Appendices

Appendicies

Appendix 1 - Recommendations

The OHRC’s recommendations consist of actions the TPS and TPSB must take to:

- address systemic racial discrimination, racial profiling, and anti-Black racism

- be held accountable for their implementation, and

- improve outcomes for Black communities.

The recommendations are informed by OHRC’s findings through the course of our Inquiry. They are based on research and consultations with:

- Black communities in the Greater Toronto Area

- subject matter experts

- the TPS, TPSB and TPA

- a roundtable on policing hosted by the OHRC and TPSB

- best practices from jurisdictions across North America, and

- successful evidence-based strategies developed over a span of 30 years of public inquiries, policy and litigation experience related to policing.

Most recommendations are directed to the TPS and the TPSB, and can be acted upon without changes to existing legislation. Some recommendations may require amendments to legislation or changes to longstanding provincewide police practices to achieve the recommendation’s objective. Those recommendations are directed to the province, although they call upon the TPSB to engage with the provincial government to address the areas we have identified at a provincial level.

The OHRC recognizes that since the Inquiry’s launch, the TPSB and TPS have introduced initiatives addressing anti-Black racism and discrimination that are documented in this report. The recommendations address continuing gaps identified through the OHRC’s review of policies, procedures, training, and accountability mechanisms.

Although the OHRC attempted to ensure its recommendations reflect current initiatives, the OHRC acknowledges that since this report was written, the TPS and TPSB may have introduced new initiatives or enhanced existing ones.

Use of experts

For many of the recommendations, it will be clear that TPS and the TPSB will need to utilize various experts to guide them, as they did in developing their race-based data collection practices. In addition to subject matter expertise, such experts should have sensitivity to the issues concerning systemic racism in policing, including anti-Black racism, and where possible, relevant lived experiences.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and TPSB work with experts to:

- Incorporate all the Inquiry’s recommendations into its policies, procedures, training and education, anti-racism initiatives, and accountability mechanisms.

- Identify leading practices and key performance indicators for addressing systemic discrimination and reducing race-based disparities.

- To this end, the expert(s) should work with the TPSB to enhance ongoing efforts to monitor compliance with and the impact of the initiatives that address anti-Black racism.

- Comply with monitoring and accountability mechanisms identified in this report.

- Ensure that strategies adopted to implement this report’s recommendations are thoroughly evaluated on an ongoing basis and facilitate public access to data. Evaluation may include, but not be limited to, internal audits and random compliance testing. These strategies should form part of the action plan identified in Recommendation 3 below.

Engagement

Transformative change in police practices in Toronto must be informed by community views, experiences, and perspectives. This requires meaningful engagement with Black community advisory groups and concerned

members of Black communities more generally. As set out in the report, it is clear that the TPS and TPSB have taken steps to ensure that public consultations are conducted and have the ability to inform the development of their projects.

As such, our recommendations in this area seek to build upon these efforts to help ensure that the development, implementation, and review of police practices are continually informed by voices of Black communities, in a meaningful way at the foundational level.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and TPSB engage Toronto’s diverse communities in creating an action plan to implement all the OHRC’s recommendations. The action plan should also incorporate TPS’s ongoing efforts to address discrimination and anti-Black racism in the Service. This will help ensure that TPS/TPSB’s policies, procedures, training, anti-racism initiatives, and accountability mechanisms are consistently reviewed and enhanced on an ongoing basis. OHRC recommends that this engagement acknowledges and be sensitive to the specific impact police practices have had on the range of lived experiences and intersectional identities that exist in Black communities. Community participation should be drawn from a variety of organizations, panels and groups, including but not limited to the Anti-Racism Advisory Panel’s (ARAP), Police and Community Engagement Review (PACER), and/or the city of Toronto’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism unit (CABR).

- In consultation with Black communities, the TPSB should consider whether this action plan should form part of the strategic plan for the provision of policing, required by s. 39(1) of the Comprehensive Ontario Police Services Act when it comes into force.

- In consultation with Black communities, the TPSB should consider whether this action plan should form part of the strategic plan for the provision of policing, required by s. 39(1) of the Comprehensive Ontario Police Services Act when it comes into force.

- The TPSB expand ARAP’s mandate to include providing ongoing advice on the implementation of the OHRC’s recommendations. The TPSB should develop a process to ensure that advice from ARAP is carefully considered and informs decision-making. In order to assist with these tasks, the TPSB should ensure that ARAP is adequately resourced.

- The TPS and TPSB work with community groups to identify the desired outcomes from the engagement process, and track the extent to which those outcomes have been fulfilled by conducting pre- and post- engagement surveys or adopting other relevant measures.

Chapter 3 – Anti-Black racism in policing in Toronto

Given this report’s finding of systemic anti-Black racism, the TPS and TPSB should issue an official acknowledgement of the findings from the OHRC’s Inquiry – one that is substantive and specific.

Acknowledgement

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and the TPSB acknowledge the findings from the OHRC’s Inquiry and their impact on Black communities and individuals. The OHRC draws upon the recommendations in the Missing and Missed Report1 for the foundational principle that an acknowledgement should only be made if heartfelt and accompanied by a detailed plan for action that is subject to independent monitoring as set out below. The content of the acknowledgement and action plan must be developed in partnership with Black communities.

Chapter 4 – Consultation with Black communities, community agencies, and police

Over the course of the Inquiry, the OHRC held extensive consultations with a wide range of stakeholders. This included engagements with members of Black communities and organizations that serve Black communities in various settings, including interviews, focus groups, and a policy roundtable which created a space for community members and police leaders to discuss pressing issues and potential reforms.

The OHRC also consulted with TPS leadership and TPSB and TPA representatives and conducted a survey of officers (below the rank of inspector). Each of these groups shared their concerns and views on how to address systemic discrimination.

Black Community Renewal Fund

During our conversations with Black people, we heard about the lack of trust between Black communities and the police. Much of the lack of trust stems from the trauma that follows negative interactions with the TPS. We heard strong support for the TPS taking action to address this trauma through tangible restorative measures.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and TPSB establish a renewal fund dedicated to developing or advancing community safety and well-being initiatives for Black communities. This may take the form of allocating annually a portion of the TPSB Special Fund to organizations that serve Black communities.

Reducing the scope of police activities

Community members have consistently advised policymakers that the allocation of public safety resources does not align with community needs. For example, the top three recommendations the TPS received from communities during town hall meetings about police reform in 2020 were “defunding” the police, “de-tasking” police services and investing in mental health and addiction services. Similarly, the OHRC consistently heard concerns that certain community safety issues to which the TPS responds could be addressed more effectively by a non-policing agency.

As aptly stated in Missing and Missed, many want the police to give up some tasks to other public and community agencies with greater expertise, such as dealing with people in mental health crises or working with the unhoused.2 All recommendations made in Missing and Missed, including those addressing these issues, were accepted by the TPS and TPSB.

In response to community-based concerns, and the current discourse on policing that calls for re-imagining the way policing is delivered, the OHRC makes the following recommendations.

The TPS and the TPSB implement strategies to transfer3 certain functions currently being performed by armed police officers to other public and community agencies with better expertise.

The TPS and the TPSB implement strategies to transfer3 certain functions currently being performed by armed police officers to other public and community agencies with better expertise.

- In doing so, the TPS and TPSB work in collaboration with Black community organizations to identify alternative responses for calls that police are currently attending, where such attendance is likely not essential.

- In doing so, the TPS and TPSB work in collaboration with Black community organizations to identify alternative responses for calls that police are currently attending, where such attendance is likely not essential.

- The TPS and the TPSB continue to work with the City of Toronto’s Community Crisis Service (TCCS) and support efforts to expand TCCS services that focus on Black communities.

- The TPS and the TPSB publicly support community calls to expand community-led mental health crisis responses to reduce police interactions with people in crisis.4 Community-led mental health crisis responses should be culturally responsive to diverse communities, including Black communities.

Diversity and racial discrimination in employment

To change the culture of policing, the TPS must reflect the diversity of the communities it serves. People with lived experience of anti-Black racism can help improve internal processes and shift mindsets that have failed to address systemic racial bias in policing.

- The TPS and TPSB develop and conduct periodic workplace censuses on the extent to which Black persons are represented at all levels of the organization. The results of each census should be regularly disclosed to the public.

- The TPS establish key performance indicators, benchmarks, and targets on their employment equity initiatives, and publicly report on these targets to the TPSB annually.

- Criteria for taking decisions about promotions should include, where possible, an officer’s skill and experience with members of Black communities and other racialized communities, and an officer’s experience and demonstrated ability to de-escalate and negotiate during crisis situations and/or scenario-based evaluations. Such scenarios may be informed by the issues identified in this report.

- The TPS and the TPSB regularly consult with the Black Internal Support Network (BISN) about the experiences of Black employees, and their views on TPS’s service to Black communities. Engagement with the BISN should inform TPS initiatives aimed at providing bias-free policing. The TPS and TSPB should consider whether the feedback they receive from the BISN should be shared at a public board meeting. The decision to report on these consultations should be made in consultation with the BISN.

Chapter 5 – Stop and search (non-arrest circumstances)

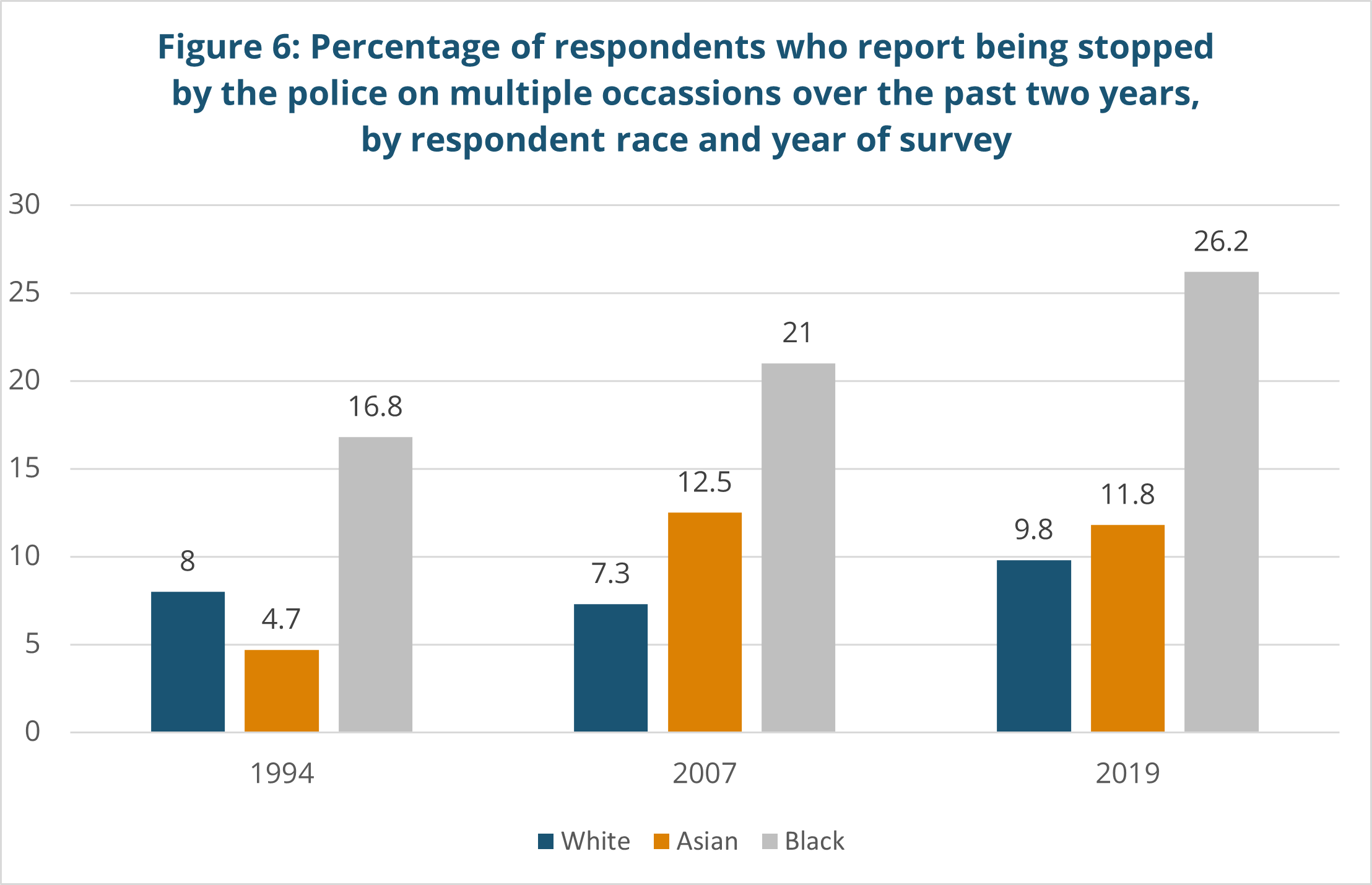

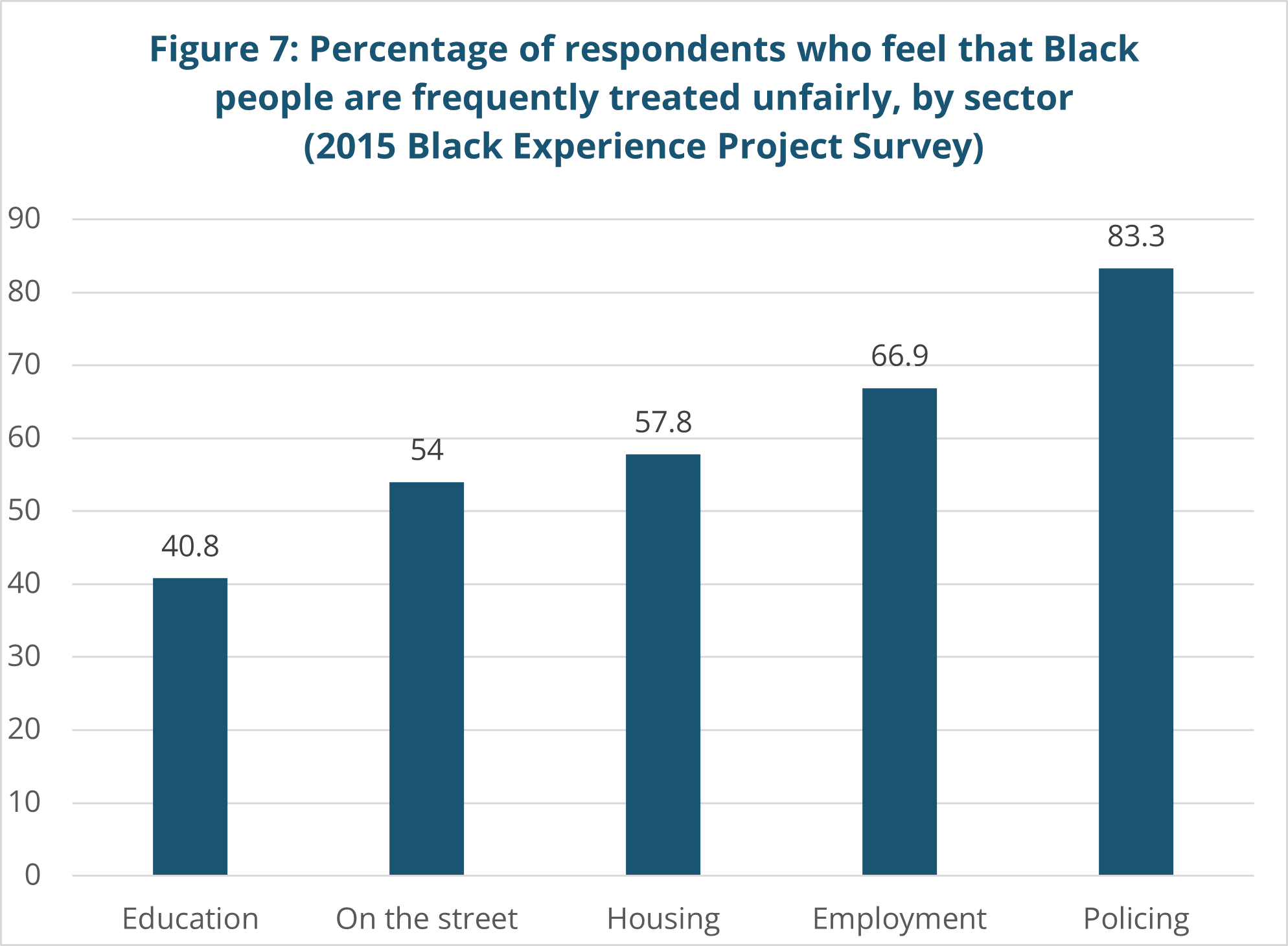

An officer’s authority to approach, stop, or question a civilian has been fiercely contested. The practice of carding provides the foremost example of Black people’s concerns regarding the exercise of discretionary police power to stop and question, and its impact on Black communities.

The OHRC acknowledges initiatives undertaken by the TPS, TPSB, and the provincial government to engage with Black communities and revise practices in this area. This includes O. Reg. 58/16: Collection of identifying information in certain circumstances, which banned arbitrary stops.

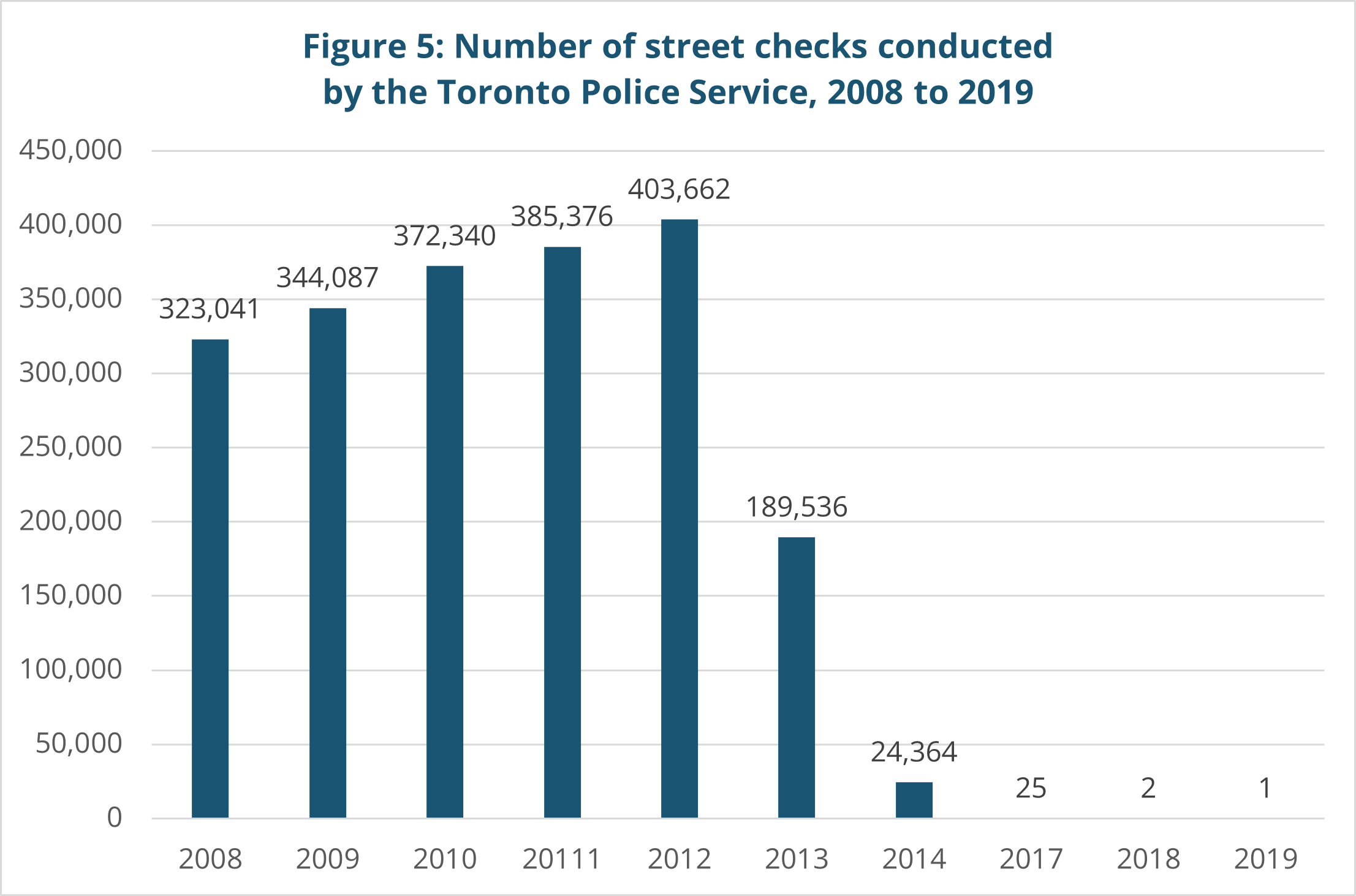

Notwithstanding the existing ban on arbitrary stops, and the decision to monitor annually the number of street checks conducted by the TPS, the OHRC continued to hear significant concerns about unjust stops during our Inquiry. The Inquiry has documented significant gaps in TPS and TPSB policies and procedures regarding stops and searches that help perpetuate systemic racial discrimination.

In response to these concerns, the OHRC recommends the following actions – which go beyond the protection provided by O. Reg. 58/16, and the related policies and procedures.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and TPSB develop and implement criteria that narrow the circumstances where TPS officers can approach or stop a person in a non-arrest scenario, and a framework for rights notification that is consistent with the OHRC’s criteria in its Submissions to the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services as part of its Strategy for a Safer Ontario.5

These criteria are more stringent than the criteria mandated by the Province in Ontario Regulation 58/16, Collection of Identifying Information in Certain Circumstances – Prohibition and Duties.

Search of persons

- The TPS include detailed criteria in its Search of Persons procedure (01-02) for when officers may conduct “safety” searches and “frisk” searches consistent with the Charter and case law.

Chapter 6 – Arrests, charges, and artificial intelligence

In A Disparate Impact, the expert analysis of TPS charge, arrest, and release data found that Black people are grossly overrepresented in discretionary, lower-level charges, and more likely than White people to face low-quality charges with a low probability of conviction. Among the charges examined as part of the Inquiry, the charge rate for Black people was 3.9 times greater than for White people, and 7.1 times greater than the rate for people from other racialized groups.

Despite being charged at a disproportionately higher rate, Black people were overrepresented in cases that resulted in a withdrawal of charges. Black people’s cases were also less likely to result in a conviction compared to cases involving White people.

In Chapter 7, we acknowledge the steps that the TPS has taken to better understand and address anti-Black racism and racial discrimination in charges and arrests. This includes extensive work to collect, analyze and report on data in this area.

In June 2022, the TPS released an analysis of its race-based data on use of force and strip searches. This included data regarding “enforcement actions,” which contains data on charges and arrests. For example, the data shows Black people were 2.2 times more likely to be involved in “enforcement actions,” i.e., “incidents that result in arrests, apprehensions,

diversions, tickets, or cautions for serious provincial offences, and includes those classified as suspects or subjects in occurrence records.”6

The OHRC proposes that the TPS and TPSB address racial disparity in charges and arrests by advancing policies and procedures with respect to charges and other enforcement actions (e.g., police cautions, alternative measures). This proposal is based on the finding that TPS procedures and training do not provide sufficient guidance to officers to determine whether to lay charges, arrest, or use alternatives.

The OHRC has also explored the potential benefits of Crown pre-charge approval. Implementing Crown pre-charge approval would require involvement from the Province. As such it is addressed along with other recommendations to the Province further on.

Laying a charge

The OHRC recommends that:

-

The TPS ensure that its procedures on laying a charge require that officers approach all interactions with Black and other racialized individuals in ways that consider their histories of being over-policed,7 and consider the use of alternatives to charges and arrests, where appropriate. This includes and builds on the officer’s discretion to use informal warnings, cautions, or diversion programs.

- The TPS expand the use of youth and adult pre-charge diversion and restorative justice programs that allow unlawful behaviour to be addressed without formally laying a charge in appropriate circumstances. Where possible, the TPS should make referrals to culturally appropriate diversion programs and monitor the number of referrals they make to these programs.

- The TPS expand the use of youth and adult pre-charge diversion and restorative justice programs that allow unlawful behaviour to be addressed without formally laying a charge in appropriate circumstances. Where possible, the TPS should make referrals to culturally appropriate diversion programs and monitor the number of referrals they make to these programs.

- The TPS regularly review and purge its data base of fingerprints, photographs, and other biometric information collected as a direct result of charges that do not result in convictions, absolute discharges, and satisfied peace bonds.

- TPS procedures:

- Require that the TPS conduct equity audits of charges laid for the following provincial offences, and administration of justice charges at the unit level. These audits should monitor whether Black persons are overrepresented in:

- Trespassing

- Out-of-sight driving offenses (including driving without a valid licence, driving without valid insurance, driving while suspended, etc.)

- Failure to comply with a condition, undertaking or recognizance.

- Should take appropriate action to address any disparities identified.

- The TPSB incorporate Recommendations 16, 17 and 18 into its anti- racism initiatives and accountability mechanisms related to laying a charge.

- Require that the TPS conduct equity audits of charges laid for the following provincial offences, and administration of justice charges at the unit level. These audits should monitor whether Black persons are overrepresented in:

Artificial intelligence (AI)

The TPSB released a Policy on Use of Artificial Intelligence Technologies, which seeks to ensure that use of AI technologies by the TPS does not disproportionately impact Black and other marginalized communities. It is important that the TPS does not use AI technologies in ways that lead to racial discrimination.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB implement the actions set out in the OHRC’s Submission on Ontario’s Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI) Framework,8 and more specifically, the OHRC’s Submission on TPSB Use of Artificial Intelligence Technologies Policy.9

- Until privacy and human rights assessments are conducted, and an expert in technological/algorithmic racial bias is consulted along with the Information and Privacy Commissioner and the OHRC, the TPS should limit the use of AI technologies.

- The TPS publish detailed lists of all data inputs used for place-based predictive algorithms, or for any functionally equivalent AI technology.10

- Ensure that facial recognition software is not used when officers stop, detain or arrest individuals.11

- Ensure that officers are aware of the potential racial bias that may flow from the use of AI tools, and the impact of AI on officer deployment decisions.12 In addition, officers must be capable of implementing strategies to eliminate potential bias which may flow from the use of artificial intelligence tools.

Chapter 7 – Use of force

Police use of force against Black people is among the most controversial issues facing law enforcement across North America. Incidents where police use excessive force undermine confidence in policing and could result in an unjustified death.

Given the critical importance of this issue, the TPS and TPSB must ensure that their policies, practices, training, and review mechanisms require that TPS officers only use force as a last resort, and that any unreasonable use of force is identified and addressed with strong accountability measures. Also, the TPS and TPSB must ensure that officers use de-escalation and non-force techniques to effect compliance with police orders whenever feasible.

The OHRC recommends that:

Use of force

- The TPS and the TPSB publicly commit to a “zero harm, zero death” approach in all interactions with civilians, in particular with Black persons and persons in crisis. The OHRC recommends that the TPSB and TPS publicly report annually on how they are satisfying their commitment, including through public reporting of disaggregated race- based statistics.13

- The TPS and TPSB explore using crisis workers other than nurses as part of the mobile crisis intervention team (MCIT) to provide 24/7 coverage when nurses are not available.14

Use of lethal and less lethal force

Fatal encounters between civilians and the police may undermine public confidence in police services and have a traumatic impact on individuals, families, and communities. As documented in this report, Black people are disproportionately impacted by TPS use-of-force practices, including lethal force. Black people are more likely to be fatally shot by the TPS.

The OHRC has acknowledged the important steps the TPS has taken to address use of force, including an updated Incident Response (Use of Force/De-Escalation) policy, and use-of-force data collection and related action plans referred to in the body of this report.

The OHRC recommends that:

- In keeping with the “zero harm, zero death” objective, the TPS must make every effort to avoid fatal encounters. To this end the limits placed on the discretion to use of force found in the Criminal Code, or training exercises should be reflected in TPSB policies and TPS procedures in order to promote consistency and intelligibility.

- The TPS clarify the requirement to disengage found in the TPSB’s De- escalation and Appropriate Use of Force policy and the TPS Incident Response (Use of Force/De-Escalation) procedure. The policy and procedure should state that disengagement includes taking the necessary time and repositioning where appropriate and safe to do so, to avoid using force.

- In response to the over-representation of Black communities in police shootings and other lethal encounters with TPS documented in this Inquiry, TPS should:

- Continue to closely monitor and report on these disparities and take immediate steps to develop action plans to reduce them.

- Report on the effectiveness of de-escalation efforts when engaged with Black communities.

- The TPS expand circumstances where officers should not use deadly force or shoot to include:

- to prevent property damage or loss, to prevent the destruction of evidence, or against a person who poses a threat only to themselves and not to others.

Duty to intervene

The duty to intervene is a duty to stop other officers from using excessive force or engaging in prohibited conduct. The OHRC welcomes the TPSB’s decision to implement a duty to intervene on all TPS members who observe an officer using prohibited or excessive force, or engaging in acts that constitute misconduct. As a best practice, this duty should be monitored and improved in response to the feedback provided by officers who have intervened.

As such, the OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the duty to intervene and assess whether changes to policy or procedure are required. The monitoring should include collecting data on the number of times officers report that they have intervened and the circumstances that warranted intervention. The aggregate number of interventions should be reported to the TPSB.

Use-of-force reporting

The definitions of “use of force” that warrant reporting are too narrow, and do not reflect the realities of modern policing. For example, the OHRC’s expert analysis has made important findings regarding the disparate impact of lower-level use of force on Black communities. However, lower-level use of force falls outside the scope of incidents that must be reported.

A definition that only considers use of force resulting in injury or hospitalization does not account for the mental health impact and trauma that police use of force has on communities.

The OHRC recommends that:

- Use-of-force reporting be guided by a comprehensive definition of use of force that includes lower-level use of force.16 Use of force that falls within the scope of this definition should be reported to a supervisor and should be included as a new category in the TPS’s ongoing reporting on use of force.

- Use-of-force reporting include the application of handcuffs or mechanical restraints, when they are used to gain compliance from an adult, outside of an arrest. All circumstances where handcuffs or mechanical restraints are used on persons under 18 should be reported.

- Use-of-force reports capture contextual information, such as:

- whether the subject had or was perceived to have a mental health disability, whether the subject was perceived to be experiencing a mental health crisis, or was experiencing issues related to substance abuse

- whether efforts to de-escalate the incident before and after force were applied

- other contextual information relevant to the use of force.

- The TPS take into account the critical issue of potential racial bias or profiling in its use-of-force analysis, and this information be reported in the Race-Based Data Collection report. For each incident of use of force, the TPS should provide the Training Analyst with documents that contain race-based data and a summary of the circumstances that led to the use of force.

- The analysis and identification of trends from the annual use-of-force report be conducted in a manner that is consistent with the objectives of the Human Rights Code and the provincial Data Standards for the Identification and Monitoring of Systemic Racism.

Conducted energy weapons (CEWs)

Discharging a CEW should be subjected to the same investigative standards as a firearm, as use of these weapons is potentially lethal and Code- protected groups remain disproportionately subjected to their use.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS require an investigation into the circumstances that resulted in the discharge of a CEW, as is required under TPS Service Firearms procedure (15-03) for the discharge of firearms.

Use of force and youth

TPS procedures and TPSB policies should provide further guidance for circumstances where an officer engages a young person and considers using force.

The OHRC recommends that:

- Officers, where possible, use de-escalation techniques that are tailored and appropriate when engaged with young persons.17

- Officers seek intervention from trained mental health or child and youth professionals to address non-criminal behaviours exhibited by young persons. This is particularly important for children under age 12.

Chapter 8 – Anti-racism policies, training and evaluation

Policy on eliminating racial discrimination

The OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement contains recommendations to address systemic anti-Black racism in policing that are relevant to the TPS. For example, the TPS and TPSB do not have a distinct policy or procedure on racial profiling. The failure to create adequate policy and procedure to prevent discrimination can contribute to racial disparities and undermine community trust in police.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB enact a policy and direct the Chief of Police to enact a procedure on racial profiling. The policy and procedure should reflect best practices and be consistent with recommendations 15 and 27–34 in the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement.

- The TPSB and TPS regularly assess proactive deployment patterns for concerns about racial profiling, consistent with section 4.2.1 of the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement, and that the TPSB Policy on Community Patrols be amended to include regular assessments of proactive patrol patterns.18

Training and education

The OHRC’s Inquiry found that the TPS and TPSB have committed to study and deliver training and education on racial profiling and racial discrimination. Significant steps have been taken to create useful training on racial bias, racial profiling, and racial discrimination.

Despite these steps, there continue to be gaps in TPS training and education on anti-Black racism, racial profiling, and racial discrimination that should be addressed. They include components that should form part of a TPSB policy and a TPS procedure on racial profiling.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS ensure that new recruits, current officers, investigators, and supervisors continue to receive detailed, scenario-based, human rights-focused training and education.19

- Training be consistent with recommendations 48 to 50 in the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement, and include content from the recommendations of the coroner’s inquests into the deaths of Reyal Jardine-Douglas, Sylvia Klibingaitis, Michael Eligon, and of Jermaine Carby.20,21

Training and education development

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS ensure that officer training and education:22

- Includes scenario-based learning modules to facilitate identifying racial profiling and racial discrimination in investigations, including scenarios dealing with suspect selection, detention, searches, charges, arrests, use of force, and conflict de- escalation.

- Is connected to policies and procedures on racial profiling and racial discrimination, and specifically identifies and counters anti- Black racism in stops, questioning and searches, charges and arrests, and use of force.

- Incorporates concepts, principles, and tools from the TPS’s human rights and anti-Black racism specific training into dynamic simulations on stops, questioning and searches, charges and arrests, and use of force.23

- The TPS include active and ongoing consultation with Black and other racialized communities in its development and implementation of training and educationIncluding in areas that have a disproportionate impact on Black communities, such as charges and arrest, and use of force.

- The TPS develop and implement ongoing, detailed and scenario-based human rights-focused training to new recruits, current officers, investigators, and supervisors on how to mitigate the use of charges as outlined in A Disparate Impact. 24

- Training should include alternatives to charges, such as issuing informal warnings, cautions or diversion, and that training inform officers how to approach all interactions with Indigenous, Black, and other racialized persons in a way that considers their histories of being over-policed, and using alternatives to charges and arrests, where appropriate.

Officer certification and program evaluation

The OHRC recommends that:

- The evaluation of officers’ performance in each component of training includes a benchmark to pass and remedial measures be established for officers who do not pass.25

- Officers be required to obtain certification in de-escalation as they are required to do for firearms and CEWs. Officers who cannot effectively de-escalate incidents should not be allowed to carry firearms.

- Training be evaluated for effectiveness in achieving the objectives, including systemic outcomes, such as reducing racial disparities or reducing implicit bias.26 The evaluation should include outcome measures pertaining to disparity reductions (or a lack thereof) in stops, questioning, searches, charges and arrests, use of force, and other police practices. The OHRC recommends that the TPS publicly report on the results of the evaluations.

Peer intervention

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of their peer intervention program. The monitoring process should include feedback from officers who have been involved with incidents where the duty to intervene was engaged.

Chapter 9 – Accountability and monitoring mechanisms

Legal enforceability

Based on the Inquiry’s findings, the OHRC has concluded that to ensure real change, the TPS and TPSB must commit to specific, systemic, and concrete actions that are legally enforceable. The decades of reports and calls for action from Black communities show that if the TPSB and TPS are committed to change, they must legally bind themselves to that change.

The OHRC has proposed legally binding and enforceable remedies as an accountability measure that will encourage the TPS and TPSB to work with the OHRC and the community to implement the recommendations that flow from this Inquiry.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS and TPSB formally commit to legally binding enforcement measures that are effective, expeditious, and to the fullest extent possible, non-adversarial. The TPS and TPSB should adopt an approach for implementation of the OHRC’s recommendations in this report, developed in consultation with the OHRC and Black communities. Such an approach should be informed by the animating and guiding principles of:

- Promoting timely and effective implementation of the OHRC’s recommendations.

- Continuing Community Engagement and Involvement. This approach will continue to reflect the commitment of the TPS, TPSB and OHRC to robust community engagement and involvement. The TPS, the TPSB and any panels or tables would approach their work in a way that is consistent with that commitment.

- Promoting and Supporting TBPS’s Oversight Capacity. This approach is premised on building TPBS’s capacity to ensure effective oversight and accountability of the Service, including its ongoing evaluation and monitoring of compliance, and providing interim support to the TPSB in supplying that oversight and accountability as its capacity is built up.

- Ensuring that the composition of any panels, tables or rosters of experts will be informed, by lived experiences, subject matter knowledge and/or expertise in anti-Black racism and policing.

- Promoting consensus building. This approach is designed to enhance and promote collaborative solutions, involving communities, the OHRC, the TPS and the TPSB, wherever possible generally and specifically, to issues respecting anti-Black racism.

- In order to address issues with respect to implementation the OHRC further recommends:

- Creating an independent monitoring and evaluation system for the implementation of the recommendations that involves an effective and expeditious legally binding enforcement measure.

Data collection

From adopting a specific policy on race-based data collection, to collecting data on use-of-force reports, strip searches, charges, arrests, releases, and youth diversions, the TPS and TPSB have taken significant steps in data collection, as detailed in Chapter 9. There are, however, gaps that need attention.

For data collection to address systemic racism, the data must enable robust analysis of the full range of police–civilian interactions, identify racial disparities, and provide findings that can be decisively acted on.

As discussed in this report, gaps in the current policy remain and include:

- data collection on pedestrian stops occur only if the stop results in a written warning, ticket or arrest

- use of force that does not require medical attention (lower-level use of force)

- Phase 2 of the data collection strategy, which does not include all stops, including investigative detentions, protective searches (formerly Level 1 searches), and frisk searches

- data on intersecting Code grounds such as race and mental health.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB amend its Race-Based Data Collection, Analysis and Public Reporting Policy (RBDC Policy) to direct the TPS to collect, analyze and publicly release human rights-based data on an annual basis on the full range of police–civilian interactions, including stop and search activities, traffic and pedestrian stops, charges, arrests, releases, and use of force (including lower-level use of force).27

- The TPSB consider the OHRC’s methodology in A Disparate Impact, A Collective Impact and Dr. Wortley’s report, Racial profiling and the Toronto Police Service: Evidence, consequences and policy options, in developing its data collection and analysis.28

- Where the data reveals notable29 race-based disparities in service delivery, the TPS take immediate steps to inform the TPSB and enact an action plan to eliminate the disparity within a set timeline.30 The TPSB should require the TPS to publicly report on the steps taken to address the disparity.

- The TPS regularly evaluate officers on the extent to which they fill out all required data fields.

- The TPS work with external experts to develop procedures for auditing the accuracy of race reported by officers in documents such as Use of Force Reports and officers’ notes, verifying them against other sources of information that identify the subject’s race, e.g., body-worn camera images, driver’s licence photos, or civilian self-reported racial identity.

Stop and search incidents (including all traffic and pedestrian stops)

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS collect data related to stop and question incidents. The OHRC recommends that the data collected be consistent with recommendations 21 and 22 on stop and search in the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement.31

Charge, arrest, and release

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS collect and publicly report on data related to all charge, arrest, and release decisions. This should include demographic data about the person (race, Indigenous ancestry, age, gender, presence of a mental health disability), factors related to the decision to detain or release an individual, and information on decisions not to charge a person, such as the use of diversion programs. The TPS should review Dr. Wortley’s report on Racial Disparity in Arrests and Charges: An analysis of arrest and charge data from the Toronto Police Service (2020), and include relevant missing data that was flagged.

- The TPS track and report disaggregated data on the number of charges that are diverted from the court system.

Use of force

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS collect data on all use-of-force incidents, including lower-level use-of-force incidents where a civilian is not injured, or where physical force is used that does not require medical attention. The collected data

should be consistent with recommendation 31 regarding use of force in the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement.32

Data and performance management

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB amend its Race-Based Data Collection, Analysis and Public Reporting Policy to remove the prohibition on the use of race-based data in performance management, and direct the TPS to use the data collected when evaluating officer performance.

- Supervisory reviews of use-of-force incidents be connected to officer performance reviews. In this regard the OHRC adopts the jury’s recommendation on this subject from the inquest into the death of Jermaine Carby.33

Detention

The OHRC recommends that:

- Based on the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R v. Le, and its findings with respect to psychological aspects of encounters with police, the TPS collect race-based data on the number of persons who have been detained by police.

Data privacy

Privacy considerations for race-based data are always important. This is especially true for data collected in the absence of any regulatory framework, as was the case with street check data for several years leading up to 2017. Further, as noted in this report, the TPS and TPSB failed to purge historical street check data, much of which is the product of racial profiling.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB consult with the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (IPC) to develop appropriate privacy guidelines for the collection, analysis, and public release of the human rights-based data described above.

- TPS destroy personally identifiable information from carding/street check data collected before January 1, 2017, subject to any active court orders that may require the retention of the personal information in the data.

Early intervention systems (EIS)

Early intervention systems (EIS), also known as early warning systems, capture race-based data to alert supervisors to potential performance issues and misconduct concerns. In addition, these systems offer “resources and tools in order to prevent disciplinary action, and to promote officer safety, satisfaction and wellness.”34

The EIS should receive and integrate member information to identify any patterns of behaviour or incidents that are indicative of at-risk behaviour. In addition, the information captured by the EIS should assist with the regular supervision of members.35 The EIS may also be used to track indicators of officer wellness and prevent harm to officers and members of the public.

EIS typically have remedial objectives and as such, the output from these systems are not intended to trigger disciplinary measures. Nonetheless, there are opportunities for police services to use information from an EIS to inform the eventual imposition of discipline if necessary.

Recognizing that the indicators of racial discrimination may vary by police officer, platoon, unit or division, the range of relevant data points is specified below.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS EIS track indicators of racial discrimination or racial profiling by individual officers and platoons/units/divisions.

- The TPS build on its existing EIS to capture all necessary information to alert supervisors to individual and platoon/unit/division conduct for potential racial discrimination that needs to be addressed.

This system should capture data and flag patterns related to racial disproportionalities and disparities36 in the areas identified in:

- the OHRC’s Inquiry report

- TPSB’s policy on Race-Based Data Collection, Analysis and Reporting

- negative findings in HRTO and court decisions where racial discrimination is at issue, and

- Charter violations.

- The TPS ensure that the EIS captures the information outlined in the recommendation 35 and 36 for EIS in the OHRC’s Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement.37

- The TPS use the EIS in performance management and progressive remedial action, consistent with labour relations requirements, by:

- Establishing and implementing EIS performance indicators, including through internal benchmarking, that will trigger supervisory review and referrals to Professional Standards.

- Developing EIS indicators for supervisors based on the EIS performance of their unit.

- Maintaining data on each officer’s use of force, including each discharge of a firearm or CEW, and tracking this against established benchmarking.38

- Requiring command staff and other supervisors to regularly review EIS data to evaluate performance of all officers.

- Requiring that remedial action be considered when an officer is flagged based on EIS performance indicators or audits of officers’ body-worn and in-car camera recordings. Remedial action includes but is not limited to additional training and education, reassignment, counselling, heightened monitoring, and heightened supervision.

- The remedial approach should include progressive performance management where appropriate.39

- The Chief of Police should report to the TPSB on the remedial or disciplinary measures used on officers based on, among other factors, EIS data on racial discrimination, subject to the confidentiality provisions of the Police Services Act.40

- Positive conduct by an officer included in a supervisor’s review should be recognized.

- When remedial efforts have not successfully addressed concerns about a pattern of racial disparity in an individual officer’s activities, supervisors should consider if it is appropriate to refer the officer’s conduct to Professional Standards.

- Establishing and implementing EIS performance indicators, including through internal benchmarking, that will trigger supervisory review and referrals to Professional Standards.

- The Chief of Police require supervisors to thoroughly review and document use-of-force incidents immediately after the incident occurs to determine if there were credible non-discriminatory explanations for use of force. This is subject to the jurisdiction of the Special Investigations Unit.

- Where supervisors do not identify a credible non-discriminatory explanation, the officer’s conduct and supervisor’s concerns should be flagged in the EIS and referred to Professional Standards for a full investigation.

Body-worn cameras

The TPSB and TPS consulted the OHRC on body-worn cameras (BWCs) to inform the development of the TPSB policy and TPS procedure in Fall 2020. In addition, the OHRC made written submissions setting out concerns with BWCs.41 In light of the TPS and TPSB’s decision to move forward with the implementation of BWCs, the OHRC recommends the following policy guidelines:

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB amend its policy on body-worn cameras (BWC) to:

- Specify the frequency of reviews and require public reporting on them.

- Create a process whereby community advisory groups can review, on a random basis, body-worn and in-car camera recordings to assess if officers are providing a service environment free from racial discrimination. This process is similar to that adopted by the Independent Scrutiny of Police Powers Panel in Avon and Somerset England.42 Such a process should ensure that reviews do not interfere with ongoing investigations or legal proceedings.

- Require public reporting on the quantity and quality of supervisors’ audits related to discrimination every year. In this reporting, identify how many instances of potential racial bias were identified, how many internal conduct complaints were initiated based on reviewing BWC footage, and the nature of any remediation or discipline of individual officers that followed. The recommendation builds upon the TPSB’s recommendation that

supervisors regularly review recordings for implicit or explicit discrimination.

- The TPSB direct the Chief of Police to amend procedures on the use of BWCs in line with the preceding policy prescriptions.

Officer accountability

As employers, it is important to fully investigate complaints related to discrimination. Organizations should have a clear, fair and effective mechanism for receiving, investigating. and resolving complaints of discrimination, and to ensure that human rights concerns are brought effectively to the attention of the organization.

During the Inquiry, the OHRC identified a lack of effective monitoring and accountability for anti-Black racism and racial discrimination of Black people by the TPS and TPSB. To address this concern, the Chief of Police must broadly exercise their discretion to investigate and address potential instances of misconduct in a fair and transparent way. The TPSB must review the administration of complaints and establish appropriate disciplinary guidelines.

Monitoring and investigations

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB enact a policy that requires the Chief of Police to confirm that the following steps are taken:43

- On providing notice to the subject officer, proactively investigate the race of the alleged victim of the misconduct, potential racial profiling or discrimination against Black individuals, even where claims of racial profiling or discrimination are not explicitly raised by a complainant, witness, SIU Director, OIPRD,44 LECA, or any legal decision involving a Charter breach by the TPS.

- Investigate all concerns about officer misconduct raised by the SIU Director in letters to the Chief of Police, and conduct a full investigation into all issues raised.

- Automatically initiate a Chief’s complaint investigation (if an investigation has not already been undertaken) when findings or comments in decisions of courts or tribunals, correspondence from the OIPRD, LECA, SIU Director, or any legal decision involving a Charter breach by the TPS that reflect conduct potentially consistent with anti-Black racism, racial profiling, or discrimination.

- Implement a duty to report procedure, which calls on officers to self-report negative findings about their testimony, or conduct in decisions of courts or tribunals, correspondence from the OIPRD, LECA, SIU Director, or any legal decision involving a Charter breach.

- Where officers report these findings, a Chief’s complaint investigation should be initiated.

- Establish a process within the Service to search and track negative findings about an officer’s testimony or conduct in decisions of courts or tribunals, correspondence from the OIPRD, LECA, SIU Director, or any legal decision involving a Charter breach that reflects conduct consistent with anti-Black racism, racial profiling, or discrimination. This process should help supervisors review these concerns in one centralized location.

- Track individual findings and trends and hold officers accountable for such conduct using appropriate remedial or disciplinary measures.45

- Require that all Professional Standards investigators are trained to identify violations of the Human Rights Code, including potential racial profiling or discrimination.

- Direct the Chief of Police to develop a procedure to monitor all Charter breaches that reflects conduct consistent with anti-Black racism, racial profiling, or discrimination committed by TPS officers, and report these decisions on an annual basis at a public board meeting.46

Complaints administration

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB establish policies to:

- Review and publicly report annually on the Chief of Police’s administration of:

- Internal complaints, officer’s testimony or conduct in decisions of courts or tribunals, correspondence from the OIPRD, LECA, SIU Director, or any legal decision involving a Charter breach that reflects conduct consistent with anti- Black racism, racial profiling, or discrimination, and when officer conduct is consistent with racial profiling or racial discrimination.

- Administrative investigations (formerly called Section 11 reports).47

- Request and review decision letters from the SIU Director to the Chief of Police. The TPS Special Investigations Unit Procedure (13-16) should be amended to direct the TPS to include a copy of the SIU Director’s Letter to the Chief of Police with the administrative investigation when it is sent to the TPSB.

- Direct the Chief of Police to develop a procedure that sets out the steps to be followed when the Crown Attorney’s Office reports that an officer has been dishonest as a witness, or where a court, tribunal, or complaint body finds that the officer engaged in racial discrimination.

- Review and publicly report annually on the Chief of Police’s administration of:

Performance management

The OHRC recommends that:

- The Chief of Police require that performance management includes:

- For officers:

- A written assessment of whether officers violated any procedures including those related to body-worn cameras.

- An evaluation of how accurately the officer reports use-of- force incidents.

- An evaluation of how well officers grasp and implement training on racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti- Black racism,48 including how well officers de-escalate situations49 and identify appropriate levels of force to use.50 This evaluation should also consider any tribunal or court findings of discrimination or other behaviour that contravenes the Code or the Charter.

- For supervisors:

- An assessment of whether use-of-force incidents and body-worn camera footage were adequately reviewed, and whether misconduct by officers is met with appropriate corrective and disciplinary action.

- For officers:

Performance reviews

The performance review process must actively address systemic discrimination in police services. Motivating police practices that will generate better outcomes should be a key objective of the review process.

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPS revise the process for performance reviews to:

- Establish an explicit requirement that interactions with people in crisis be considered.

- Place a greater emphasis on de-escalation skills such as communication, empathy, proper use of force, and use of specialty teams where required.

- Utilize an officer’s use-of-force reports when assessing training needs and suitability for particular job assignments to the extent possible subject to any restrictions created by Reg. 926/90.51

- Consider creating incentives for using alternative measures that divert charges from the criminal court system.

Accountability

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB establish policies that set out circumstances where the Chief of Police should consider discipline, up to and including dismissal, when officers’ behaviour is found to be consistent with racial discrimination, in accordance with the established disciplinary process

- The TPS and the TPSB consider officer behaviour found by a court or tribunal to be consistent with racial discrimination and substantiated by internal investigations as a negative factor in promotion decisions.

- The TPS develop a mechanism for officers to report discrimination that protects the confidentiality of the reporting officer, subject to any legal restrictions.52

- The TPS take proactive steps to ensure that officers who initiate complaints against other members are not subject to reprisal. These steps may include assessing the workplace climate and following up with the complainant.

TPS/TPSB use of inquest recommendations

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB conduct a comparative analysis of recommendations from the Jardine-Douglas, Klibingaitis and Eligon (JKE) inquest and Loku inquest to identify any gaps in implementing the JKE recommendations, and:

- Determine why some inquest recommendations continually appear as areas of concern.

- Work with an independent expert and ARAP to fully assess the implementation of the recommendations from these and other similar inquests.

- Demonstrate they have meaningfully consulted on this analysis with Black communities.

- The TPSB develop a policy that sets out the steps for receiving, implementing and publicly reporting on all recommendations from coroner’s inquests directed to the TPS or TPSB, or recommendations directed to all police services in Ontario.

Transparency

The OHRC recommends that:

- The TPSB establish a policy that directs the Chief of Police to provide the TPSB annually with all instances of racial profiling and racial discrimination found to be committed by police officers through decisions of the HRTO, the TPS Disciplinary Tribunal, courts and other tribunals, along with details of what corrective or disciplinary actions were taken in response, subject to the confidentiality provisions of the Police Services Act (PSA).53

This information should also be publicly released annually in a manner that is consistent with the confidentiality provisions of the PSA and any subsequent legislation such as the Comprehensive Ontario Police Services Act (COPSA).

- The TPSB develop a policy on the public release of aggregated information about officer activities, and that this information be released in a way that enables the public to understand how officers allocate their time, including a breakdown of the time spent responding to calls, engaging in proactive investigations, and traffic enforcement.54

- The TPSB develop a policy on the annual public release of information about the calls for service it receives, and that this information be released in a way that enables the public to understand how many calls for service are related to social issues such as mental health, addictions, homelessness or other non-criminal matters.

The TPS should also release information about the nature of the response provided by the police service55 and the amount of time required to address the call.

Multi-year action plan

The OHRC recommends that:

- To successfully implement these recommendations, the TPS create and publish a multi-year action plan that incorporates the OHRC’s recommendations from this Inquiry report, From Impact to Action, with timelines to implement all recommendations.

- The TPS and TPSB consult with the ARAP and CABR to establish this action plan before final approval by the OHRC.

Recommendations relevant to the Province of Ontario

The OHRC recognizes that Ontario fulfills an essential role in establishing the legislative and regulatory framework which governs police services and that the TPS and TPSB operate in, and the TPS and TPSB may not have jurisdiction in some instances to enact necessary change without the assistance of the provincial government.

To borrow the words of the Auditor General’s conclusion, a whole-of- government and whole-of-community approach is needed to address many of the issues that police respond to, and investment in social service infrastructure and alternative strategies is required.56 In addition, these recommendations can impact other police services across Ontario.

Stop and search – restricting officers’ discretion to approach individuals in non-arrest scenarios

While O. Reg. 58/16: Collection of Identifying Information in Certain Circumstances has banned arbitrary stops, as discussed in Chapter 6 of this report, the OHRC continues to have significant concerns about unjust stops.57

The OHRC recommends that the TPSB urge the Province of Ontario to:

- Develop and implement criteria that narrow the circumstances where officers can approach or stop a person in a non-arrest scenario, and create a framework for rights notification that is consistent with the OHRC’s Submissions to the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services as part of its Strategy for a Safer Ontario.58 These criteria are more stringent than the criteria mandated by the Province in O. Reg. 58/16.

Charges

The OHRC recommends that the TPSB urge the Province of Ontario to:

- Implement Crown pre-charge approval before laying a criminal charge.

- Ensure that assistant Crown attorneys are trained on the historical barriers faced by Black communities, the presence of systemic racial discrimination in the criminal justice systems, and alternatives to charges that can be used in appropriate circumstances.

- Expand initiatives that create alternatives to charges such as judicial referral hearings, community justice centres, and embedded Crown counsel.

Use of force

The OHRC recommends that the TPSB urge the Province of Ontario to:

- Review the use-of-force weapons provided to front-line officers and consider whether there are situations province-wide where officers can be deployed with non-lethal weapons, instead of lethal use-of-force options such as firearms.

- Evaluate the Public-Police Interactions Training Aid in consultation with, experts and Code protected groups including Indigenous and Black communities and persons living with mental health or addition issues. This evaluation should assess whether the introduction of the Training Aid in 2023, has helped to reduce use of force rates for Indigenous and Black communities. This assessment should consider data on police use of force collected pursuant to the Anti-Racism Act.

The findings from this evaluation should be used to develop leading practices that are used to update the Training Aid.

Data collection

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Require police services province-wide to collect data in a manner consistent with these recommendations, requirements established by the Anti-Racism Act, and the objectives of the Human Rights Code, as part of the TPSB’s ongoing engagement with the province on use of force.

- Mandate province-wide race-based data collection, analysis, and reporting across the spectrum of officer activities, including stop and search practices, charges and arrests, and use of force.

Early intervention systems (EIS)

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Mandate the implementation of early intervention systems consistent with these recommendations provincewide.61

Artificial intelligence

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Establish legislation and regulations to govern the development, use, implementation, and oversight of artificial intelligence in policing consistent with the OHRC’s Submission on TPSB Use of Artificial Intelligence Technologies Policy (i).62

Policing standards

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Develop standardized key performance indicators and assessment models related to efforts to address anti-Black racism in policing. These standards should be informed by consultations with the OHRC, the Anti-Racism Directorate, and input from Indigenous, Black, and other racialized communities across the province.

Performance management

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Amend the Police Services Act and/or the Community Safety and Policing Act, 2019,63 to include greater transparency on police discipline.

For example, there should be public reporting on cases that are addressed through informal discipline.64

a) Amend restrictions in Reg 926/90 that prevent use of force reports from being used to address the full range of officer performance issues.

- Amend the police as a witness section of the Crown Prosecution manual to address findings of racial discrimination, racial profiling and anti-Black racism made against officers.

Where the Prosecutor becomes aware of credible and reliable information that an officer has been found to have engaged in racial discrimination and/or racial profiling, or a Charter breach that reflects conduct consistent with racial discrimination and/or racial profiling, the Prosecutor should direct the matter to the Crown attorney, who will in turn notify the Chief of Police.

Comprehensive Ontario Police Services Act (COPSA)

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Develop regulations in the COPSA that will set out circumstances where termination or suspension without pay should be considered, including instances where a court or tribunal or disciplinary proceeding finds that an officer has engaged in serious misconduct.

The COPSA should include specific reference to misconduct related to racial discrimination or anti-Black racism as considerations when assessing whether to terminate or suspend without pay.65

Reducing the scope of policing activities

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario:

- Publicly review civilianizing non-emergency police functions provincewide.66

- Amend section 17 of the Mental Health Act to facilitate non-police responses to issues related to mental health, substance use.67

The OHRC recommends that the Province of Ontario work with the TPS and TPSB to assist them in:

- Renewing efforts to achieve their goal of making the mobile crisis team available 24 hours/7 days a week, as stated in the 81 recommendations arising from the Police Reform Report.

Specifically, the OHRC encourages the TPS and TPSB to further engage Ontario’s Ministry of Health to achieve 24-hour MCIT coverage across Toronto.

The OHRC recommends that:

- Funding requests made by the TPSB and TSP pursuant to recommendations68 from the Auditor General’s report A Journey of Change: Improving Community Safety and Well-Being Outcomes explicitly request funding to address the well-being of Black communities, and other Code-protected groups that have been disproportionately burdened by police interactions as documented in this Inquiry.

Special Investigation Unit investigations

Pursuant to section 11 of O. Reg. 267/10 under the Police Services Act, municipal police chiefs are required to investigate any incident with respect to which the Special Investigation Unit SIU has been notified, subject to the SIU’s lead role in investigating the incident. Chiefs are also required to produce a copy of their investigative report to their police services board. Boards have the discretion to make these reports public.

The OHRC recommends that:

- Reports by Chiefs of Police related to investigations of incidents where the SIU has been notified under section 11 of O. Reg. 267/10 of the Police Services Act, must be routinely disclosed to the public, subject to the confidentiality provisions of the PSA.69

Recommendations to the Special Investigations Unit

A Collective Impact, the OHRC’s first Inquiry report, included analysis of data obtained by the OHRC from the Special Investigations Unit (SIU). In addition, the OHRC met with Director Joseph Martino.

Through this work, several recommendations flowed directly to the TPS and TPSB.

The OHRC recommends that the SIU:

- As part of its analysis of its race-based data from 2020 onwards, continue to monitor whether there are racial disparities in the charge rate, and take steps to address them if they occur. The SIU should consider the OHRC’s analysis in A Collective Impact in this analysis.

- Require that all investigators receive training and education on how to identify anti-Black racial discrimination during their investigations. The training should occur on a regular basis and address direct and indirect forms of racial discrimination or unconscious bias.

Appendix 1 Endnotes

1 Report of the Independent Civilian Review into Missing Person Investigations https://www.tps.ca/chief/chiefs-office/missing- and-missed-implementation/report-independent-civilian-review-missing-person-investigations/

2 Missing and Missed: Report of the Independent Civilian Review into Missing Person Investigations, vol III (Toronto Police Services Board, 2021) at 694, online (pdf): The Honourable Gloria J. Epstein, Independent Reviewer

<https://www.tps.ca/media/filer_public/34/ba/34ba7397-cbae-4f44-8832-cd9cb4c423ca/71ed3bb5-65a5-410e-a82f- 3d10f58d0311.pdf>

3 A KPMG audit of the TPS advanced civilianizing as a way to respond to demands placed on the service. The audit recommends the following: “Conduct service-wide review of all positions, job descriptions and performance expectations within TPS against business requirements and the need to maintain a critical mass of sworn capability. This will determine which positions require uniform skills and/or are a core police service in order to highlight roles to be considered for civilianization, with default outcome to outsource if option is determined to be more cost-efficient and achieve a better outcome than the status quo.” In addition, KPMG’s review notes that other large cities have civilianized services formally performed by police. For example:

- City Auditor in San Jose, CA: recommended that San Jose PD consider civilianizing some investigative duties and cold case roles.

- San Francisco Police: hired 16 civilians to focus on property crimes, freeing up uniformed officers for other critical crimes, resulting in salary differential of up to $40,000 per person.

- Durham, UK: civilian volunteers are used to assist police officers in canvassing neighbourhoods after violent crimes, patrolling shopping centres during busy holiday seasons and conducting property checks for vacationers.

- Edmonton and Waterloo Regional Police use mixed civilian and sworn teams for crime scene and criminal investigation.

See Toronto Police Services Board, Opportunities for the Future for the Board’s Consideration (December 2015) online (pdf): www.tpsb.ca/KPMG%20-%20Comprehensive%20Organization%20Review%20-

%20Potential%20Opportunities%20for%20the%20Future%20Report%20to%20the%20TPSB%20(FINAL)%2017Dec%202015.pdf. TPS’s has implemented the following programs which civilianize core services: 911 Call Diversion Project: TPS and the Gerstein Crisis Centre, a civilian based organization, will work, “collaboratively, but distinctly, to assist in the diversion of non-emergency mental health related calls away from a police response.” This pilot program was created in response to the 81 recommendations in the Police Reform Report. (See: Toronto Police Services, 9-1-1 Call Diversion Project (November 2021) https://www.tps.ca/media-centre/stories/9-1-1-call-diversion-project/.) Traffic Agent Program: According to the Highway Traffic Act, only police officers are allowed to direct traffic at signalized intersections. In response TPS worked with the City of Toronto to have traffic agents appointed as special constables though the Traffic Agent Program. Traffic Agents have the authority to manage traffic at all intersections in Toronto in place of the paid duty officers. (See: City of Toronto, Traffic Agent Program, https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/streets-parking- transportation/traffic-management/traffic-agent-program/). TPS has also created a District Special Constable position that can be responsible for transportation of detainees and apprehended persons, report taking. The OHRC acknowledges the TBSB’s Letter of January 20, 2021, to the Federal Ministry of Health, the Provincial Ministry of Health, and the City of Toronto, expressing the Board's request for additional, sustained investment for community-based mental health and addictions services in Toronto. The letter responds to recommendation 11 in the Police Reform Report.

4 This includes the Toronto Community Crisis Service (TCCS) launched by the City of Toronto. See: https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/public-safety-alerts/community-safety-programs/toronto-community-crisis- service/

5 Ontario Human Rights Commission, Strategy for a Safer Ontario – Submission to the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (29 April, 2016) online: <Strategy for a Safer Ontario – OHRC submission to MCSCS | Ontario Human Rights Commission>.

6 Toronto Police Service: Race-Based Data Collection Strategy, Use of Force: Measurement & Outcomes RBDC Video 4 Transcript, https://www.tps.ca/media/filer_public/b9/f4/b9f492b5-8e11-450a-af6e-deae2658010b/1ec05b46-427f-41eb-8697- cd12e95dad0b.pdf

7 African Canadian Legal Clinic, Civil and Political Wrongs: The Growing Gap Between International Civil and Political Rights and African Canadian Life (June 2015) at 12, online (pdf): <(rmozone.com)> “In the past, stereotypes of Black people were used to justify slavery and segregation. Today they provide the basis for discriminatory policies and practices that violate the civil and political rights of African Canadians. These include the over-policing of African Canadian communities, police brutality, disparities in sentencing and policing accountability institutions absolving law enforcement agencies of wrong-doing when the victim is African Canadian.”

7 The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing underscored the importance of exploring alternatives to charges in their recommendations. Recommendation 2.2.1 states: “Law enforcement agency policies for training on use of force should emphasize de-escalation and alternatives to arrest or summons in situations where appropriate.” See: President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, (May 2015) at 20, online (pdf): (usdoj.gov); some precincts in and around Seattle have implemented a pre-booking diversion strategy; also see the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program. The program gives police officers the option of transferring people arrested on drug and prostitution charges to social services rather than sending them deeper into the criminal justice system. National Institute of Corrections, Jail Alternatives (U.S. Department of Justice) online:<https://nicic.gov/tags/jail-alternatives>. Police discretion in Toronto is very much applied to charge/no charge decisions. It is common for the TPS to clear incidents without issuing charges. For example, in 2019, 21.4% of cleared Criminal Code incidents (excluding traffic) in Toronto (9,043 out of 42,221) were “cleared otherwise.” Statistics Canada, Table: 35-10-0180-01: Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, police services in Ontario, (29 July 2013), online: <https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510018001>

As the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics explains: “There are instances where police may clear (or solve) an incident, but do not lay criminal charges or recommend such charges to the Crown. For an incident to be 'cleared otherwise,' the incident must meet two criteria: 1) there must be at least one charged/suspect chargeable (CSC) identified, and 2) there must be sufficient evidence to lay a charge in connection with the incident but the person identified is processed by other means,” Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Revising the classification of founded and unfounded criminal incidents in the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Catalogue No. 85-002-X (Statistics Canada, 12 July 2013) at 7, online (pdf): <https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54973-eng.pdf>. Cleared otherwise decisions can be made for a variety of reasons, including “departmental discretion” (ibid. 5, Figure 1). This recommendation rests on the proposition that this discretion should be exercised in a way that counteracts current patterns of race-specific over-charging by the TPS.

8 Ontario Human Rights Commission, Submission on Ontario’s Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI) Framework (June 2021) online: (ohrc.on.ca)

9 Ontario Human Rights Commission, Submission on TPSB Use of Artificial Intelligence Technologies Policy (September 2021) online: Submission on TPSB Use of Artificial Intelligence Technologies Policy | Ontario Human Rights Commission (ohrc.on.ca) 10 Ontario Human Rights Commission, Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement (Government of Ontario, 2019) at section 4.2.6. Artificial intelligence, online (pdf): Eliminating Racial Profiling in Law Enforcement (ohrc.on.ca) which outlines why these dimensions of predictive policing may feed, or do feed, into racially discriminatory policing.

11 ”The OHRC holds the view that FR [facial recognition] is not appropriately regulated under existing law... Yuan Stevens of Ryerson University and Sonja Solomun of McGill University have observed: In Canada, it is currently possible to collect and share facial images for identification purposes without consent, and without adequate legal procedures, including the right to![]() challenge decisions made with this technology.” See: Ontario Human Rights Commission, OHRC comments on IPC draft privacy guidance on facial recognition for police agencies, (November 19, 2021) online <https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/news_centre/ohrc- comments-ipc-draft-privacy-guidance-facial-recognition-police-agencies>; Also see: Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Privacy Guidance on Facial recognition for Police Agencies (May 2022) online: <https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy- topics/surveillance/police-and-public-safety/gd_fr_202205/> Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial privacy commissioners are of the opinion that the current legislative context for police use of FR is insufficient. In the absence of a comprehensive legal framework, there remains significant uncertainty about the circumstances in which FR use by police is lawful.”

challenge decisions made with this technology.” See: Ontario Human Rights Commission, OHRC comments on IPC draft privacy guidance on facial recognition for police agencies, (November 19, 2021) online <https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/news_centre/ohrc- comments-ipc-draft-privacy-guidance-facial-recognition-police-agencies>; Also see: Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Privacy Guidance on Facial recognition for Police Agencies (May 2022) online: <https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy- topics/surveillance/police-and-public-safety/gd_fr_202205/> Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial privacy commissioners are of the opinion that the current legislative context for police use of FR is insufficient. In the absence of a comprehensive legal framework, there remains significant uncertainty about the circumstances in which FR use by police is lawful.”

- In October 2022, The Global Privacy Assembly, Resolution on Principles and Expectations for the Appropriate Use of Personal Information in Facial Recognition Technology called for, ““...clear and effective accountability mechanisms”, including “clear governance and risk mitigation policies for all uses of facial recognition.”

12 Ontario Human Rights Commission, Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement (2019) at 4.2.6. Artificial intelligence 46–49, online (pdf): Eliminating Racial Profiling in Law Enforcement (ohrc.on.ca)