methods; 3) observational methods; 4) official statistics on police stops; and 5) official data on street checks or carding. In this section of the report, we examine previous research that has attempted to explore the issue of racial profiling in Toronto. A review of the literature reveals that, with respect to the Toronto Police Service, racial profiling has been examined using only three of the five research methodologies described above: qualitative methods, survey research and official statistics on street checks (also referred to as contact cards, field information reports and regulated interactions). We could not identify an observational study of racial profiling conducted in the Toronto region. Furthermore, despite public demand and report recommendations, the TPS has never conducted a study to examine racial disparities with respect to traffic and/or pedestrian stops.[9]

The review of research evidence begins with an examination of qualitative studies before turning to a discussion of survey research conducted prior to the 2017 implementation of Ontario’s new street check regulation. After examining official TPS street check data and describing the dramatic decline in documented street checks post-regulation, the report reviews new survey research conducted since 2017. Results from these recent surveys challenge the argument that Ontario’s Street Check Regulation has reduced racial profiling and underscore the great need for race-based data collection on TPS stop, question and search activities.

Qualitative research

Much of the early work on racial profiling in the United States and Great Britain consisted of one-on-one interviews or focus groups with racialized youth (Jones-Brown 2000; Brunson 2007). In the Canadian context, James (1998) conducted intensive interviews with over 50 Black youth from six different cities in Ontario – including Toronto. Many of these youths reported that being stopped by the police was a common occurrence for them. There was also an almost universal belief that skin colour, not style of dress, was the primary determinant of attracting police attention. As one of Black male respondent noted: "They drive by. They don't glimpse your clothes, they glimpse your colour. That's the first thing they look at. If they judge the clothes so much why don't they go and stop those White boys that are wearing the same things like us. I think that if you are Black and wearing a suit, they would think that you did something illegal to get the suit" (James 1998: 166).

James concludes that the adversarial nature of these police stops contributes strongly to Black youths’ hostility and negative attitudes towards the police (James 1998: 173). Neugebauer's (2000) informal interviews with 63 Black and White Toronto youth produced very similar results. Although the author found that teenagers from all racial backgrounds often complain about being hassled by the police, both White and Black youth agree that Black males are much more likely to be stopped, questioned and searched by the police in Toronto than teens from other racial backgrounds.

During a series of public consultations in Toronto, conducted by the Ontario Government’s Review of the Roots of Youth Violence, strikingly similar stories were communicated to the lead investigators. Black and Indigenous youth from Toronto repeatedly told the inquiry that they felt targeted by the police – often through aggressive police stop and search activities – and that this targeting had eroded their trust in the police and the broader criminal justice system (McMurtry and Curling 2008a; McMurtry and Curling 2008b).

In another qualitative study, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) gathered detailed testimonials from a non-random sample of over 800 people in Ontario – most of them Black residents of Toronto – who felt that they had been the victim of racial profiling (Ontario Human Rights Commission 2003). The OHRC project was not only successful in providing vivid descriptions of specific racial profiling incidents, but also provided detailed information concerning how these incidents negatively impact both racialized individuals and communities (Williams 2006). The OHRC conducted a second major investigation into racial profiling in 2015. This investigation involved consultations with a non-random sample of over 1,600 individuals and organizations. Once again, the Commission heard that racial profiling is a major problem in Toronto (Ontario Human Rights Commission 2017).

Importantly, after the release of the first two OHRC investigations, the existence of systemic racism within policing has been acknowledged by representatives from both the TPS and TPSB (see Ontario Human Rights Commission 2017; Aguilar 2020; Fox 2020; Goodfield 2020; Toronto Police Services Board 2020; CBC News 2018; Doolittle 2009).

Finally, since 2018, as part of its current inquiry into racially biased policing, the OHRC has conducted a series of interviews and focus groups with members of Toronto’s Black communities and members of the TPS. As with its earlier investigations, the OHRC continued to hear complaints about racial profiling and unfair TPS stop and search

practices. Civilian allegations have also been supported by the testimonials of police officers. In sum, the overall narrative that emerges from two decades of qualitative OHRC research is that racial profiling – within the TPS – is still a problem.

The argument that little has changed with respect to racial profiling in Toronto is reinforced by a number of recent, smaller-scale qualitative studies. These studies, all conducted since 2017 and the imposition of Ontario’s Street Check Regulation, focus on Black youth from disadvantaged Toronto communities. All of these studies document negative encounters between Black youth and the TPS, including allegations of racially biased stop and search practices. All document how TPS stop and search activities contribute to community distrust of the police, reduce the likelihood that youth will report crime, and increase reliance on self-help strategies designed to ensure personal safety (see Haag 2021; Samuels-Wortley 2021; Samuels-Wortley 2020; Nichols 2018).

Findings from the above government inquiries and academic studies were reinforced

by the Community Assessment of Police Practices (CAPP) research project. During the summer of 2014, the research team, funded by the Toronto Police Services Board, conducted an ambitious community survey that involved interviews with a non-random sample of 404 residents of 31 Division – an area encompassing one of the most racially diverse and socio-economically disadvantaged regions of Toronto. Approximately half the sample self-identified as Black, 12.1% as White and 30.4% as members of another racialized group. The results of the study indicate that respondents had little trust or confidence in the police. Furthermore, regardless of their own racial background, the majority of respondents felt that the Toronto police engaged in racial profiling. Consistent with this belief, Black respondents were much more likely to report that they had been recently stopped, searched and “carded” by the police than youth from other racial backgrounds. Compared to their White counterparts, Black youth were also more likely to report that, during police encounters, they had been intimidated and treated with hostility and disrespect (see Price 2014).

As discussed briefly above, qualitative methodologies have also been used to study police officer perceptions of the racial profiling issue. For example, following a series of newspaper stories on racially biased policing, former Toronto Police Chief Julian Fantino asked several senior Black officers, including Superintendent Keith Forde, to investigate how allegations

of racial profiling were being perceived by Black members of the force. In response to this request, 36 Black officers from the TPS met to discuss the issue of racial profiling in October 2003. A focus group format was utilized. All of the participating TPS officers agreed that racial profiling was a problem and that the criminal stereotyping of Black citizens was widespread within the Toronto Police Service. The majority of respondents also reported that they themselves had been the victim of racial profiling. Three officers, in fact, reported that they had been stopped and questioned by the police on more than one occasion in the same week, and six officers reported that they had been stopped on more than 12 occasions in the same year. In a subsequent presentation of these findings to their fellow officers, the senior Black officers tasked with the investigation began with the statement: “We know that racial profiling exists” (see Tanovich 2006: 35-36).

Similar research on the perceptions and experiences of Black police officers has recently been conducted by Dr. Akwasi Owusu-Bempah (Department of Sociology, University of Toronto). Owusu-Bempah (2015) conducted in-depth interviews with a non-random sample of 50 Black male police officers – many employed by the TPS. He argues that this police sample can provide unique insights into the reality of racism within law enforcement because of the respondents’ dual identities and experiences as both Black males within Canadian society and their experiences as police officers.

Almost all the Black male police officers involved in this study reported that they had observed racial profiling and other forms of racially biased policing on the job. Most admitted that they had worked with fellow officers who openly engaged in racial profiling and condoned the practice. Indeed, the majority indicated that they themselves had been subjected to racial profiling on multiple occasions – even after becoming a police officer.

All agreed that such racial bias has had a negative impact on Toronto’s Black community, and has produced distrust between the police and Toronto’s Black residents. Many of the officers argued that racially biased policing is caused by racial stereotypes that associate the Black population with both criminality and dangerousness (Owusu-Bempah 2015).

Summary

In conclusion, qualitative research, involving both Toronto residents and Toronto police officers, has produced findings that are highly consistent with the argument that the Toronto police engage in racial profiling. The nature of these qualitative results has not changed over the past three decades. Proponents argue that qualitative research methods can help researchers make sense of police stop and search statistics and further understand how police surveillance activities impact the lives of racialized people. As Brunson (2010: 221) notes, although statistics may help us identify racial differences in overall exposure to police surveillance activities, “they have not elicited the kind of information that would allow researchers to acquire deeper understandings of meanings for study participants.

On the other hand, qualitative research methods provide a unique opportunity to examine

and better understand the range of experiences that may influence individuals’ attitudes towards the police.” Stewart (2007: 124) adds: “A qualitative research approach allows researchers to measure the various sources of negative direct and vicarious police experiences and understand the meaning one attaches to these experiences.”

Although qualitative studies tend to provide great detail about police encounters and the "lived experience" of racial minorities, they have often been criticized for being based on small, non-random samples – usually from economically disadvantaged communities. In other words, it is often difficult to generalize the results of qualitative research to the wider population. Furthermore, most qualitative studies focus on the experiences of racialized people in isolation. In other words, they do not directly compare the experiences of racial minorities with the experiences of White people. These facts alone have led to charges that the qualitative research evidence documenting racial profiling is "selective" or "anecdotal" and thus not truly representative of police behaviour (see Wilbanks 1987; Melchers 2006). It should be stressed, however, that police denials of racial profiling are equally “anecdotal” and have thus been largely dismissed by racial minority organizations and anti-racism scholars (see Tator and Henry 2006). In sum, although qualitative research methods have considerable value when it comes to documenting and understanding police-race relations, there is a general consensus among researchers that, when possible, they should be supplemented with more quantitative approaches.

Survey research

Unlike qualitative research strategies, survey methods often explore the opinions and experiences of citizens using large, random samples. Thus, unlike qualitative results, survey findings can be more easily generalized to the entire population in question. With respect to racially biased policing, survey methods have been used to document that racial profiling is viewed as a serious problem by a large proportion of the Canadian population. In a 2007 survey of Toronto residents, for example, respondents were asked the following question: Racial profiling is said to exist when people are stopped, questioned or searched by the police because of their racial characteristics, not because of their individual behaviour or their actions. In your opinion, is racial profiling a problem in Canada or not? The results suggest that Black Canadians are much more likely to perceive racial profiling as a major social problem than their Chinese and White counterparts. Indeed, six out of 10 Black respondents (57%) view racial profiling in Canada as a “big problem,” compared to only 21% of White and 14% of Chinese respondents.[10]

Respondents were then asked: Suppose that, in a particular neighbourhood, most of the people arrested for drug trafficking, gun violence and gang activity belong to a particular racial group. In order to fight crime in this area, do you think it would be okay or legitimate for the police to randomly stop and search people who belong to this racial group more than they stop and search people from other racial groups? According to the responses to this question, four out of 10 White respondents (39%) and a third of Chinese respondents (34%) feel that racial profiling is a legitimate crime-fighting strategy, compared to only 23% of their Black counterparts. These racial differences in opinion are statistically significant (see Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011b; Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2009).

It is important to note that, in addition to measuring public opinion about racial profiling, survey methods can also be used to measure actual experiences with police stop and search activities in Toronto. The ability for surveys to measure race – as well as other variables that may theoretically predict contact with the police – is an important methodological advance that partially addresses the crucial issue of “benchmarking”

(see detailed discussion in Wortley 2019a; Wortley 2019b). In other words, survey methods enable us to estimate whether race has an impact on police stops and searches after statistically controlling for other relevant factors.

To date, there have been six large Canadian surveys that have addressed the racial profiling issue. Five of these studies were conducted in the Toronto region and the sixth involved a national sample that included a large number of Black Toronto residents. All six studies attempted to document whether racial minorities are more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police than White people – after statistically controlling for other factors that might increase or decrease the likelihood of drawing police attention (see reviews in Wortley 2016; Owusu-Bempah and Wortley 2014).

To begin with, a 1994 survey of over 1,200 Black, Chinese and White Toronto residents (at least 400 respondents from each racial group), conducted by York University’s Institute for Social Research, found that Black people, particularly Black males, are much more likely to report involuntary police contact than either White or Asian people. For example, almost half (44%) of the Black males in the sample reported that they had been stopped and questioned by the police at least once in the past two years. In fact, one-third (30%) of Black males reported that they had been stopped on two or more occasions. By contrast, only 12% of White males and 7% of Asian males reported multiple police stops.

Multivariate analyses of these data reveal that racial differences in police contact cannot

be explained by racial differences in social class, education or other demographic variables. In fact, two factors that seem to protect White males from police contact – age and social class – do not protect Black males. White people with high incomes and education, for example, are much less likely to be stopped by the police than White people who score low on social class measures. By contrast, Black people with high incomes and education are actually more likely to be stopped than Black people with a lower-class background. Black professionals, in fact, often attributed the attention they receive from the police to their relative affluence. As one Black respondent stated: “If you are Black and you drive something good, the police will pull you over and ask about drugs” (see Wortley and Tanner 2003; Wortley and Kellough 2004).

A second study, conducted in 2000, surveyed approximately 3,400 Toronto high

school students about their recent experiences with the police (Wortley and Tanner 2005; Hayle, Wortley and Tanner 2016). The results of this study further suggest that Black youth are much more likely than people from other racial backgrounds to be subjected to street interrogations. For example, over 50% of the Black students report that they have been stopped and questioned by the police on two or more occasions in the past two years, compared to only 23% of White students, 11% of Asians and 8% of South Asians. Similarly, over 40% of Black students claim that they have been physically searched by the police in the past two years, compared to only 17% of their White and 11% of their Asian counterparts.

However, the data also reveals that students who engage in various forms of crime and deviance are much more likely to receive police attention than students who do not break the law. For example, 81% of the drug dealers in this sample (defined as people who sold drugs on 10 or more occasions in the past year) report that they have been searched by the police, compared to only 16% of students who did not sell drugs. This finding is consistent with the argument that the police focus more on civilians who engage in illegal activity than civilians who do not engage in crime.

The data further reveal that students who spend most of their leisure time in public spaces (e.g., malls, public parks, nightclubs, etc.) are much more likely to be stopped by the police than students who spend their time in private spaces or in the company of their parents. This leads to the million-dollar question: Do Black students in this study receive more police attention because they are more involved in crime and more likely to be involved in leisure activities which take place in public spaces?

While the survey data reveal that White students report much higher rates of both alcohol consumption and illicit drug use, Black students report higher rates of minor property crime, violence and gang membership. Furthermore, both Black and White students report higher rates of participation in public leisure activities than students from all other racial backgrounds. These racial differences, however, do not come close to explaining why Black youth are much more vulnerable to police contact.

Multivariate analysis reveals that after statistically controlling for criminal activity, drug use, gang membership and leisure activities, the relationship between race and TPS stop and search activity becomes even stronger. Why? Further analysis reveals that racial differences in TPS stop and search practices are, in fact, greatest among students with low levels of criminal behaviour. For example, 34% of the Black students who have not engaged in any type of criminal activity still report that they have been stopped by the police on two or more occasions in the past two years, compared to only 4% of White students in the same behavioural category. Similarly, 23% of Black students with no deviant behaviour report that they have been searched by the police, compared to only 5% of White students who report no deviance (Wortley and Tanner 2005). Thus, while the first survey, discussed above, reveals that age and social class do not protect Black people from police stops and searches, this study suggests that good behaviour also does not shelter Black civilians from unwanted police attention.

This high school survey was also able to demonstrate that, because they are subject to higher levels of police surveillance, Black youth in Toronto are also more likely to be caught when they break the law than White youth who engage in exactly the same forms of criminal activity. Consider the example of student drug dealers. As discussed earlier, we defined a drug dealer as any respondent who had sold illegal drugs on at least 10 occasions in the past year. Our findings further reveal that 65% of Black drug dealers have been arrested at some time in their life, compared to only 35% of the White drug dealers – a finding that likely reflects the fact that Black students are much more likely to be stopped and searched by the police (Wortley and Tanner 2005; Hayle, Wortley and Tanner 2016).[11]

These findings have also been replicated using a national sample of Canadian youth (12–17 years old). Fitzgerald and Carrington used data from the 2000–2001 National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (sample size=4,164 respondents) to explore whether “high-risk” visible minority youth (Black, Indigenous and Arab respondents) were more likely than White youth or “low-risk” minority youth (South Asians and Asians) to be stopped and questioned by the police. It is important to note that a high proportion of the Black respondents to this national survey were from Toronto.

Consistent with the Toronto high school survey discussed above, Fitzgerald and Carrington (2011) found that Black, Indigenous and Arab youth from Toronto and other regions of Canada were significantly more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police over the past year than White, Asian or South Asian youth. Furthermore, multivariate analyses reveal that the impact of race on police stops remains statistically significant after controlling for other theoretically relevant variables including socio-economic status, family background, parental supervision, leisure activities, neighbourhood safety and individual involvement in both violent and nonviolent crime. In other words, although high-risk racialized youth reported higher levels of criminal involvement than White youth, this did not explain why racialized youth were more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police.

Indeed, consistent with Wortley and Tanner’s (2005) findings, the results of Fitzgerald’s and Carrington’s (2011) work suggests that racial differences in police contact are greatest among youth with low levels of criminal involvement. Once again, Canadian findings suggest that “good behaviour” does not protect Black people and other minorities from unwanted police contact to the same extent that it protects White people. The authors conclude that their findings are consistent with allegations of racial profiling.

A fourth Canadian survey, conducted in 2007, involves interviews with a random sample of 1,500 White, Black and Chinese Torontonians, 18 years of age or older. Over 500 respondents were selected from each of the targeted racial groups (Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011b). Respondents were asked how many times they had been stopped and questioned by the police – while driving in a car or walking or standing in a public space – in the past two years. The results suggest that a third of the Black respondents (34%) have been stopped by the police in the past two years, compared to 28% of White respondents and 22% of Chinese respondents.

Racial differences exist for both traffic and pedestrian stops. Black people are especially likely to experience multiple police stops. Indeed, 14% of Black respondents indicate that they have been stopped by the police on three or more occasions in the past two years, compared to only 5% of White and 3% of Chinese respondents. On average, Black respondents experienced 1.6 stops in the past two years, compared to 0.5 stops for White people and 0.3 stops for Chinese respondents.

Multivariate analysis of the 2007 survey data reveals that Black males from Toronto are particularly vulnerable to police stops. One in four Black male respondents (23%) indicate that they were stopped by the police on three or more occasions in the past two years, compared to only 8% of White males and 6% of Chinese males. On average, Black males experienced 3.4 police stops in the past two years, compared to 0.7 stops for White males and 0.5 stops for Chinese males. Although Black females are less likely to be stopped and questioned by the police than Black males, they are significantly more likely to report police stops than White or Chinese females. In fact, Black females (9%) are more likely to report three or more police stops than White (8%) or Chinese males (6%). On average, Black females report 0.7 police stops in the past two years, compared to 0.4 stops for White females and 0.2 stops for Chinese females (Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011).

Survey respondents were also asked if they had been physically searched by the police in the past two years. Once again, the data reveal that Black people – particularly Black males – are more vulnerable to police searches than respondents from other racial backgrounds. Overall, 12% of Black male respondents report being searched by the police in the past two years, compared to only 3% of White and Chinese males. Black females are also more likely to report being searched by the police (3%) than White or Chinese females (1%).

The data from this survey of Toronto residents clearly indicate that Black respondents are more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than White or Chinese respondents. However, as discussed above, there are factors, besides race, that may explain Black over-representation in police encounters. For example, Black Torontonians tend to be younger and less affluent than their White and Chinese counterparts. Thus, it may be youthfulness or poverty – not racial bias – that explains why Black people are more likely to be stopped and searched. Similarly, Black people may be more likely to be stopped because they are more likely to reside in high-crime neighbourhoods, often marked by aggressive police patrol strategies. Furthermore, racial differences in behaviour, not race itself, might explain why Black people receive greater police attention. For example, compared to people from other racial backgrounds, Black people may be more vulnerable to police stops because they spend more time driving or hanging out in public spaces. Finally, Black people may be more likely to draw the legitimate attention of the police because they are more likely to be involved in traffic violations or various forms of criminal activity.

In order to address these competing hypotheses, the authors produced a series of logistic regressions predicting police stop and search experiences. In addition to race, these regressions statistically control for a variety of demographic variables including age, gender, education, household income and place of birth. Our analysis also controlled for level of crime within the respondents’ neighbourhood, frequency of driving, level of involvement in public leisure activities, alcohol use, marijuana use and criminal history.

The results of the multivariate analyses indicate that, among Toronto residents, Black racial background remains a strong predictor of police stop and search activities after statistically controlling for other theoretically relevant variables. Chinese racial background, on the other hand, is unrelated to the probability of being stopped and searched by the police. The results further suggest that the more stringent the measure of police stops, the stronger the relationship with Black racial background. For example, an examination of the odds ratios indicates that Black people are 1.9 times more likely than White people to experience one or more stops in the past two years, 2.3 times more likely to experience two or more stops and 3.4 times more likely to experience three or more stops. Furthermore, the results suggest that Black people are also 3.3 times more likely than White people to have been searched by the TPS in the past two years (Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011b).

All respondents who reported that they had been stopped and questioned by the TPS in the past two years (N=423) were subsequently asked a series of questions about their

most recent police encounter. The results clearly indicate that Black Toronto residents tend to interpret police stops more negatively than their Chinese and White counterparts. To begin with, respondents were asked if they thought their latest police stop was fair or unfair. Almost half of the Black respondents (47%) felt that their last police stop was unfair, compared to only 17% percent of Chinese and 12% of White respondents. Compared to White and Chinese respondents, Black respondents were also less likely to report that the police adequately explained the reason for the stop and were more likely to report that the police treated them in a disrespectful manner.

Respondents to this survey were also asked the following open-ended question: The last time you were stopped by the police, why do you think they stopped you? One out of every four Black respondents (25%) specifically claimed that they were stopped because of their race. By contrast, only two Chinese respondents and two White respondents cited race as the reason that they were stopped. Interestingly, both of these White respondents claimed that they were stopped by the police because they were riding in a car with Black people. With these results in mind, it is not surprising to note that Black respondents were much more likely than Chinese or White respondents to report that they were “very upset” by their last police encounter (Wortley 2011b). These results are remarkably consistent with American research that also suggests that Black people are more likely to feel that they have been treated unfairly or with disrespect during police stops (see Warren 2011).[12]

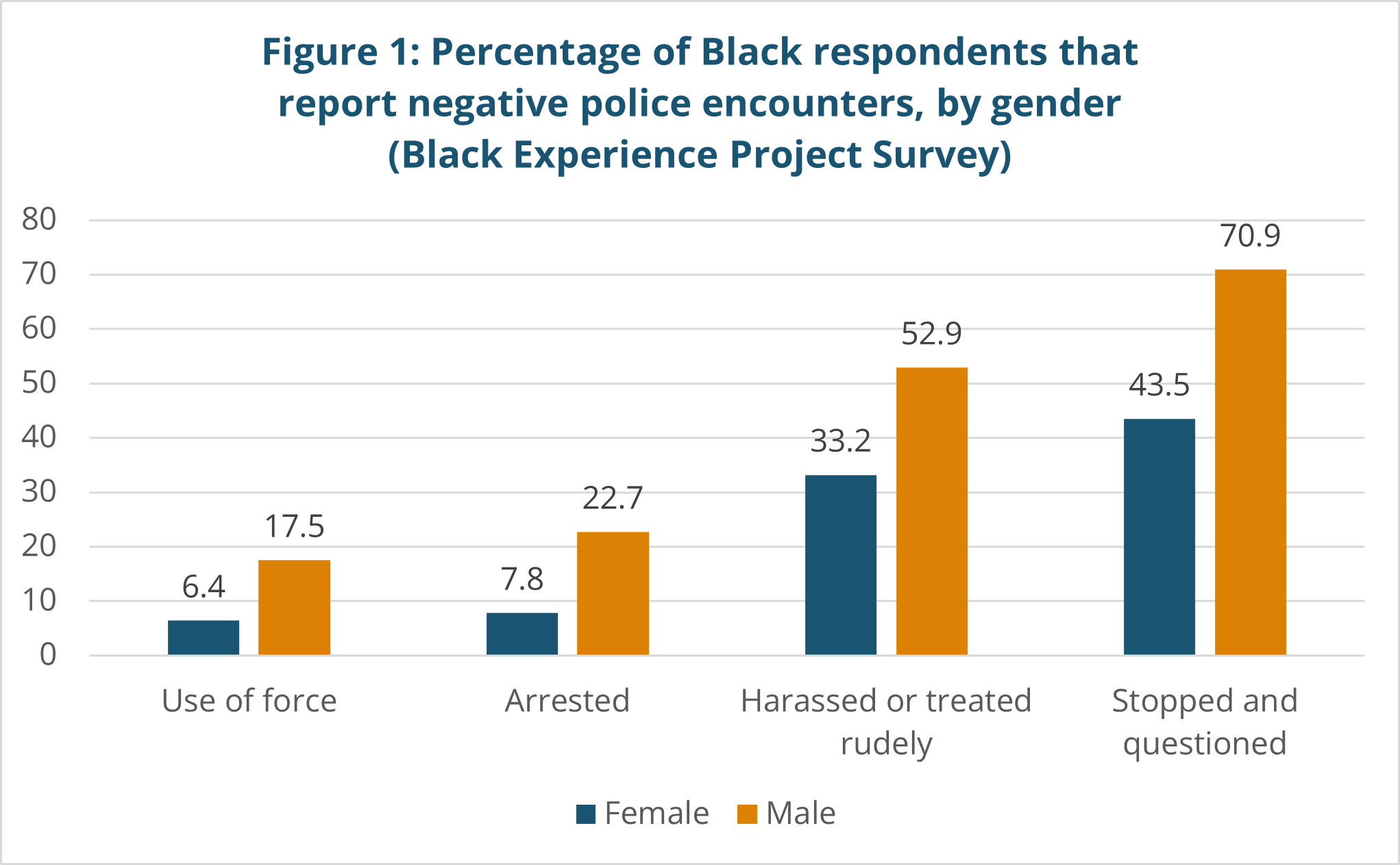

The issue of involuntary police contact was also explored by a survey conducted as part of the Black Experience Project (Environics Institute 2017). This survey, conducted in 2015, explored the opinions and experiences of 1,504 Black residents, 16 years of age or older, from the Greater Toronto Area. My reanalysis of this data, obtained by the OHRC, confirms that negative encounters with the police are very common among the Black residents of the GTA – particularly Black men. For example, 71% of Black male respondents reported that they had been stopped and questioned by the police in a public place, 53% reported that they had been harassed or treated rudely by the police, 23% had been arrested by the police at some time in their life, and 17.5% reported that they had been subject to police use of force (see Figure 1).[13]

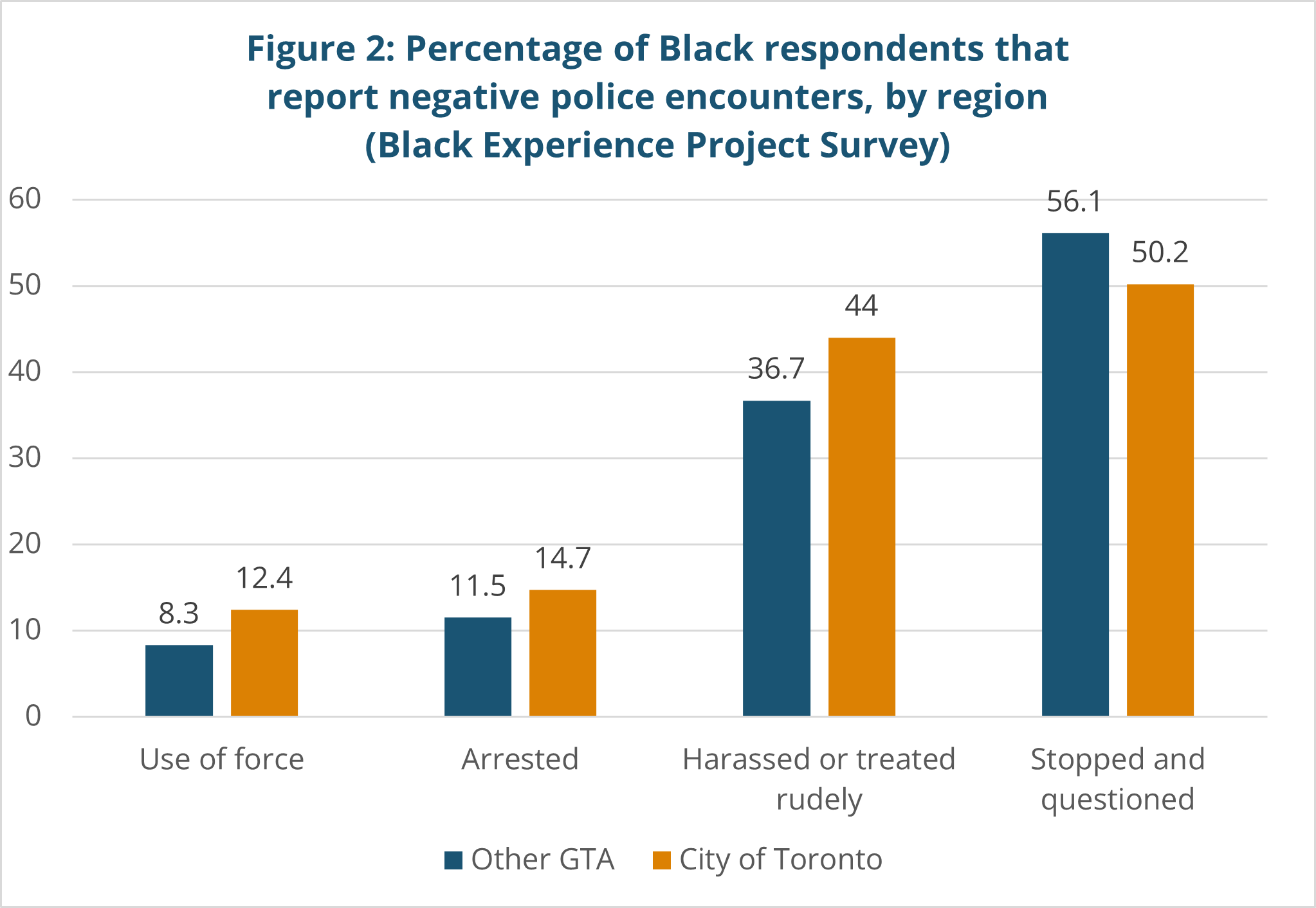

The data further reveal that negative police experiences are slightly more common among Black residents of the City of Toronto than respondents who live in other areas of the GTA (see Figure 2). For example, Black Toronto residents are more likely to report police

use of force, being arrested by the police and being harassed or treated rudely by the police. However, other GTA residents are slightly more likely to report that they have been stopped and questioned by the police in public. Unfortunately, the data do not allow for an examination of where police stops took place. It is quite possible, therefore, that some respondents who live outside of Toronto were actually stopped by the Toronto Police when travelling through the city for work or leisure. All regional differences are statistically significant at the p >.05 level.

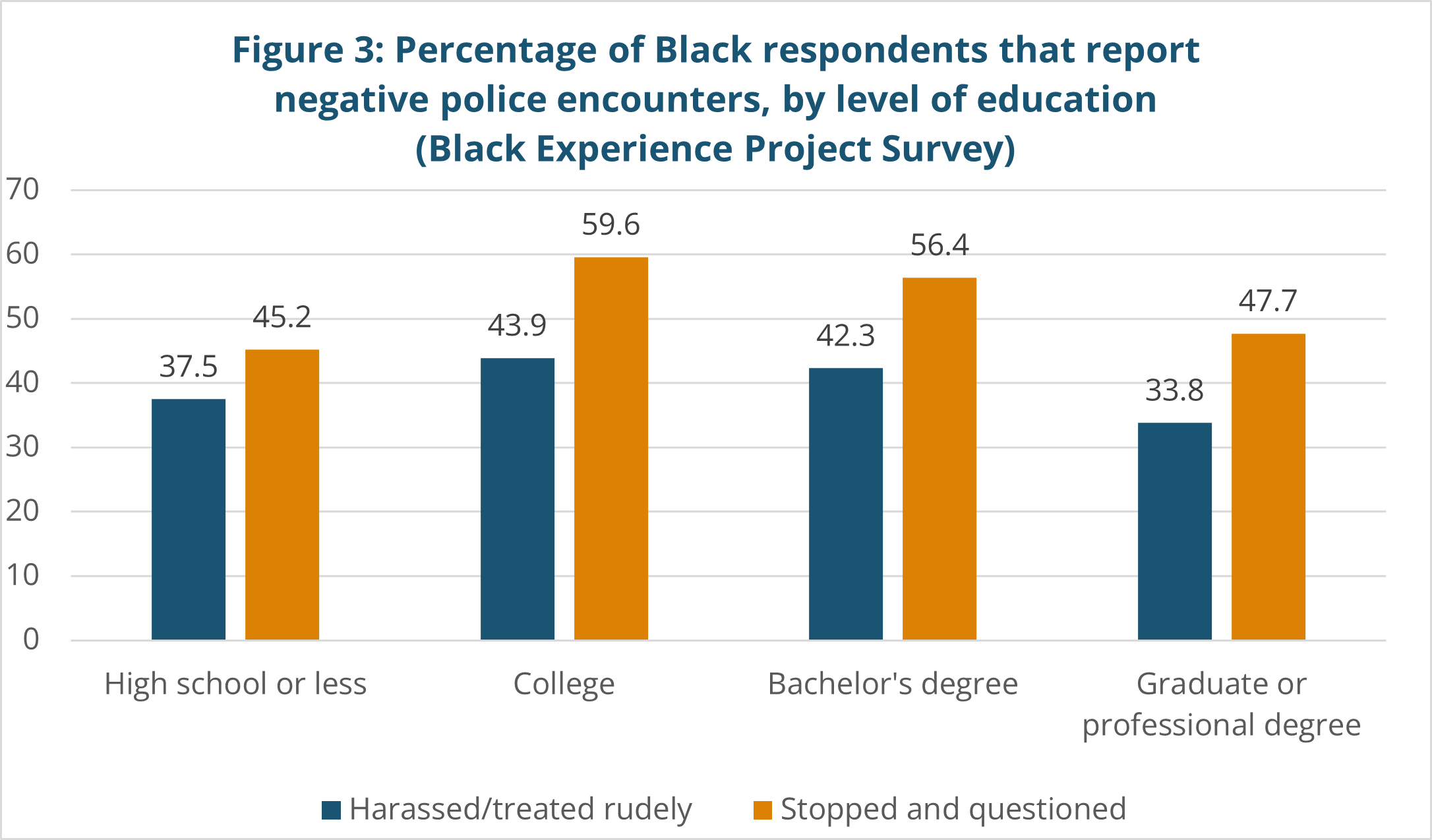

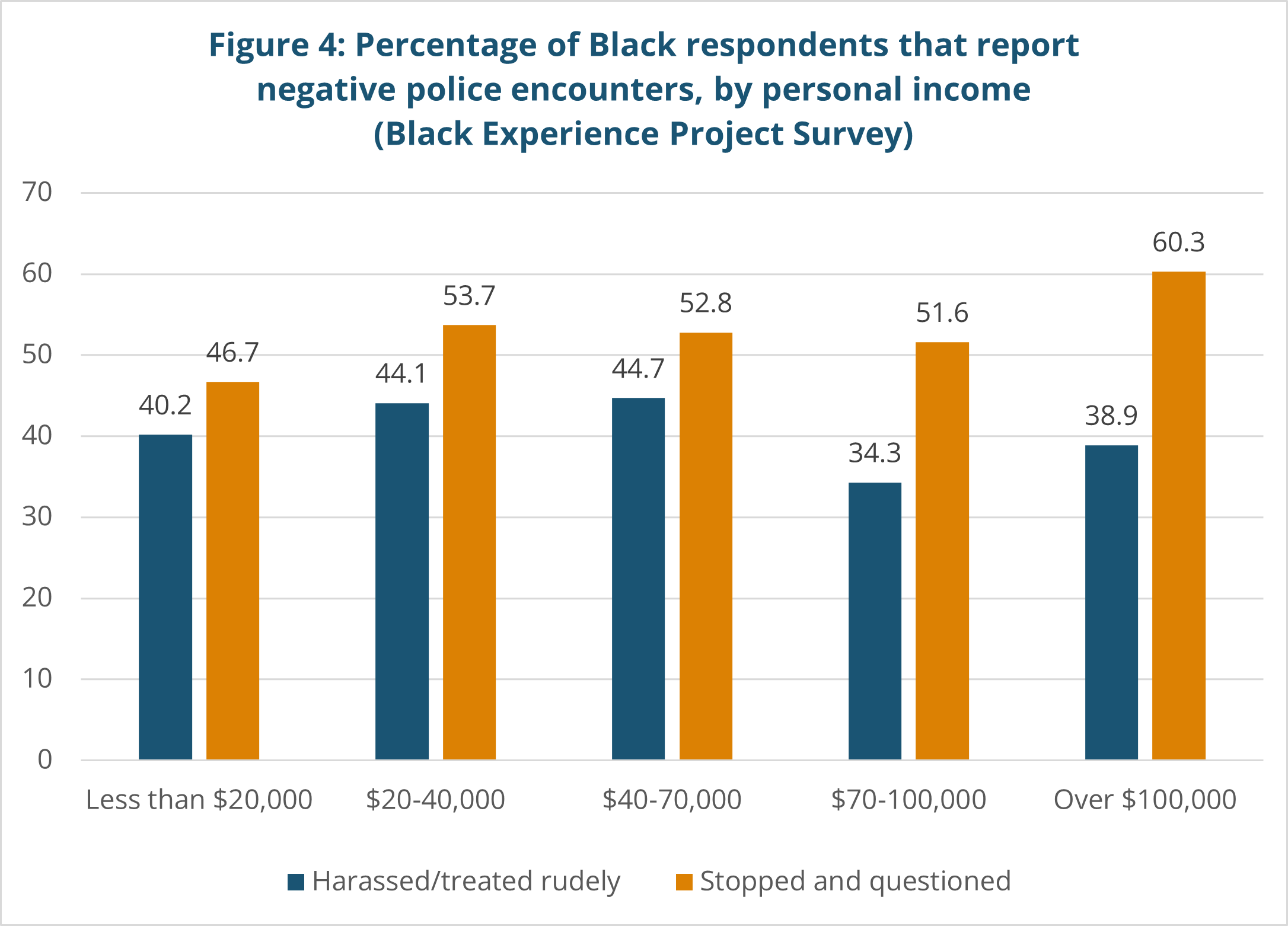

In the past, critics have argued that it is poverty or lower-class position, not racism, that exposes Black people to negative police encounters. However, consistent with previous studies, the results of the Black Experience Project reveal that higher social-class position does not protect Black people from involuntary police contact (see Figures 3 and 4) For example, Black people with an undergraduate university degree are more likely to report being stopped and questioned by the police (56.4%) than people with a high school degree or less (45.2%). Similarly, respondents who earn $100,000 or more per year are more likely to report being stopped and questioned by the police (60.3%) than respondents who earn less than $20,000 per year (46.7%). These differences are statistically significant. These findings further strengthen the argument that race alone draws police attention, not social class or residence in a poor neighbourhood.[14]

Summary

With respect to investigating racial profiling, survey research has three distinct advantages over qualitative data. First of all, since surveys are based on large, random samples, research results can be more easily generalized to the total population. Secondly, surveys permit direct comparisons between people who report that they have been stopped and searched by the police and people who have not been stopped. Thus, we are able to determine if people who are frequently stopped and searched by the police are different – with respect to race or other theoretically relevant factors – than people with little or no contact. Finally, in addition to documenting specific experiences with the police, surveys can also be used to investigate the psychological impact that perceived racial profiling incidents have on targeted populations.

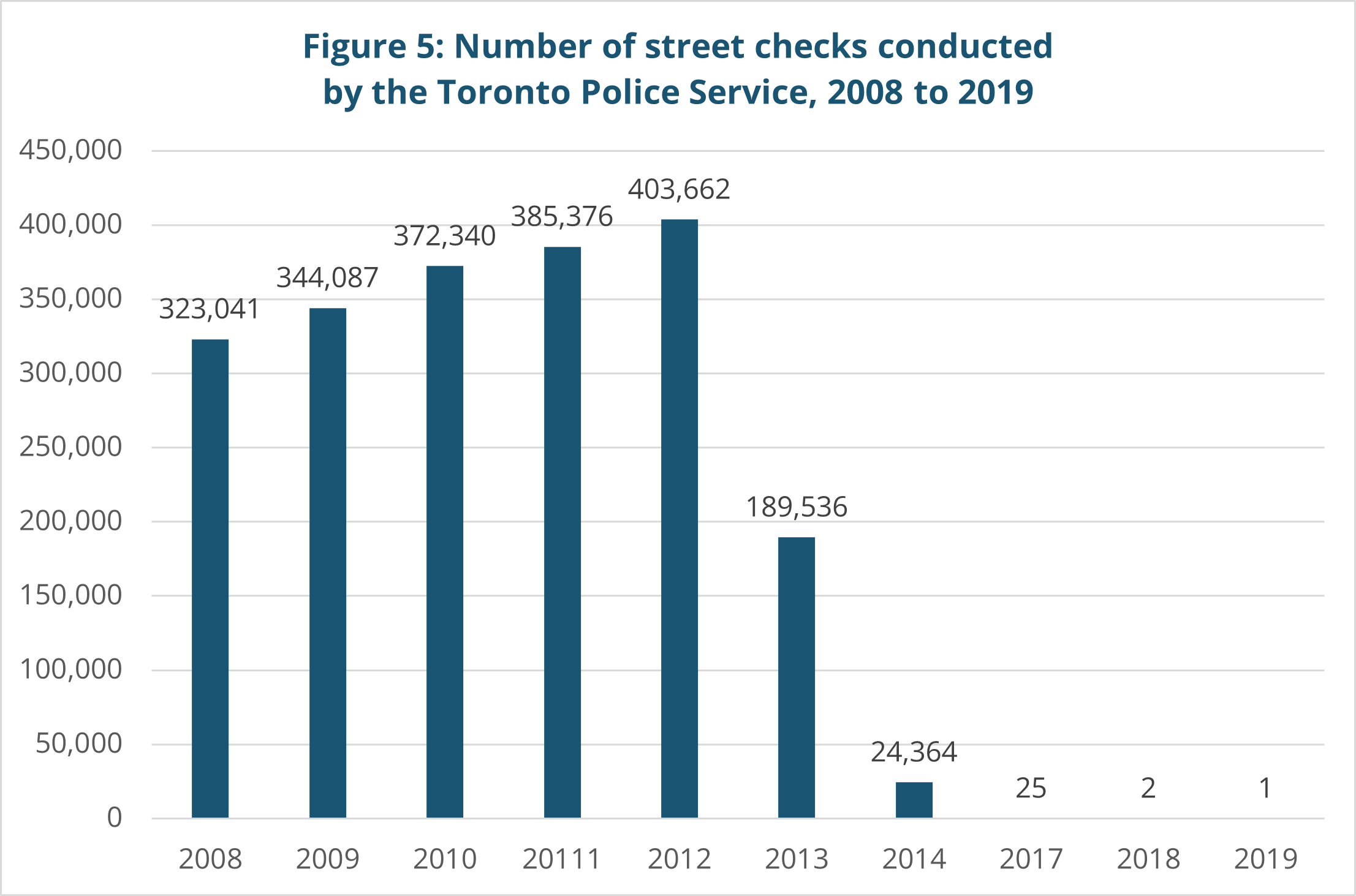

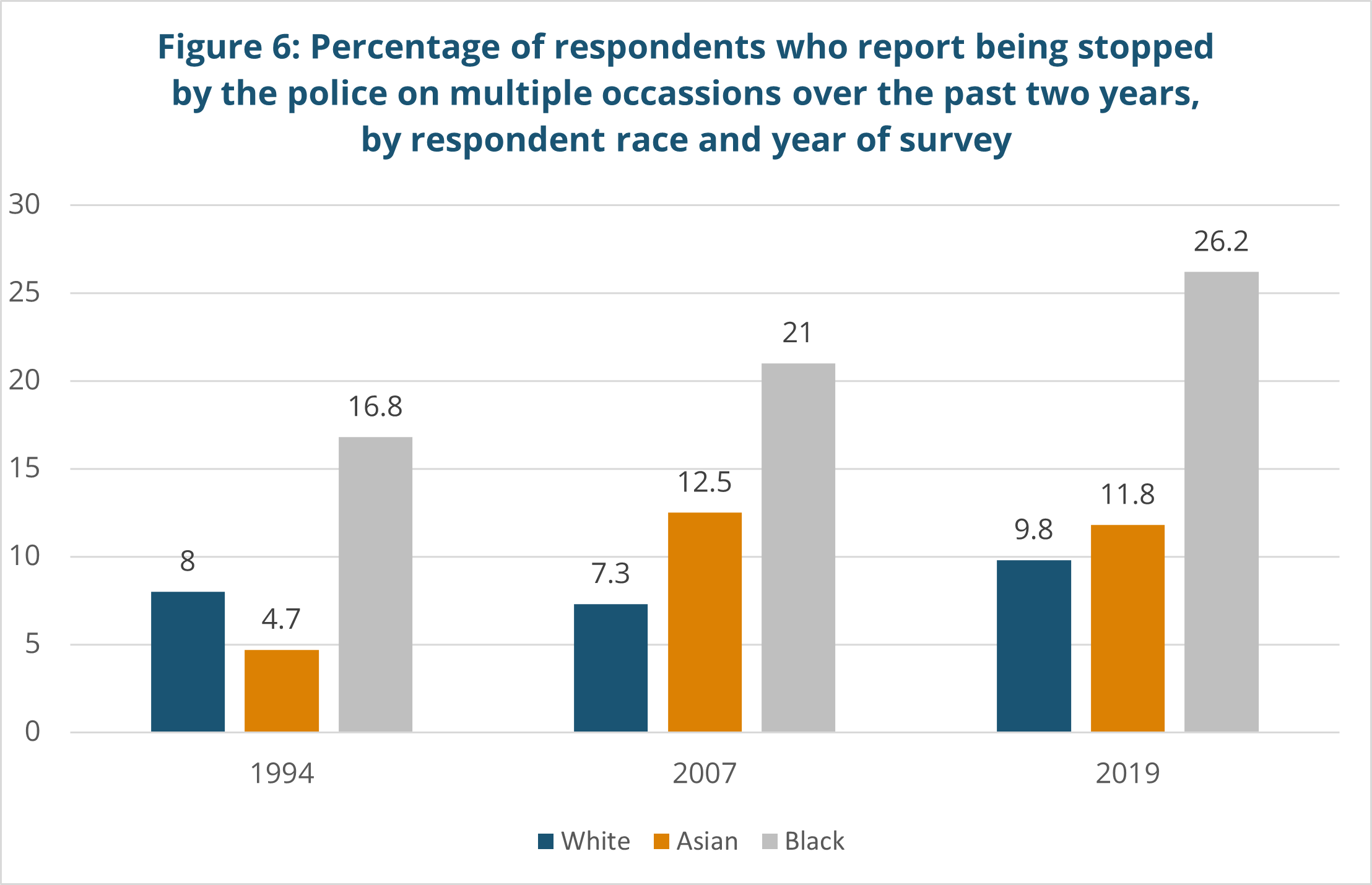

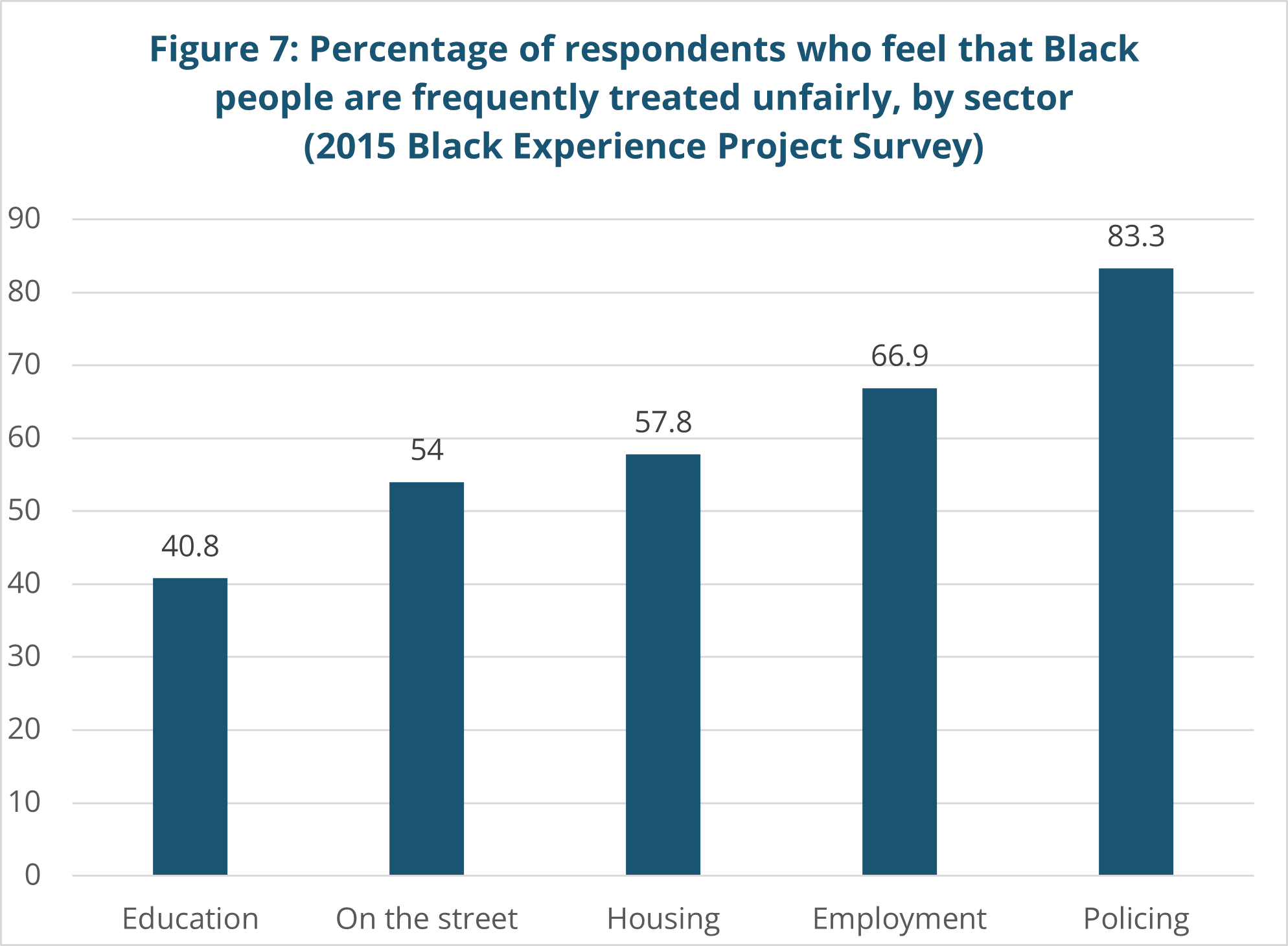

Survey research, however, is not without its limitations. Potential weaknesses with survey methods include problems with sampling error, questionnaire construction, respondent recall, respondent honesty and sample exclusion (see Lichenberg 2007; Lundman 2003). However, comparing the results of surveys with the results of other qualitative and quantitative research methods can serve as a validity check and ultimately increase confidence in the findings. It is thus important to note that the results of the above Toronto-area surveys are remarkably similar to the results produced by qualitative studies (see discussion above) and studies that examine official statistics from the Toronto Police Service. We turn to an analysis of official TPS “street check” data in the next section.