Human rights and creed research and consultation report

I. Introduction

1. Setting the context

Since the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) published its Policy on creed and the accommodation of religious observances (Policy on creed) in 1996, there have been significant legal and social developments in Canada and internationally that have shaped the experiences of communities identified by creed. There is also extensive public debate about the appropriate scope and limits of human rights protections for religion and creed in Ontario society.

The OHRC is currently updating its 1996 Policy on creed to reflect these developments. The goal is to clarify the OHRC’s interpretation of human rights based on creed under the Ontario Human Rights Code (the Code) and advance human rights understanding and good practice in this area. The update, which began in 2011, will take two to three years to finish. It will involve extensive research and consultation, and will draw on lessons learned from the OHRC’s recent work on the Policy on competing human rights.

To date, the OHRC has hosted two major consultation events, including:

- A policy dialogue on human rights, creed and freedom of religion on January 12 – 13, 2012 at the University of Toronto’s Multi-Faith Centre, in partnership with the University of Toronto’s Religion in the Public Sphere Initiative and Law School

- A legal workshop on human rights, creed and freedom of religion on March 29 – 30, 2012 at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School, in partnership with York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School, Centre for Public Policy and Law and the Centre for Human Rights.

We then published selected policy dialogue papers in a special issue of Canadian Diversity. These papers, along with those from the legal workshop, are available on the OHRC website at www.ohrc.on.ca.

The OHRC has also done extensive research internally, including:

- A Creed case law review

- An environmental scan and literature review

- Review and analysis of 2010/11 and 2011/12 fiscal year applications currently at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO).

The OHRC will be engaging in further research and public consultation in 2013-2014, in part based on responses to the Human Rights and Creed Survey, and feedback from a forthcoming Human Rights and Creed Research and Consultation Report that will be posted on the OHRC’s website in the Fall of 2013.

2. The purpose of this report

The primary aim of this paper is to report on OHRC research and consultation findings and analysis to date on key creed-based human rights issues, options and debates. We hope that this will add further transparency to our creed policy update process, and help to increase general public awareness of creed-based human rights issues. Another goal is to develop a stronger contextual framework for understanding and addressing contemporary creed-based human rights issues.[1]

We welcome and encourage your feedback on the questions and content of this report. Please email your comments to creed@ohrc.on.ca. Your feedback is valued and will help to guide us as we update the creed policy in the coming year.

3. Criteria for assessing and developing human rights policy

When developing and assessing policy issues, options and positions, the OHRC considers the following criteria:

(a) An interpretation of the Code that protects, promotes and advances the purpose of human rights legislation in Ontario[2]

The Preamble to the Ontario Human Rights Code elaborates four key principle goals of the Code: (i) recognizing the dignity and worth of every person; (ii) providing equal rights and opportunities without discrimination that is contrary to law; (iii) creating a climate of understanding and mutual respect, so that; (iv) each person feels a part of the community and able to contribute fully to the development and well-being of the community and the province.

(b) The OHRC’s mandate to promote and advance respect for human rights in Ontario, to protect human rights in Ontario, and to identify and promote the elimination of discriminatory practices[3]

The Commission strives for objective, principled and informed policy development.

(c) Canadian and international human rights law, legal decisions and principles for statutory interpretation[4]

OHRC policies may advance and broaden interpretations of the Code. However, they should not contradict clear legal precedents for interpreting the Code at the time of their publication.

[1]This in part recognizes that courts and tribunals are increasingly relying more on looking at context when analyzing discrimination, and relying less on abstract formal analyses.

[2] The courts have affirmed that human rights legislation, including the Code, should be given a liberal and purposive interpretation, in keeping with its quasi-constitutional status. The higher courts have also provided details on the purposes of human rights statutes, also discussed in Section IV. 2.1.5.

[3] As stated in Section 29 of the Code.

[4] Relevant principles of statutory interpretation are considered in Section IV. 2.1. International laws and instruments that are relevant to developing creed policy include, but are not limited to the: (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR); (1966) International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPRD); (1966) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); and (1981) Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination based on Religion or Belief.

II. Executive summary

Background trends

The Ontario Human Rights Code focuses on prohibiting discrimination in five protected social areas: employment; housing; goods, services and facilities; contracts; and vocational associations. Part of the OHRC’s role is to create policies that give the details for making this vision a reality.

To create relevant and responsive human rights policy, the OHRC needs to identify and understand past and present social trends and dynamics that contribute to contemporary forms of discrimination based on creed. This understanding helps the OHRC combat prejudice and intolerance, reduce tension and conflict, and address the root causes of discrimination in Ontario.

Research shows that there is growing religious and creed diversity in Ontario. While most Ontarians continue to identify as Catholic or Protestant, census data reveals particularly significant growth among religious minority groups outside of the historical Christian (Catholic and liberal Protestant) mainstream churches. Immigration accounts for much of this deepening religious diversity.

A growing number of Ontarians also report that they have ”no religion.” As well, increasing numbers of people of all faiths are living and practicing their faith in more individualized ways, detached from institutional structures and conventions. For instance, it is becoming more common for individuals and families to practice two or more religious/creed-based belief systems. All of these broader trends are projected to accelerate in the future.

Some of these trends are fairly recent. At least up until the 1960s, Canada was commonly viewed as a “Christian nation.” The state extended special privileges to a small number of Christian (mainly English Protestant and French Catholic) denominations. Christian Canadians played a central role in building many of Ontario’s current institutions, which people of all faiths continue to benefit from today. However, over this same period, religious minority groups regularly faced persecution and discrimination. Perhaps the most egregious example of historical efforts to assimilate non-Christian “others” was the forced Christian residential schooling of Aboriginal children in Ontario (see the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s publication, They Came for the Children, available for download on the TRC website at www.trc.ca).

Since the 1960s, public policy and law has increasingly come to celebrate and embrace diversity, equality and non-discrimination. This has been accompanied by a new more secular approach in public life and state institutions. Many historic Christian privileges in public institutions have since been challenged and removed, as religion has generally become more privatized. At the same time, legal protections for creed and freedom of religion have increased since the Ontario Human Rights Code was introduced in 1962 and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982.

Hate crime statistics and social research show that prejudice and discrimination based on creed remain a stubborn problem in Ontario, and one that is growing in some cases. Over the past 20 years, newer forms of racism, antisemitism and Islamophobia have emerged, sometimes drawing on and reviving older (in some cases racialized) stereotypes. At times, this has led to the indiscriminate targeting of victims based on “perceived creed.”

Discrimination and prejudice targeting Muslims has been particularly pronounced in the post-911 period. This is reflected in Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO) complaints (called applications). Muslims were the most over-represented creed group among HRTO applicants, accounting for more than one-third (36%) of all HRTO applications citing creed in the 2011-12 fiscal year. Antisemitism, discrimination and hate crimes against Jewish people also continue to be a problem. A study by the League for Human Rights of B'nai Brith[5] said that antisemitic incidents more than doubled in the past 10 years. Some 10.7% of all HRTO complaints citing creed as a ground in the 2011-12 fiscal year involved persons self-identifying as Jewish (second highest among creed groups, when different Christian denominations are considered as separate groups).

Research also suggests that Aboriginal Peoples continue to face significant barriers practicing Ontario’s longest standing spiritual traditions, which are often misunderstood or inadequately recognized by institutional authorities as warranting accommodation. Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs also spoke of facing various barriers to their religious accommodation in OHRC consultations to date. Due to the actual and/or perceived close relationship between ethnicity and religion, experiences of creed discrimination by some members of these communities were sometimes compounded by various forms of racism and xenophobia. Members of newer, smaller and lesser-known faith communities, as well as atheists, agnostics and people without any religious affiliation, also spoke of facing various forms of stigma, prejudice and discrimination.

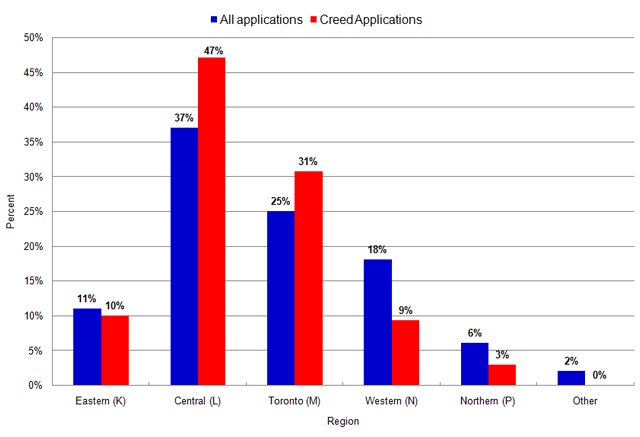

HRTO applications filed between 2010 and 2012 show that a majority of human rights applications involved claims of discrimination in employment. Most applications were filed in the central region, clustering around the Greater Toronto Area in particular. An overwhelming majority of HRTO applications citing creed over this period also cited a race-related ground (such as race, ancestry, colour, ethnic origin, place of origin) as an intersecting basis of discrimination. While applications citing creed accounted for 6.8% of all applications filed at the HRTO in the 2011-2012 fiscal year, this number likely does not reflect the full extent of discrimination based on creed actually occurring in Ontario over this period, due to such factors as under-reporting, mis-reporting and the unknown outcome of applications.

Religious and creed communities also continue to encounter less obvious, but equally significant, structural forms of discrimination and inequality. In some cases, this is a result of the differential impact on creed communities of past religious privileges and norms in society, as these play out in the present. In other cases, it is a result of newer and more aggressive and ideological “closed” forms of secularism that seek to shut out all forms of religion from public life, ironically in the name of keeping the public sphere “neutral.” In this context, a growing number of Christian Ontarians have spoken about feeling increasingly marginalized, as “minorities” in the current environment, including people affiliated with denominations that form a numeric majority in this province. This is reflected in HRTO complaints citing creed as a ground of discrimination. Over a third of these were filed by persons from Christian denominations in the 2011-12 fiscal year (next only to Muslims, among creed groups).[6]

While the reality on the ground can sometimes differ, Canadian courts have nevertheless made clear that the Canadian legal understanding of secular remains “open” and “inclusive” of religion, which means accommodating, and neither favouring nor disadvantaging or excluding, religion in the public sphere, in keeping with the Charter and Code.

What is creed?

“Creed” is one of the Code’s prohibited grounds of discrimination. The Code does not define it, but the OHRC defined the term creed in its 1996 Policy on creed and the accommodation of religious observances as “religious creed” or “religion,” broadly conceived. While every Ontarian, according to the 1996 policy, has a right to be free from “discriminatory or harassing behaviour that is based on religion or which arises because the person who is the target of the behaviour does not share the same faith” (including atheists and agnostics), the same policy goes on to state that creed “does not include secular, moral or ethical beliefs or political convictions.” The 1996 policy also states that creed human rights protections do “not extend to religions that incite hatred or violence against other individuals or groups, or to practices and observances that purport to have a religious basis but which contravene international human rights standards or criminal law.”

Since the OHRC’s 1996 policy, courts and tribunals have increasingly had to grapple with what qualifies for human rights protection on the ground of creed. Several recent cases have involved non-religious belief systems, including ethical veganism,[7] atheism[8] and political belief.[9] This and other legal considerations and social trends (including the significant growth of Ontarians identifying as having no religion,[10] and potentially deriving moral direction and meaning in life from non-religious belief systems) have helped to bring the question of defining creed to the forefront of the current policy update.

Most tribunal and court decisions have interpreted creed as the same as “religion,” in keeping with the OHRC’s 1996 policy position. However, other decisions have left open the possibility that non-religious beliefs may be a creed under the Code. Overall, the courts appear to be reluctant to offer any final, authoritative, definitive or closed definition of creed. Instead, they prefer a more organic, analogical (“if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it must be a duck”) case-by-case assessment.

Courts and tribunals have also recognized a wide variety of religious and spiritual beliefs under human rights legislation and the Charter, including Aboriginal spiritual practices,[11] Wiccans,[12] Raelians[13] and Falun Gong[14] practitioners. There appears to be nothing in the Code-based case law that would prevent the OHRC from redefining creed more broadly and inclusively in its updated policy.

Indeed, the use of the term “creed” rather than “religion” in the Code may suggest that they are meant to have different meanings. The courts have nevertheless offered some guidelines on the outer limits of what they will recognize under the Code ground of creed (see the Creed case law review).

Creed accommodation

The duty to accommodate creed beliefs and practices is well established in Ontario human rights law. Organizations governed by the Code also have a responsibility to design services, programs and employment systems inclusively so that all Ontarians can equally benefit and take part in them. Putting such ideals into practice, however, can be challenging for organizations.

To comply with the Code duty to accommodate creed beliefs and practices, there are challenges when determining:

- sincerity of belief

- the extent and scope of the duty to accommodate, and to inclusively design for, creed beliefs and practices

- how to accommodate group-based creed observances

- appropriate accommodation arrangements, processes, roles and expectations for accommodation providers and seekers.

Common types of accommodation based on creed, where issues can arise, include:

- Providing days off for Sabbaths and religious holy days

- Providing time and space for prayer

- Modifying dress codes and safety requirements to accommodate religious attire and the wearing of religious objects (such as wearing a headscarf in sporting events)

- Providing exemptions and alternatives to photo and biometric identification

- Providing acceptable food options

- Exempting individual employees and service providers from tasks that violate their religious conscience (for example, serving alcohol, providing blood transfusions, etc.).

The OHRC is interested in hearing more about the practical challenges individuals and organizations face when accommodating creed beliefs and practices, and any other accommodation challenges you think should be addressed in the updated policy.

[5] B’nai-Brith. 2012 Audit of Antisemetic Incidents. National Executive Summary. Retrieved July 24, 2013 from www.bnaibrith.ca/audit2012/.

[6] Among Christian denominations, people self-identifying as “Roman Catholic” or simply “Christian” in their application accounted for the largest number of Christians filing human rights applications at the HRTO in the 2011-12 fiscal year (both 9.3 % each), followed by people self-identifying as Seventh Day Adventist (5.7%) and Christian Orthodox (2.9%).

[7] See Ketenci v. Ryerson University, 2012 HRTO 994 (CanLII).

[9] Al-Dandachi v. SNC-Lavalin Inc., 2012 ONSC 6534 (CanLII).

[10] According to the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), by 2011, almost one-quarter of Ontario residents (23%) were religiously unaffiliated, compared to 5% in the 1971 census.

[11] See Kelly v. British Columbia (Public Safety and Solicitor General) (No. 3), 2011 BCHRT 183 (CanLII).

[12] Re O.P.S.E.U. and Forer (1985), 52 O.R. (2d) 705 (C.A.).

[13] Chabot c. Conseil scolaire catholique Franco-Nord, 2010 HRTO 2460 (CanLII).

[14] Huang v. 1233065 Ontario, 2011 HRTO 825 (CanLII).

III. Background and context

This section examines broader underlying trends shaping contemporary forms of discrimination because of creed. While the OHRC seeks to combat prejudice and intolerance based on creed, and related -isms and -phobias, by educating the public, not all of the issues discussed below can be dealt with under the Code. The Code only prohibits incidents of discrimination and harassment based on creed in specified “social areas.” These areas are:

- Contracts

- Employment

- Goods, services and facilities

- Housing

- Vocational associations and trade unions.

Intolerance vs. discrimination

Intolerance and prejudice refer to attitudes, values and beliefs. Discrimination refers to actions taken because of those attitudes, values and beliefs, as well as unfair treatment that may unintentionally result from seemingly neutral rules, norms, standards and practices that people can take legal action on under the Ontario Human Rights Code or Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Key questions

-

What are some of the significant factors and dynamics, past or present, that shape contemporary forms and experiences of discrimination based on creed in Ontario?

-

What forms of exclusion and discrimination are communities in Ontario experiencing because of creed?

-

Are there particular or prevalent ideologies, myths, and/or stereotypes underlying contemporary forms of discrimination based on creed that an OHRC policy should name and address?

1. Current social and demographic trends

1.1 Diversity of creed beliefs and practices

Canadian census-based demographic research on religious affiliation in Ontario shows a significant growth in religious and creed diversity. Two major trends are particularly notable. First, there is significant growth among religious minority groups of all kinds outside of the Christian (Catholic and liberal Protestant) mainstream (see Appendices 1-7) for statistical trends by religious affiliation in Ontario and Canada).[15] At the same time, there is notable growth in the numbers of Ontarians reporting that they have ‘no religion’ (see Appendices 1-5, 12-15)[16] and/or for whom religion is playing a decreasing role in their lives (see Appendices 16-21). Both of these broader trends are projected to accelerate in the future,[17] due in part to immigration trends[18] and ongoing processes of secularization.

An overwhelming majority of Ontarians nevertheless remain, and are projected to remain, identified with the historically dominant Roman Catholic and Protestant (Anglican, United Church, Presbyterian, and Lutheran) churches in Ontario (see Appendix 3).[19] The face and practice of Canadian Christianity, however, is becoming increasingly more diverse, as the percentage of Christian Canadians born in non-Western countries continues to grow,[20] along with the numbers of adherents of minority Christian denominations favouring more public and collective expressions of Christianity.

Tracking religion in Ontario 1991 – 2001 - 2011

The largest population growth in Ontario between 1991 and 2001 censuses has been among Muslims (142.2% growth from 145,560 in 1991 to 352,530 in 2001), minority “Christian’” Protestant groups including people identifying as “Christians,” ”Evangelical,” ‘Born-again Christian” and “Apostolic” (121.2% growth from 136,515 in 1991 to 301,935 in 2001), Hindus (103.9% growth from 106,705 in 1991 to 217,560 in 2001), Sikhs (109.2% growth from 50,085 in 1991 to 104,785 in 2001) and Buddhists (96.4% growth from 65,325 in 1991 to 128,320 in 2001). The top five religious denominations in Ontario in 2001, in order of their numbers include: Protestant (3,935,745), Roman Catholic (3,866,350), No religion (1,809,535), Muslim (352,530), and Christian, including people identifying as minority Christian groups as listed above (301,935). National census data also reveals significant growth nationally, between 1991 and 2001, of people identifying with Aboriginal spirituality (+175%), or as “pagan” (+281%), although the actual number of adherents is not over 30,000 in these categories. [Source: Statistics Canada 2003a; see Appendices 1-11 for further profile and breakdown of Canadians by religious affiliation]

Though not entirely comparable with, or as reliable as, earlier census data, the 2011 National Household Survey shows continued significant growth, since 2001, of religious minorities, including Sikhs (72% growth from 104,785 in 2001 to 179,765 in 2011), Hindus (68% growth from 217,560 in 2001 to 366,720 in 2011), Muslims (65% growth from 352, 530 in 2001 to 581,950 in 2011), No religion (62% growth from 1,809,535 in 2001 to 2,927,790 in 2011), and Buddhists (28% growth from 128,320 to 163,750 in 2011).

Religious affiliation in Ontario in descending order by numbers and percentage (2011 National Household Survey) [21]

|

Religion |

Population Number |

Percentage |

|

1. Catholic |

3,976,610 |

31.43% |

|

2. No religious affiliation |

2,927,790 |

23.14% |

|

3. Other Christian |

1,224,300 |

9.68% |

|

4. United Church |

952,465 |

7.53% |

|

5. Anglican |

774,560 |

6.12% |

|

6. Muslim |

581,950 |

4.60% |

|

7. Hindu |

366,720 |

2.90% |

|

8. Presbyterian |

319,585 |

2.53% |

|

9. Christian Orthodox |

297,710 |

2.35% |

|

10. Baptist |

244,650 |

1.93% |

|

11. Pentecostal |

213,945 |

1.69% |

|

12. Jewish |

195,540 |

1.55% |

|

13. Sikh |

179,765 |

1.42% |

|

14. Buddhist |

163,750 |

1.29% |

|

15. Lutheran |

163,460 |

1.29% |

|

16. Other religions |

53,080 |

0.42% |

|

17. Traditional (Aboriginal) Spirituality |

15,905 |

0.13% |

|

Total population in private households by religion |

12,651,795 |

|

Note: Unlike in previous decades, when a religion question was included in the census, in 2011 it was part of a voluntary survey among 4.5 million randomly selected households. Roughly 2.65 million households participated in the survey. Statistics Canada has indicated that some groups – immigrants, ethnic minorities, non-English or non-French speakers and Aboriginal Peoples – may be underrepresented among participants in the voluntary survey. Despite these challenges, the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) represents the best data source for religious affiliation in Canada in 2011 (Pew Forum 2013).

The total number of persons identifying as Christian (including all denominations) in the 2011 NHS was 8,167,295, or 64.55% of the total population. The number of persons identifying with Protestant denominations in the 2011 NHS, if we include “other Christian”, as well as United, Anglican, Presbyterian, Baptist, Pentecostal and Lutheran, was 3,892,965 or 30.77%. This would make Protestants the second largest religious grouping collectively, for the first time after Catholics.

1.2 Individual belief and practice

There is a debate in the social science literature about whether and to what extent religious conviction may be declining in Ontario (the “secularization debate”). Evidence exists to support various contending positions, showing both a general decline and, in some segments of the population, resurgence of religious conviction and identification (see Appendices 13-21 for various survey findings on the extent and importance of religious belief among Canadians).[22]

Ontarians, especially the younger generation, seem to be increasingly changing the way they interpret and live their professed religious and creed beliefs. Research suggests that many people now approach their religion or creed in a highly individual way, basing their beliefs and practices more on personal interpretations and experiences than on institutional expressions or traditional requirements of the faith.[23] This personalization of belief and practice has also contributed to a growing pattern of eclecticism – famously dubbed “Sheilaism”[24] by an American sociologist. This means that people increasingly “cobble together” their beliefs and practices from increasingly diverse sources and traditions in unique ways that can change with the context.[25]

This “de-institutionalization” of belief and practice is evident in the declining numbers of religiously-identified persons who are actively practising their faith in traditional institutional ways such as by attending regular worship (see Appendix 17).[26] The growth of persons self-identifying as “spiritual but not religious,” combined with the growing trend of Ontario institutions rebranding chaplaincy programs and services as “spiritual” rather than “religious”, are also among the indicators of this larger trend.

Spirituality vs. religion

Spirituality can be defined as “the search for meaning, purpose, and connection with self, others, the universe, and ultimate reality, however one understands it. It may, or may not, be expressed through religious forms or institutions.” Religion, on the other hand, tends to be “an organized structured set of beliefs and practices shared by a community related to spirituality” (Sheridan, 2000, p. 20; emphasis added).

1.3 Policy and program trends

"The challenges Canada faces today are different from those we faced ten years ago. The most obvious change concerns the salience of religion in debates about Canadian diversity ..." (Will Kymlicka) [27]

Despite increasing demands on Ontario institutions to better understand, respond to, and navigate the province’s growing religious/creed diversity, researchers lament the general failure of Canadian public policy, programming and research to sufficiently grapple with it.[28] While a legislative framework for dealing with creed diversity in Canada is well established,[29] researchers note that the prevailing tendency in policy and programming has been to subsume and erase differences of religion and creed under ethnic, cultural and racial categories of social difference, particularly since multiculturalism was introduced as state policy over 30 years ago.[30]

As a consequence, it has primarily fallen to the courts and tribunals to set the framework for dealing with religious and creed-based diversity in Canadian society, within a zero-sum (win or lose) legal system. In this context, the current work and role of the OHRC in updating its policy on creed takes on additional importance in helping citizens and organizations to negotiate differences and conflicts relating to religion and creed in a pro-active, principled way.

[15] A 2013 study of religious demographic trends in Canada by the Pew Forum found that Ontario has experienced the most significant increase in affiliation with minority religions among provinces in Canada (see Appendix 7). The share of Ontario residents who identify with faiths other than Protestantism or Catholicism has risen from about 5% in 1981 to 15% in 2011 (Pew Forum 2013).

[16] People identifying with no religion in Ontario in the 2001 census – 1,809,535 (or 16% of all Ontarians) – accounted for the third largest census denominational grouping after Protestant and Roman Catholic.

By 2011, according to the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), close to a quarter of Ontario residents (23%) were religiously unaffiliated, as compared to 5% in the 1971 census.

[17] See Appendix 8 for projected percentage change in religious affiliation in Canada from 2001 – 2017. According to the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), the number of Canadians who belong to non-Christian religions – including Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Eastern Orthodox Christianity – has already reached 11% in 2011, up from 4% in 1981 (Pew Forum 2013). Of note, much of this diversity is projected to be concentrated in Ontario’s largest cities.

[18] See Appendices 9, 10, and 11 for historical data on immigration trends by religious affiliation.

[19] The 2011 National Household Survey shows a small decline in the percentage of Ontario residents reporting to be Roman Catholic (31.4% in 2011 as compared to 34% in 2001, and 35% in 1991) and that a longer-term downward trend continues in the numbers of Ontarians who report to be Protestant (30.8% in 2011 as compared to 35% in 2001 and 43% in 1991), particularly among mainline Protestant denominations (Anglican, United Church, Presbyterian, Lutheran) (Statistics Canada, 2003a). Catholics overtook Protestants as the largest denominational grouping in Ontario for the first time in the 2011 NHS.

[20] The percentage of Christian Canadians born in non-Western countries continues to grow. As Beyer, 2008, p. 23 observes:

Thus, the 2001 census revealed that people who simply identified themselves as Christian or who said they belonged to small Protestant groups, mostly without a previous history in Canada, had grown much more rapidly over the decade (~30%, from about 1 to 1.3 million) than the Roman Catholics, the mainline Protestants (who declined by 10%), the established conservative Protestant denominations, or even the Eastern Christians. Those among these "other Christians" who were born in non-Western countries increased by over 100%, commensurate with the growth in non-Christian religions over the same period. Analogously, although Roman Catholics increased by only 4%, their absolute numbers increased by around 600,000; and people born in non-Western countries accounted for over one-third of this growth. Therefore, as global Christianity is demographically becoming more and more a religion of the "south" [citing Jenkins, 2007], so can we expect that Canadian Christianity will continue transforming in a corresponding fashion.

[21] Source: Statistics Canada. 2013. Ontario (Code 35) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Released June 26, 2013. www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed July 19, 2013).

[22] See Beyer (2006), “Religious Vitality in Canada: The Complementarity of Religious Market and Secularization Perspectives”.

[23] Roger O’Toole, 2006, p. 20 observes: “Canadians now choose to define the nature and content of their religiosity by drawing from that ‘reservoir of rites, practices and beliefs’ with which they are most familiar ‘without responding to any institutional prerequisites, or their consequences’. In these circumstances, their religion has generally acquired the fragmentary, syncretic, consumerist character associated with the term bricolage” (citing Yoye & Dobbelaere, 1993, p. 95-96). Based on their own empirical research, Peter Beyer (2008) and Paul Bramadat (2007) also observe how “[o]n the whole, youth of virtually all religious traditions are less loyal to these traditions and especially to the institutional expressions of these traditions (churches, mosques, temples, gurdwaras, etc.) than their age cohorts have probably been for many centuries if not millennia” (Bramadat, 2007, p. 120).

[24] In Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life, Robert Bellah et al. (1985), coined “Sheilaism” to refer to a broader late 20th century trend in American religious conviction. Sheila Larson was a nurse whose self-defined faith included included being kind and gentle with yourself, taking care of others, believing in God, but without going to church, and seeing Jesus in oneself. For more on this trend in Canada, see Bramadat (2007); Beyer (2008); Closson James (2006); and O’Toole (2006).

[25]In this respect, Reginald Bibby, 1987, p. 85 argues that "[t]he gods of old have been neither abandoned nor replaced". Rather “they have been broken into pieces and offered to religious consumers in piecemeal form". Religious scholar, Closson James, 2006, p. 130 similarly concludes that “we should expect [religion] to continue to be characterized more by an eclectic spirituality... cobbled together from various sources rather than a monolithic and unitary superordinating system of beliefs”. The growth of mixed faith marriages in Ontario is also contributing to people adhering to more than one faith tradition at the same time, sometimes depending on the context. “In 2001,” one article notes, “nearly 20 per cent of people married someone outside their faith, according to Statistics Canada, up from 15 per cent two decades ago. Of that 20 per cent, Jews and Christians were the most likely to be in inter-religious unions...More than half of inter-religious unions in Canada were between a Catholic and Protestant (Noor, 2013).

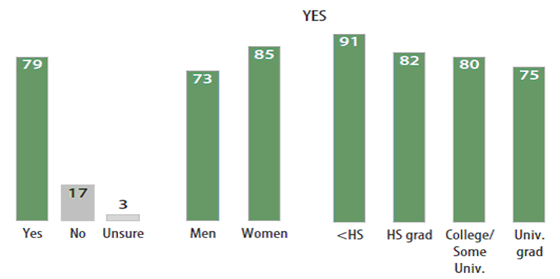

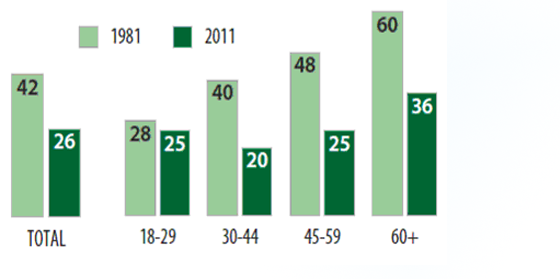

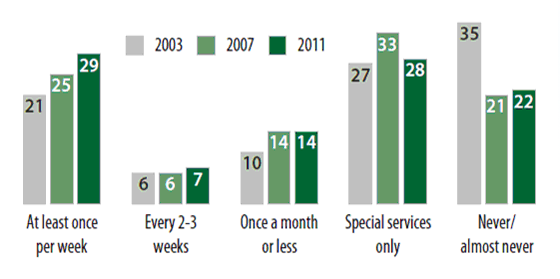

[26] Seljak et al. (2008) highlight the significant transformations that have occurred since the first Gallup Poll after World War II asked Canadians if they had been in a church or synagogue sometime during the previous seven days. A full 67% of Canadians said they had (including 83% of Catholics). By 1990, positive response to the Gallup question had fallen to 23% throughout Canada (see also Byer, 2008). More recently, a 2011 Environics Institute Focus Canada Survey found that “[a]lthough the proportion with a religious affiliation continues to drop, these Canadians are as observant as ever in terms of attending religious services. Three in ten (29%) say they attend services at least once a week (up from 25% reported in Focus Canada in 2007, and 21% in 2003), while fewer now doing so only for special services (e.g., Christmas mass, Jewish High Holidays) (28%, down 5 points from 2007). Another one in five (22%, up 1) continue to say they have a religious affiliation but never attend services, with this group most prominently represented by Quebec residents and Catholics. In contrast, weekly attendance is most widely reported by Evangelical Christians (56%) and members of non-Christian faiths (42%)” (Environics Institute, 2011, p.40; See Appendix 17 for 2011 Focus Canada Survey Findings on Frequency of Attending Religious Services Among Canadians With Religious Affiliation 2003-2011).

[28] One recent study of federal public servants from several departments and agencies in the National Capital Region found among other things that: most policy practitioners and public decision makers were ill equipped to deal with religious diversity and most policies and programs did not consider religious diversity, with a few exceptions (Gaye & Kunz (2009); see also Beaman (2008); Biles & Ibrahim (2005); Bramadat (2007); Seljak (2005).

[29] This legislative framework makes explicit reference to religion or creed as an important part of Canada’s celebrated diversity. It includes the (1982) Constitution Act’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the (1988) Multiculturalism Act, and provincial human rights statutes.

[30] Will Kymlicka (2008) speaks about the need to add religion into the multicultural policy mix as a ”third track” alongside ethnicity and race, noting a continuing “uncertainty about the role of religion within the multiculturalism policy, and about the sorts of religious organizations and faith-based claims that should be supported by the policy’” (cited in Kunz, 2009, p. 6). Scholars, seeing the reluctance to speak about religion as a public policy matter in Canada, describe religion as “a form of diversity that dares not speak its name” (Biles & Ibrahim, 2005).

2. Historical trends

2.1 Religion and state relations historically in Canada

Many scholars and commentators note a lack of historical awareness in current-day discussions of ”reasonable accommodation” and ”religion in public space.” This is especially the case when looking at the evolving ways that Canada has negotiated religious diversity and set its current secular approach. Scholars chart at least three main phases in Canada’s historic response to governing religious diversity. These move along a continuum from a single (Catholic and then Anglican) state-supported church with a virtual religious monopoly on public culture and institutions towards a more inclusive current-day secular, multicultural approach.

These eras have been generally described as:

1608-1841: European Catholics and Protestants sought to transplant their forms of Christianity to Canada through a state-supported Christian church, with little religious freedom.

1841-1960 Plural or shadow Christian establishment prevailed. While there was no official state church, there was a Christian culture and state cooperation with a limited number of “respectable” Christian churches (Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist/United, Baptist and Roman Catholic churches).

1960-present: Society became more secular, with greater “separation of church and state,” and an overtly multicultural approach to religion.[31]

Early efforts to establish an official state church in Lower and Upper Canada were largely frustrated by: (1) the practical challenges of extending parish administrative control over a vast and diverse territory with limited resources; and (2) the need for strategic compromises and political concessions in the face of the stubborn reality of religious pluralism on the ground, which has been a permanent feature of the Canadian social landscape. [32]

The new dominion of Canada that confederated in 1867 joined the mainly English-Protestant Upper Canada (Ontario) with French-Catholic Lower Canada (Quebec). Under the British North America Act, 1867, the new nation was bound by a uniquely Canadian compromise that remains with us today. This compromise does not establish any single state church, or require the separation of church and state.

Despite this early legal recognition of religious freedom in Ontario,[33] scholars have coined the term ”plural establishment”[34] or ”shadow establishment”[35] to describe the special privileges and government support and recognition extended to a limited number of mainline Anglo-Protestant (Anglican, Presbyterian and United) Churches and the French Roman Catholic Church. Other Christian denominations such as the Lutherans, Baptists and various evangelical groups also later joined the plural establishment’s “circle of respectability,” as “junior partners.”[36]

Many of Ontario’s most cherished contemporary institutions – including educational, healthcare and social service related – were created by Christian organizations in this era of “Christian Canada” (1841 – 1960). Today, many people do not recognize the central and formative role played by Christianity in building Ontario’s social, moral, legal and institutional fabric. A more recent body of work has emerged to highlight the positive contributions of religious actors and associations in Canadian history and society, particularly in building civil society and generating and contributing to “social capital” in Canadian society.[37] This key role continues to the present, and has contributed to Canada having, by some estimates, the second largest voluntary sector in the world (the largest segment of which is religion-based).[38]

2.2 Historical forms of discrimination based on creed

Advocating for the separation of Aboriginal children from their parents in Christian church-run residential schools, John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister, explained to the House of Commons in1883: “When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with his parents who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write.”

– (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012, p.6)

The history of the mainline Christian churches in Canada, however, also has a darker side that is sometimes forgotten. Scholars describe the emergence of a “Christian common sense” in Ontario between the mid-1800s and the 1960s, where “to be a (proper) Canadian, one had to be a (proper) Christian”.[39] Drawing such equations between race, religion, civilization and belonging led to extreme consequences, such as the assimilation policies and laws the Canadian government enacted to govern Aboriginal Peoples and cultures, particularly following the introduction of the Indian Act in 1876.[40]

Disparaging and legally suppressing Aboriginal spiritual practices and traditions was an integral part of the Canadian colonial project. Government and church authorities often worked hand in hand in this process. Only now, through the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, are Canadians starting to grapple with the ongoing, intergenerational impact of the concerted effort to “Christianize and civilize” the Indigenous peoples of Canada, which culminated in the residential school system administered by Christian churches between 1620 and 1996.[41]

Residential schools in Canada

- 1831 Mohawk Indian Residential School opens in Brantford, Ontario; it became the longest-operated residential school, closing in 1969

- 1847: Egerton Ryerson’s study of Indian education recommends religion-based, government-funded industrial schools

- 1857: Colonial government of Canada (including what is now Ontario and Quebec) passes Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in the Canadas

- 1860s: Assimilation of Aboriginal people through education becomes official policy

- 1876 Canada enacts first Indian Act

- 1884: Canadian Parliament outlaws the potlatch, the primary social, economic and political expression of some Aboriginal cultures

- 1892: Federal government and churches enter into partnership to run “Indian schools”

- 1951: Responding to international criticism, Parliament amends the Indian Act to remove anti-potlatch and anti-land claims provisions

- 1963: Federal government undertakes an “experimental” project by sending at least six Inuit children to Ottawa to study, to gauge how they would assimilate

- 1969: Partnership between government and churches ends; government takes over residential school system, begins to transfer control to Indian Bands

- 1996: Last government-run residential school closes

- 2008: Government of Canada offers Residential School Apology.

While First Nation spiritual rituals were a primary target of colonizing efforts, racism and religious prejudice in Canada also took shape in persecution and discrimination against Sikhs, Hindus, Buddhists (among other Chinese and Japanese religious practitioners), Muslims, Jews and other non-conforming groups, including disfavoured Christian minorities, atheists and agnostics.

After Aboriginal Peoples, Jews formed the largest non-Christian religious minority group in Canada, historically. Jewish communities have experienced antisemitic[42] prejudice, discrimination and, in some cases, violence since their arrival in the 1700s. Some egregious examples of this history include:

- The expulsion of Ezekiel Hart (the first elected Jewish official) from the Ontario (Lower Canada) Legislative Assembly, despite his re-election to the Legislature of Lower Canada in 1807, because he could not take the oath of office “on the true faith of a Christian”[43]

- The extensive web of Jim Crow-like restrictions overtly barring Jewish people from various mainstream social, political, economic and cultural institutions in Ontario society well into the 20th century[44]

- Acts of hatred and violence against Jews, such as the well-known 1933 Christie Pits riots in Toronto. This conflict involved six hours of violence between Jewish and Christian youths, and was followed by setting Jewish synagogues on fire and other personal attacks against Jews in public spaces.

One of the lowest points in this Canadian history of antisemitism was Canada’s rejection, in some cases with fatal consequences, of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, due to widely held beliefs that Jews were racially and religiously inferior.[45] These beliefs led Canada to place Jews in ”non-preferred” immigrant categories. Despite such treatment, the Canadian Jewish community persevered, and went on to rise to the forefront of the fight for human rights and anti-discrimination legislation in Ontario in the post-War era.[46]

Canadian immigration policy also proved to be a key tool in thwarting the entry of other “undesirable” ethno-racial and religious minorities in the 19th and 20th centuries, often through indirect and seemingly benign ways. Among the more famous examples are: the introduction of the Chinese head tax with the Chinese Immigration Act[47] of 1885 following Chinese labourers building of the Pacific Railway; and the passage of the Continuous Journey Act[48] in 1908, which, in effect, barred the immigration of “Hindoos” (as all Indians were called at the time, no matter what their religion). Discrimination and hostility towards these Asian immigrant groups, scholars note, had significant religious elements.[49]

Atheists, agnostics, humanists and the non-religious were also persecuted during the era of ”Christian Canada.” In one famous case, the citizenship applications of an avowed atheist immigrant family (Ernest and Cornelia Bergsma) from the Netherlands were twice denied before being successfully granted in a 1965 Ontario Court of Appeal ruling. The judge presiding over the initial citizenship hearing at the Haldimand County Court in Cayuga, Ontario, on April 3, 1963, deemed the Bergsmas to not be of sufficiently good character, or suited to life in a “Christian country,” based on their professed atheism.[50] He also found them unable to comply with the required oath of allegiance.[51]

Scholars also note that a great deal of dominant group energy was expended battling enemies within the Christian camp – those deemed heterodox, at best, and heretical, at worst. In fact, for most of Canada’s history, the main defining religious differences were between Christian denominations (Catholic and Protestant in particular). Christian minorities outside the plural establishment’s “circle of respectability,” such as Mennonites, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, Hutterites, Eastern Orthodox and Evangelicals, also faced significant and persistent discrimination and prejudice.[52] This exclusion sometimes intersected with other forms of racism and prejudice against ”less desirable” classes and “races” of European immigrants.[53]

2.3 Evolving policy and legal protections for religion and creed

Most historical accounts of the evolution of religious freedoms in Canada note a fundamental shift in law, policy and social discourse in the post-WWII era (see Appendix 22 which charts historical, legal, policy and demographic shifts over this era).[54] Public policy and law, particularly since the 1960s, has increasingly come to embrace values of diversity, equality and non-discrimination.[55] A new “secular” consensus has also contributed to the progressive privatization of religion and de-privileging (or “dis-establishment”) of Christianity in public and state institutional life.[56] The introduction of the Ontario Human Rights Code (the Code) in 1962 and, some 20 years later, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), both reflect and have helped to further entrench such “sea changes” in Canadian public values and culture.[57]

An example of the “sea change”

One historian captures this “sea change” in Canadian public culture by comparing the installation of the 19th and 27th Governors-General of Canada:

On September 15, 1959, Georges Vanier was installed as Canada's 19th Governor-General, the Queen's formal representative in her Canadian dominion. Vanier, a much decorated general, diplomat, and active Roman Catholic, began his acceptance speech like this: "Mr. Prime Minister, my first words are a prayer. May Almighty God in his infinite wisdom and mercy bless the sacred mission which has been entrusted to me by Her Majesty the Queen and help me to fulfill it in all humility. In exchange for his strength, I offer him my weakness. May he give peace to this beloved land of ours and, to those who live in it, the grace of mutual understanding, respect and love."

Fifty-six years later, on September 27, 2005, Michaëlle Jean became the 27th Governor-General. Jean, a multilingual, Haitian-born filmmaker and journalist, offered a forward-looking address that stressed, as had Vanier's, the importance of mutual tolerance for Canada's social well-being. Otherwise, however, there were no themes in common, for Jean's primary concern supporting individual liberty; for her, Canadian history "speaks powerfully about the freedom to invent a new world." In this speech there was no mention of the deity. [58]

Benchmarks in the evolution of religious freedom and equality rights in Canadian case law since the 1960s include adopting and applying “reasonable accommodation” approaches to creed and freedom of religion cases under the Code and Charter in the 1970s. This supported the right to not only non-interference or freedom from religious coercion, but also a positive right or entitlement to have one’s religion/creed beliefs and practices accommodated to the point of undue hardship.[59]

Legal scholars note a further evolution of creed rights in recent years. “Adverse-effect” discrimination claims have increasingly challenged systemic forms of discrimination and the way “things have always been done.” For example, (Bhabha, 2012) argues that the new “transformative vision of religious freedom” is about more than seeking exceptions to rules and norms in public space (as accommodation has traditionally been conceived). It is also about engaging to redefine and reconstruct public space itself.[60] Despite such significant advances, various forms of discrimination continue in today’s more secular world. The next section explores some of these.

[31] Periodisation based on Seljak (2012); see also; Beyer (2006); Beyer (2008); Bramadat (2005); and Grant, (1988) for similar periodisations.

[32] The main forms of religious diversity among early settlers in Canada overwhelmingly involved variations of Christianity. The popular hold of Roman Catholicism in Quebec, along with growing Christian religious diversity with the immigration of Lutherans, German Reformed Christians, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Mennonites, Eastern Orthodox, and Irish Roman Catholics over the course of the late 18th and 19th century, scholars argue, led the early governors of Canada and Ontario to adopt a more strategic and pragmatic approach, in part an effort to deter and dissuade dissent and rebellion. Statistical data on religion since the late 1800s also reveals that Sikhs, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, even if not always counted, have also all been present in Canadian society at least since the first census (Beaman & Byer, 2007; Beyer, 2008; see also Bromberg, 2012). Some argue that this pluralism not only forced the early recognition of religious freedoms, but also played a key role in evolving democratic institutions in Canada more generally (see Seljak et al., 2008).

[33] The Supreme Court of Canada traces the first expression of religious freedom in Canada to the 1760s, more specifically the (1763) Treaty of Paris, which, while bringing New France under the control of the British Crown (and by default, the Anglican Church of England), simultaneously “grant[ed] the liberty of the Catholick [sic] religion to the inhabitants of Canada” (Saumur v. City of Quebec and Attorney General, [1953] 2 S.C.R. 299 at 357, cited in Bhabha, 2012).

[34] For more on the idea of “plural establishment,” see, Novak (2006), O’Toole (2006), and Seljak (2007).

[35] David Martin describes these officially recognized churches as functioning as a “shadow establishment” in the century of “Christian Canada” that followed Confederation. The term denotes the “semblance of detachment that the church maintained from the affairs of the state, when in reality, ’separation’ really was mostly a demarcation of responsibilities” (Bramadat et al., 2008). The mainline Christian churches provided the new nation with its most sacred symbols and narratives, guiding its moral vision and cultural orientation. These churches also:

- semi-autonomously ran various public institutions in the new dominion, including education, healthcare and social services

- helped to legislate Christian morality (for example, passing laws protecting the Lord’s Day, imposing restrictions on divorce, marriage, sexual morality, abortion, the sale and consumption of alcohol etc.)

- greatly influenced public policy and culture, partly from the pulpit (Canada had one of the highest church attendance rates in the world from the mid-1800s until the 1960s) (Seljak et al., 2007; Seljak et al., 2008).

[36]Also see Seljak et al. (2007); Seljak (2012).

[37] Biles and Ibrahim, 2005, p. 162 define social capital as “the community resources – the networks of social relations and the culture they generate – to achieve a common goal”. Scholars further distinguish between bridging capital which “connects individuals across community lines” and bonding capital which “strengthens ties within groups” (Kunz, 2009, p. 12; see also Benson (2012b); Buckingham (2012); Jedwab (2008).

[38] This estimate comes from the Canadian Non-profit and Voluntary Sector in Comparative Perspective, which reports on the sector in 37 countries based on size, scope and donations. Among the registered religious charities (in Canada), more than 40% (32,000) are faith-based, which includes places of worship, clubs and other forms of association. (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2009; citing Hall et al., 2005).

[39] Seljak, 2012, p. 9. According to this “commonsense,” Peter Beyer, 2008, p. 14 further explains:

There were the white, European, Christian and civilized peoples, some of who were admittedly ‘more equal than others’; then there were the unalterable ‘others’ who had to be kept apart or, to the extent deemed possible, ‘civilized’.

[40] Summarizing the key impact and intent of the Indian Act of 1876, Beyer, 2008, p. 14 notes:

By the end of the 19th century, Canadian governments were pursuing a concerted policy whose aim was to assimilate Aboriginal people completely, to dissolve their separate identities both culturally and religiously. The Indian Act of 1876 was the corner stone and provided the blueprint for this policy. It effectively made Aboriginal people wards of the state, proscribed their religious practices, suppressed their distinct and highly varied forms of social and political organization, and attempted to socialize their children in residential schools run by Christian churches and designed to eliminate all distinct aboriginal cultural features, including language.

[41] See the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) history of residential schools in their 2012 publication, They Came for the Children available on the TRC website at www.trc.ca. In a section exploring the role of the churches, this publication explains:

Nineteenth-century missionaries believed their efforts to convert Aboriginal people to Christinaity were part of a worldwide struggle for the salvation of souls…The two most prominent missionary organizations involved with residential schools in Canada in the nineteenth century were the Roman Catholic Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Church Missionary Society of the Church of England (the Anglican Church)…Methodist and Presbyterian mission societies, based in both Great Britain and the United States, also carried out work in Canada in the nineteenth century, and became involved in the operation of the residential school system…In his 1889 book The Indians: Their Manner and Customs, Methodist missionary John Maclean wrote that while the Canadian government wanted missionaries to “teach the Indians first to work and then to pray,” the missionaries believed that their role was to “Christianize first and then civilize” (2012, pp.13-14).

[42] The term “antisemitic” is used here, as opposed to the alternate spelling of “anti-Semitic”, for reasons explained in a formative (2002-2003) European Union Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC) Report:

The notation “antisemitism” will be given preference to the notation “anti-Semitism”. This allows for the fact that there has been a change from a racist to a culturalist antisemitism, and in this context

helps to avoid the problem of reifying (and thus affirming) the existence of races in general and a “Semitic race” in particular (p.11).

While the term anti-Semitism, in this view, reproduces the false notion of the existence of a “Semitic” race, and, as such, more strictly connotes racist forms of anti-Jewish thinking and behaviour, the term “antisemitism” can encompass new forms of hostility towards Jews or Judaeophobia that may not depend on notions of Jewish people as a “race” (see Section III 3.2.4 for further exploration of evolving forms of antisemitism historically and in the present).

[43] Bromberg, 2012, p. 61. Bromberg goes on to note how “[i]n 1829, the law requiring the oath ‘on my faith as a Christian’ was changed to allow Jews to not take the oath”. “In 1831,” she moreover notes, “a law which granted full equivalent political rights to Jews was passed, a first for the British Empire” (ibid.).

[44] Employment discrimination against Jews was common well into the 50s and 60s. Many institutions had quotas on the number of Jews they would hire, or forbidding their employment altogether (such as the City of Toronto’s police force). In workplaces, and in both public and private facilities, signs commonly stated, “Gentiles Only,” or “No Jews or Dogs Allowed.” Overt discrimination was also happening in education, the military and in housing. For example, it was common for neighbourhood organizations and land developers to band together to form agreements (“racial restrictive covenants”) to not rent or sell housing to members of unwanted races (including Jews), and/or to place such clauses in property deeds to maintain segregated neighbourhoods. Animosity towards Jews was particularly pronounced during economic downturns, such as the Depression of the 1920s and 30s, during which “foreigners” of various kinds were scapegoated. This included Canadian-born Jews, and often drew on rising international antisemitic propaganda, exemplifying the impact of globalization trends before the current era. See Adelman and Simpson (1996); Davies (1992); and Mock (2008).

[45] Liberal Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King (Canada’s longest-serving Prime Minister) voiced such beliefs in Jewish inferiority, reflecting acceptable norms at the time. A 1943 Gallup poll, for instance, put Jews in third place, below the Japanese and Germans, as the most undesirable immigrants to Canada (Adelman & Simpson, 1996).

[46] See Bromberg (2012) and Patrias and Frager (2001) for more on the key historical role of Jewish Canadians in passing the Ontario Human Rights Code and other anti-discrimination legislation.

[47] The Act required all Chinese immigrants entering Canada to pay a $50 fee, which became known as a head tax. By 1903, the fee had increased to $500. This served, in effect, as a strong deterrent to further Chinese immigration after Chinese labourers built the Canadian Pacific Railway in the late 19th century. While the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act removed the head tax, this Act also stopped all Chinese immigration with few exceptions (such as business people, clergy, educators and students).

[48] This Act prohibited the immigration of persons who “in the opinion of the Minister of the Interior" did not "come from the country of their birth or citizenship by a continuous journey and or through tickets purchased before leaving their country of their birth or nationality.” This, in effect, barred immigration from South Asia since the long journey by boat necessitated a stopover in Japan or Hawaii to refuel and resupply.

[49] See, for instance, Lai, Paper and Paper (2005). Peter Beyer (2008) describes popular and government reactions to the significant growth and ethnic and religious diversification of Canada’s population between 1881 and 1911 as follows:

The dominant Canadian identities could with some reluctance and suspicion accommodate the presence of Russian Doukhobors and eastern European Jews, but not Japanese Buddhists, Chinese Confucians, or Punjabi Sikhs…From the time of the first Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 to the second of 1923, government policy progressively made it more difficult and then virtually impossible for people from above all India, China, and Japan to enter Canada. The dominant attitude was that such people were just too unalterably foreign even to be assimilated (p. 13).

[50] The information about this case is derived from an article by Kevin Plummer, “Historicist: Citizenship and Character,” published in the online journal, Torontoist, on July 16, 2011. Drawing on archival material from, among other sources, an April 3, 1965 Toronto Star article, Plummer relates reported testimony from the original Citizenship proceeding as follows:

[Judge] Leach asked what church they attended. “None,” Ernest replied. Didn’t the Bergsmas believe in God, the dumbfounded judge asked. Ernest paused to consider his answer and then replied, “No.” “Do you know that this is a Christian country?” Leach replied, according to a court transcript quoted in the press. “You must believe in something. The oath (of allegiance) doesn’t mean anything if you don’t believe in God…The things we believe in, in this country, stand for Christian values and the teachings of Jesus Christ.” He added: “Not everybody follows this, but that is what we try to attain in this country, the Christian way of life. I feel you must have some kind of faith, but you don’t seem to believe in anything from what I can gather… As I understand from your evidence, you have no religion at all.”

In the first appeal ruling at the Supreme Court of Ontario on March 17, 1965, Justice Stanley Nelson Schatz upheld this decision.

[51] The oath of allegiance which was required by law of all new citizens read: “I — swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, her Heirs and Successors, according to the law, and that I will faithfully observe the laws of Canada and fulfill my duties as a Canadian citizen so help me God” (Cited in Plummer, 2011).

[52] See Bussey (2012) for poignant example of discrimination against Seventh Day Adventist conscientious objectors during WWII. The persecution, and advocacy efforts, of Jehovah’s Witnesses played a particular key role in advancing freedom of religion laws in Canada (see for instance Bhabha, 2012 for an account of precedent-setting case law in this respect).

[53] Seljak, 2012, p. 9 for instance notes that much of the anti-Catholicism in Protestant Canada before the 1960s was connected to prejudice against French Canadians (the great majority of whom were Catholic), as well as “anti-immigrant sentiment aimed at the Irish, Italians, Germans and other newcomers from Eastern and Southern Europe”. Dominant “White” racial identities of the time were far from inclusive of all European ethnic groups. Canada and Its Provinces (1914-17), a popular and respected history text published in Toronto in 1914, presents Galatians as mentally slow; Italians as devoid of shame; Turks, Armenians, and Syrians as undesirable; Greeks, Macedonians and Bulgarians as liars; Chinese as addicted to opium and gambling; and the arrival of Jews and Negroes as ”entirely unsolicited” (Mclaren, 1990).

[54] Scholars vary in how they explain these transformations in Canadian policy, law and sensibilities. Most acknowledge multiple causal factors at work. These include:

- unintended impacts of state centralization and expansion during WWII, which accelerated secularization processes (differentiation, rationalization of spheres, etc.);

- growing human rights awareness and community activism, mainly in response to the genocidal atrocities committed by Nazi Germany during WWII, but also as inspired by the US Black civil rights and strengthening labour movement;

- to a lesser degree, the growth of diversity in Canada following immigration policy reforms in the late 1960s (see Appendix I charting historical legal, policy and demographic shifts over this era).

The steady increase in the number and kind of ethno-cultural and religious categories reported in Canadian censuses over the last century – ethnic categories jumped from 30 to 232 from 1911 – 2001, and religious categories from 32 to 124 – are just one indication of this demographic transformation (Byer, 2008).

[55] There has been a move away from overt policies of assimilation requiring people to abandon cultural and religious differences to gain equal citizenship. The introduction of policies and legislation protecting minority groups’ ’right to be and remain different’, Seljek et al. argue (2008), reflects a significant transformation from a politics of social hierarchy emphasizing and privileging the rights of political, economic and social elites, towards what Charles Taylor calls a ’politics of universalism’: a new consensus based on ideals of equality and non-discrimination.

This new universalism can be seen in the introduction of anti-discrimination legislation in the inter-war years, and its consolidation after that. Examples are:

- the Ontario Human Rights Code enacted in 1962, after the Bill of Rights first introduced human rights law at the federal level in 1960;

- the lifting of some of the more draconian restrictions on Aboriginal cultural and religious practices in the 1950s and 1960s (granting Aboriginal people with “Indian status” full Canadian citizenship and the right to vote in 1960);

- the introduction of non-discriminatory federal immigration policy in the 1960s, and the state policy of multiculturalism in 1971 (later enacted in 1988), in the context of a greatly diversified and expanded (non-English and French) immigrant population;

- perhaps most significantly, the enshrinement of individual and minority group rights, multiculturalism and religious freedom in the repatriated 1982 Constitution Act’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[56] Signs of this growing separation of church and state, erosion of Christian privilege, and decline of its power to define public morality, post-1960, include:

- liberalizing laws governing sexual morality, marriage, divorce and abortion, beginning with the Trudeau governments (1968-1979, 1980-1984);

- displacing church control and assuming state control over healthcare and social services since the 1960s;

- de-Christianizing Canada’s public schools, especially after the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and increasing public questioning of special government funding of Roman Catholic separate schools in Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan;

- overturning the Lord’s Day Act (1906) in 1985 to allow Sunday shopping;

- a series of cases since then, that seek to put religions on an equal footing in the workplace (Bramadat et al., 2008; Seljak et al., 2007).

[57] Summing up such transformative developments, Seljak,et al. (2008) observe: “Christianity no longer enjoys the public power and prestige it once had. Christian churches no longer control the powerful social institutions they once operated hand-in-glove with the various levels of government. To a significant extent, religion in Canada has been privatized.”

[58] Seljak, D., Schmidt, A. & Steward, A. (2008). Secularization and the Separation of Church and State in Canada. Multiculturalism Report # 22 (Unpublished)

[59] There were several key Supreme Court of Canada legal decisions in the 1950s that extended protection from discrimination to various disfavoured religious minorities, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, long before the Charter enshrined religious freedom and equality (see Bhabha, 2012 for details on some of the cases). Bhaba argues that human rights tribunals largely followed American civil rights jurisprudence when they incorporated “reasonable accommodation” approaches to resolving workplace disputes in the 1970s. (Ibid.). Bhaba states that this approach was first applied to freedom of religion cases under section 2(a) of the Charter in the seminal R. v. Big M Drug Mart Ltd. case in 1985 ([1985] 1 S.C.R. 295).

[60] Bhabha (2012) cites the recent issue of Muslim congregational prayers in a Toronto-area middle-school cafeteria as one recent example of this new “transformative” versus merely “accommodative” vision of religious freedom. The section below on creed accommodation further traces the legal evolution of this more transformative and systemic approach.

3. Current discrimination trends

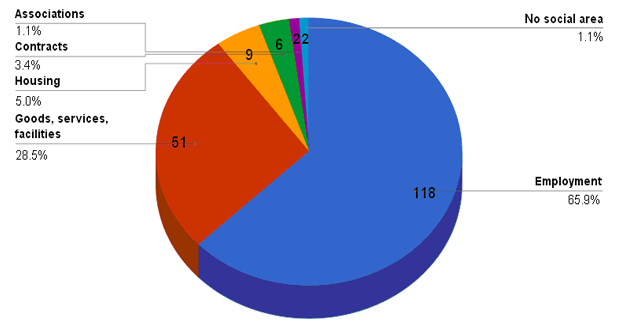

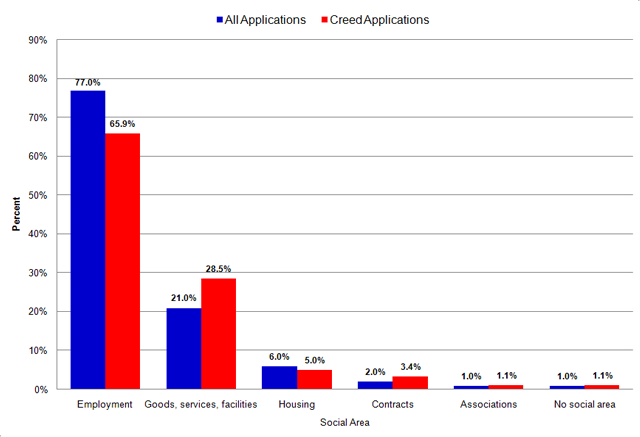

3.1 Profile of HRTO creed applications (2010-2012)

The OHRC reviewed all applications (formerly known as “complaints”) filed with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO) citing creed as a ground of discrimination in the 2010-11 fiscal year (April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011), and 2011-12 fiscal year (April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2012). We started with a list of applications that the HRTO collated from its case management database, and ended up including 179 applications for review in 2010-11, and 140 for review in 2011-12.[61]

Applications citing creed accounted for 6.8% of all HRTO applications filed in the 2011-12 fiscal year, up slightly from 6% in 2010-11 (see the Chart below and Appendix 22.1 for breakdown of HRTO applications filed in the 2011-12 and 2010-11 fiscal years by ground). While this number appears relatively low, it may not reflect the actual extent of discrimination experienced by various communities in Ontario, due to such factors as under-reporting, mis-reporting, and the unknown outcome of applications alleging discrimination.[62] HRTO application statistics reported on here provide a description of the number and nature of applications citing creed as a ground of discrimination filed at the HRTO. It is difficult to gauge how much this may reflect broader trends, in part for the above-mentioned factors.

2011-2012 HRTO applications by ground

|

Ground |

Totals* |

|

Disability |

54.4% |

|

Reprisal |

25.5% |

|

Sex, pregnancy and gender identity |

24.9% |

|

Race |

29.2% |

|

Colour |

13.5% |

|

Age |

13.6% |

|

Ethnic origin |

15.5% |

|

Place of origin |

12.6% |

|

Family status |

8.4% |

|

Ancestry |

9.1% |

|

Sexual solicitation or advances |

5.2% |

|

Creed |

6.8% |

|

Marital status |

7.8% |

|

Sexual orientation |

4.0% |

|

Association |

2.6% |

|

Citizenship |

3.7% |

|

Record of offences |

3.0% |

|

Receipt of public assistance |

1.0% |

|

No grounds |

2.6% |

Source: HRTO, retrieved June 21, 2013, from www.hrto.ca/hrto/?q=en/node/152

*The above chart shows the percentage of applications in which each prohibited ground under the Code is raised. Because many applications claim discrimination based on more than one ground, the totals in the chart far exceed the total number of applications received.

3.1.2 Applications by creed affiliation

In both the 2010-11 and 2011-12 fiscal years, Muslims accounted for the highest number of HRTO applications citing creed as a ground of discrimination, closely followed by Christians (of all denominations). According to the 2011 National Household Survey, Muslims made up 4.6% of Ontario’s population in 2011. Relative to their population size, Muslims were highly over-represented among HRTO applicants, accounting for more than one-third (36%) of all HRTO creed applications in 2011-12 and 31.8% in 2010-11 (see Appendix 22.2 and 22.5 for further details). This finding is consistent with research on the growth of Islamophobia and other discriminatory trends affecting Muslim communities, particularly following 9/11, as noted in Section 3.2.5 below. The review of HRTO applications, moreover, revealed that Muslims were not the only target of such trends. Several applications involved claims of discrimination by non-Muslims who alleged they were targeted because they were wrongly perceived to be Muslim. [63] This may show that race is a factor in anti-Muslim discrimination, when victims are discriminated against because of their outward appearance, rather than their actual beliefs (as discussed in Sections 3.2.3 and 3.2.5 below).

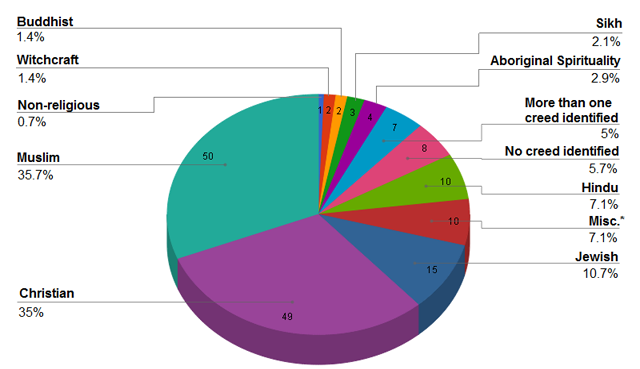

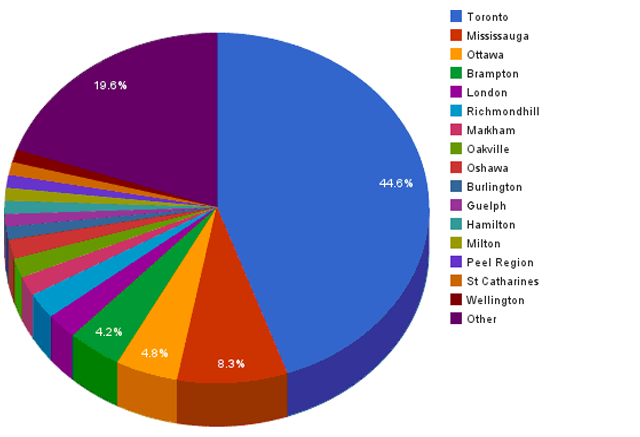

Number and percentage of HRTO applications citing creed by creed affiliation (2011-2012 fiscal year)

*Miscellaneous: Elemental magic, Ethical veganism, Kabala, Membership in law society of Canada, Rastafarian, Taoism, Wiccan, Yoga system & cosmology, Zen, Zoroastrianism

While Christians overall are not over-represented among applicant groups relative to their population size,[64] they are involved in a significant number of HRTO cases, lending some credence to the perception that Christians may also feel like “minorities” at times in Ontario’s increasingly secular society (in some cases, despite being a majority). Among creed groups, Christians (of all denominations) [65] accounted for the second highest number of HRTO applications citing creed as a ground of discrimination, in both the 2010-11 and 2011-12 fiscal years. Some 35% of HRTO creed-based applications filed in 2011-12, and 26.8% filed in 2010-11, were from persons identifying with various Christian denominations (see Appendices 22.2, 22.3, 22.5, and 22.6 for further breakdown of applications by creed affiliation). Applicants self-identifying as “Roman Catholic” (9.3%) and simply “Christian” (9.3%) made up the largest number of Christian applicants in the 2011-12 fiscal year, followed by those identifying as Seventh Day Adventist (5.7%) and Christian Orthodox (2.9%) (see Appendix 22.3 for 2011-2012 breakdown of creed applications by Christian denominational affiliation). A similar pattern was evident in HRTO creed-based applications in the 2010-11 fiscal year (see Appendix 22.6).

Relative to their population size,[66] members of the Jewish (15 or 10.7%), Hindu (10 or 7.1%), Traditional Aboriginal (4 or 2.9%) and Sikh (3 or 2.1%) faiths accounted for a disproportionate number of 2011-2012 HRTO creed applications, as did a number of lesser known creed groups (e.g. Rastafarians, Raelians, and others grouped as “miscellaneous” in the graphs reporting on 2010-11 and 2011-12 HRTO creed applications; see Appendices 22.2 and 22.5 for for further details). People identifying as non-religious – whether atheist, agnostic or simply non-religious – accounted for a relatively small number (2 or 1.4%) of HRTO creed applications in 2011-12, but a larger portion (some 5%) in 2010-2011. In both fiscal years, a significant number of applicants did not identify with any particular creed (19 or 10.6% of creed applications in 2010-11 and 8 or 5.7% of creed applications in 2011-12).

The earlier discussed trend of increasing individualism, hybridity, and eclecticism in patterns of contemporary creed belief and practice was in part evident in the significant number of HRTO creed applications – some 5% or 7 in 2011-12 – in which the applicant identified with more than one creed (see Section 1.2 above and Appendix 22.4). There was also an observed tendency among some some applicants, particularly in 2011-12, to elevate what may appear to be more isolated opinions and beliefs to the level of a creed (e.g. belief in “being truthful”, “good business practice”, “fairness”, “respect and dignity for hard work” etc.) (see Appendix 22.5).

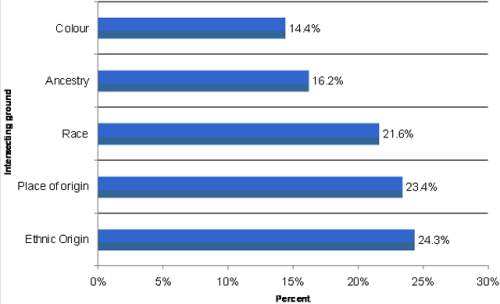

Intersecting grounds

Percentage of HRTO applications citing creed by intersecting grounds (2011-2012 fiscal year)